Specs Fine Books

1777 CHANCE BRADSTREET. Important American Revolutionary Slave Document. Exhibited at The Smithsonian!

1777 CHANCE BRADSTREET. Important American Revolutionary Slave Document. Exhibited at The Smithsonian!

Couldn't load pickup availability

An opportunity to purchase a very important document exhibited at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

For a fuller history of the document, Chance Bradstreet, and his important American Patriot "owners," see this article in The Smithsonian.

What's remarkable, is that all we know about Chance has emerged by scholarly excavation over just the last few decades. In an article by Katie Nodjimbadem of the Smithsonian, she details the important arc of Bradstreet as emblematic of the story of so many unnamed Massachusetts slaves who watched their owners fight for liberty, only to be denied their own. Then, after the grind of time to emerge as full participants in a post-abolition New England.

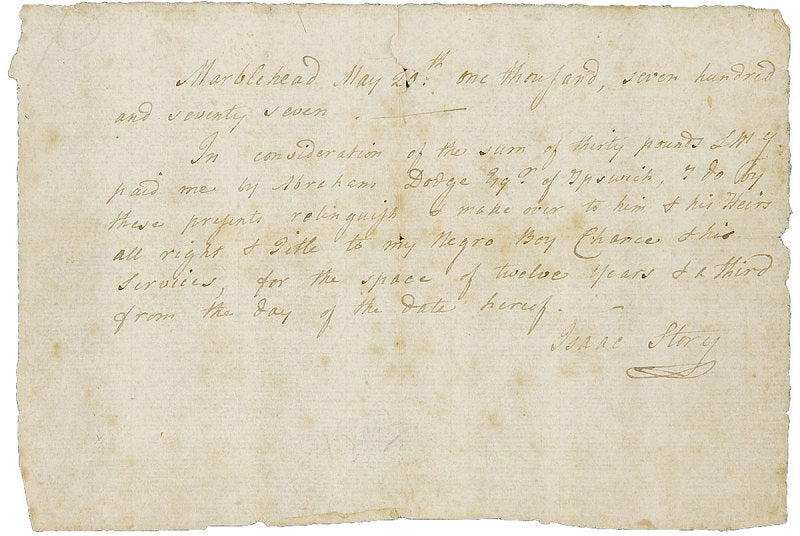

At our documents date, 1777, the American Revolution was in full swing and talk of liberty was ever present in Massachusetts. The enslaved listened. That year, Reverend Isaac Story of Marblehead, Massachusetts, leased his 14-year-old slave to Abraham Dodge, a ship captain and maritime trader living in the neighboring town of Ipswich, about 30 miles north of Boston.

Named Chance Bradstreet, the enslaved adolescent lived with the Dodges at 16 Elm Street, a two-and-a half-story house, which Dodge purchased upon his return from fighting in the Revolutionary War. Two hundred years later, that same house now stands as the centerpiece in the exhibition “Within These Walls” at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. The present document was temporarily displayed as part of the exhibition by private loan.

Details of Chance Bradstreet's life have only recently come to light, largely in an effort to tell the story of the Ipswich home.

When the museum (then called the National Museum of History and Technology), acquired the house in 1963, as a result of efforts by Massachusetts locals to save the house from demolition, curators displayed it as a nod to the technology of the colonial era. But in 2001, the museum revamped the exhibition to tell the personal stories of five families who called it home over the course of two centuries. Abraham Dodge and Chance were part of the exhibition’s narrative.

But, as is common with the histories of enslaved people, information about Chance was lacking. In fact, initially the only evidence of his existence was found in Dodge’s will, in which the patriot noted that his wife, Bethaia, would inherit “all the right to the service of my negro man Chance.”

The more information emerged. In 2010, genealogist, Christopher Challender Child, visited the museum and became interested in the story of Chance, who was noted as a “mystery” in the museum’s caption panel. Child returned from his vacation focused on finding post-Revolutionary African-Americans named Chance in Massachusetts, and hoping to locate the identity of the young slave.

Child uncovered Chance’s birthday when he found a 1912 posting from the genealogy column in the Boston Evening Transcript, which referenced a book belonging to a woman named Sarah Bradstreet. According to the posting, "on the inside of the back cover is written: ‘Chance was born on the 16th of September, 1762.'"

Sarah Bradstreet was the daughter of the Reverend Simon Bradstreet of Marblehead, whose inventory lists “Negro Woman Phillis (presumably Chance’s mother)” and “Negro Boy Chance.” Sarah was married to Isaac Story, who inherited Phillis and Chance upon the reverend’s death, and later leased Chance to Dodge. The terms of the agreement under which Story relinquished Chance stated that the lease would last “12 years and a third.”

Then, the discovery of our document, an actual lease agreement document describing the arrangement above. It cemented the entire story together; a physical artifact fitting all the pieces into one clear narrative.

There was more information emerging as well. An entry in a 1787 account page from Bethaia, which Nickles discovered in a Massachusetts archive, notes that Chance worked 16 days “making fish,” or drying and preserving codfish to be shipped to Europe and to feed slaves in the West Indies.

Chance was enslaved all throughout the Revolution; though the 1780 ratified Massachusetts Constitution that stated, “All men are born free and equal; ”through the court cases of slave Quock Walker who sued on the basis of those articles for his own freedom; though Chief Justice William Cushing ruling in 1783 where he stated, “I think the idea of slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract.”

In spite of all these actions, change was slow. It was not until 1790 that slaves were no longer listed in the inventories in Massachusetts. It is likely that Chance continued in servitude to Bethaia, according to her husband’s will, until Abraham's death in 1786 as another document indicates that Chance was still enslaved after the court’s ruling.

It is likely that he did not gain his freedom until the expiration of this lease in 1789. Marblehead tax records from 1794 in Marblehead list him as a free man. A town valuation list from 1809 suggests that not only did Chance find freedom but he also built a life for himself. According to this record, which Childs discovered, a “Chance Broadstreet” was head of a two-person household on Darling Street. The other person’s identity is unknown, but it could have been his presumed mother, Phillis.

According to the death records, he died a free man in 1810.

Share