Specs Fine Books

1777 RARE REVOLUTIONARY WAR MANUAL. Provenance to the Son of One of the Heroes of the American Revolution.

1777 RARE REVOLUTIONARY WAR MANUAL. Provenance to the Son of One of the Heroes of the American Revolution.

Couldn't load pickup availability

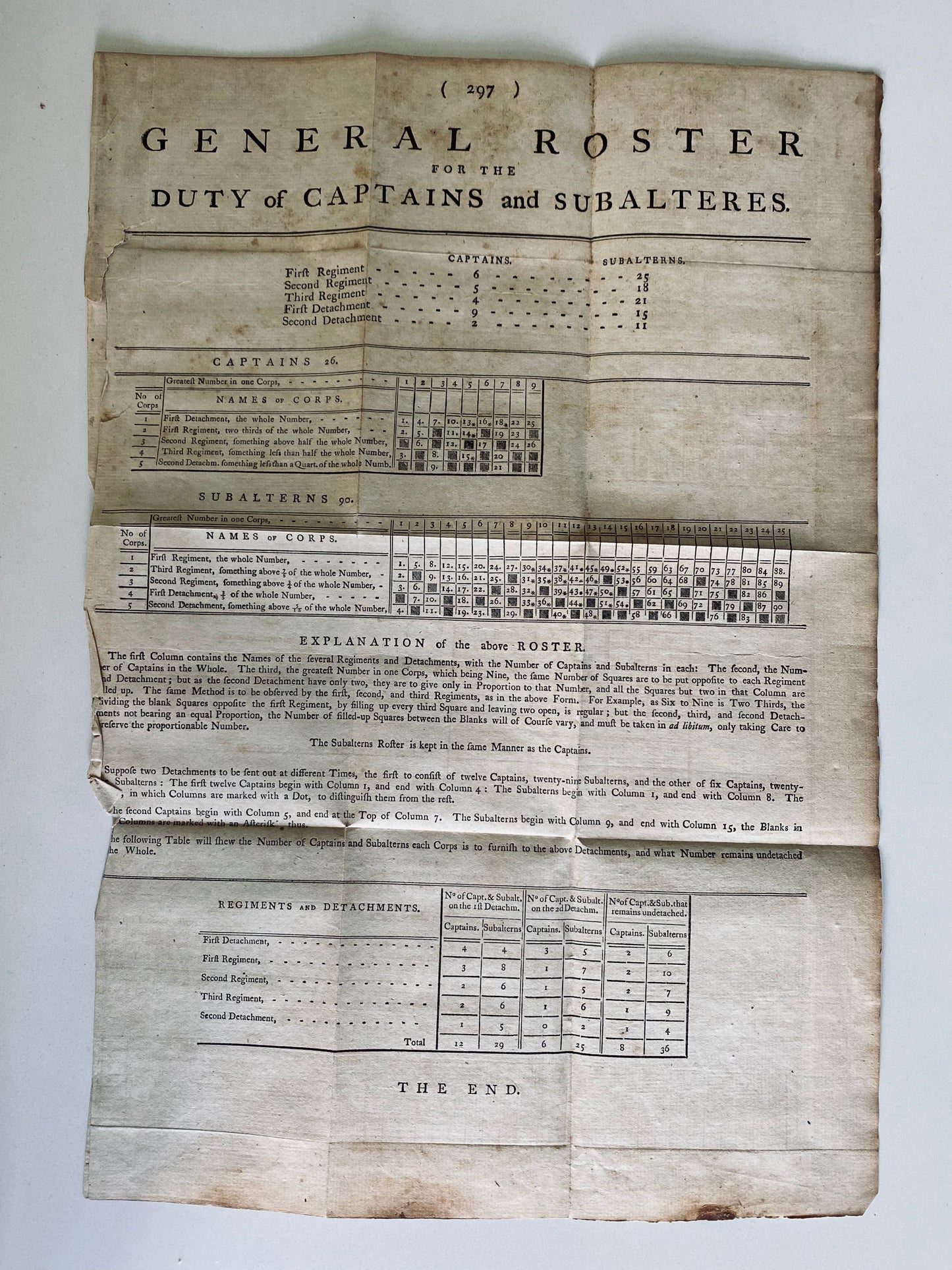

An exceptionally scarce item, with no others on the market, the present was issued by the British in 1777 as a sort of "carry with" manual of troop organization, camp organization, and military procedure for British officers during the American Revolution, and from that vantage alone it provides a significant glimpse into the War. Copies appear exceptionally rare on the market and we locate only a handful of institutional examples.

That said, the provenance on this rare survivor is decidedly American rather than British. Was it perhaps snatched up by an American officer, perhaps our Daniel Morgan [see below]?

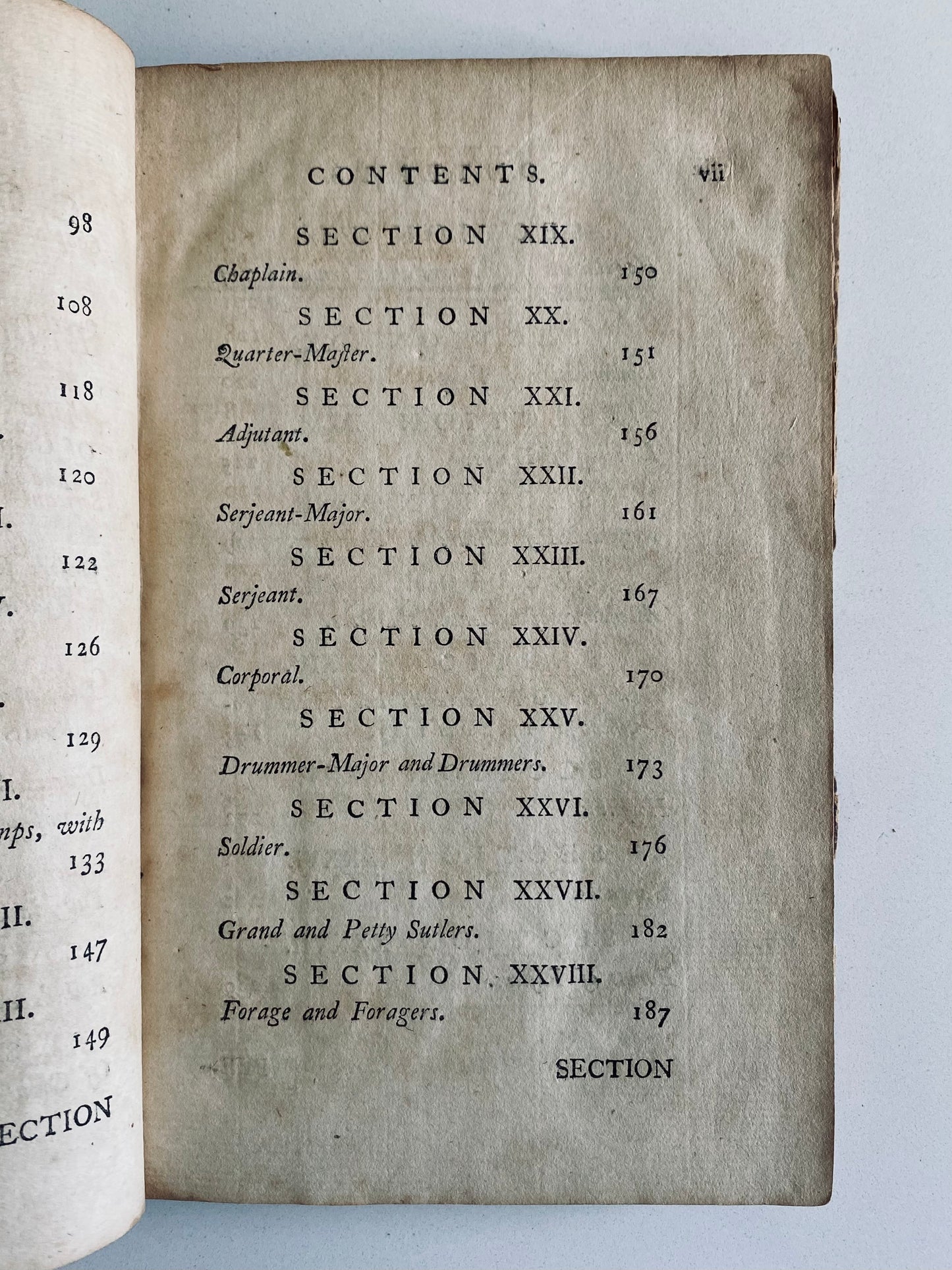

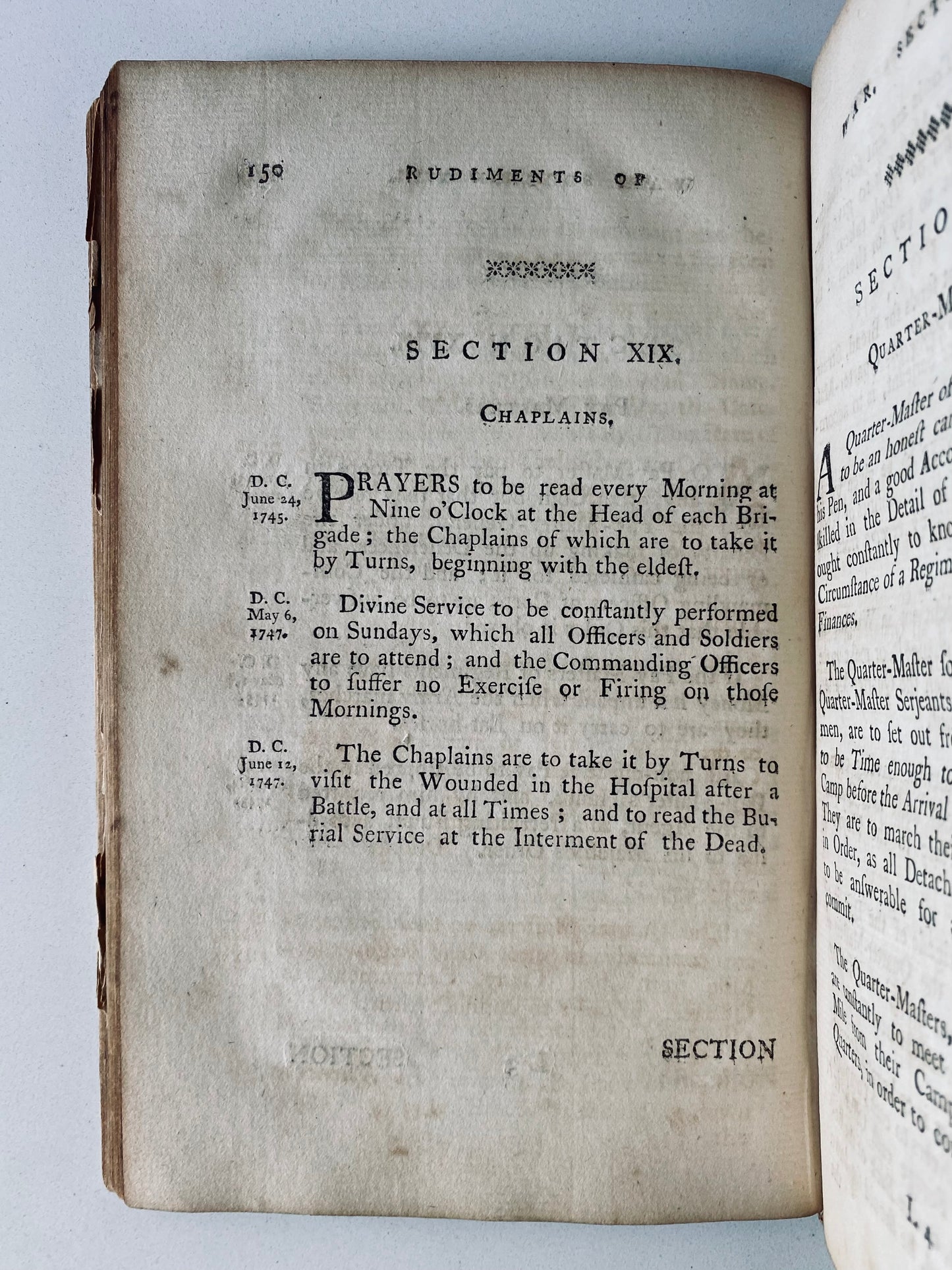

The Rudiments of War: Comprising the Principles of Military Duty, in a Series of Orders Issued by Commanders in the English Army. To which are added, Some other Military Regulations, for the Sake of Connecting the Former. London. Prined for N. Conant (Successor to Mr. Whiston], in Fleet Street. 1777. 297pp.

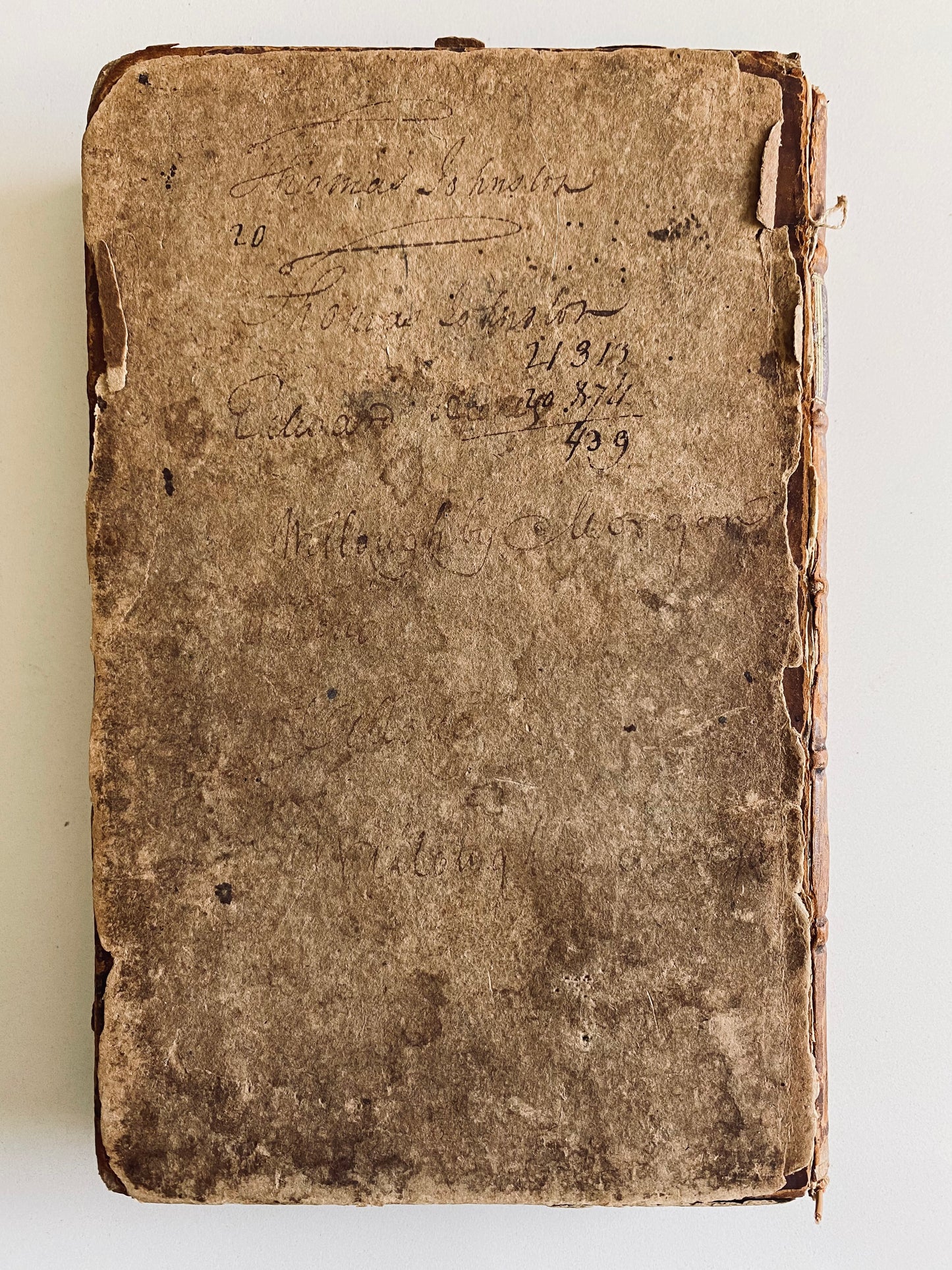

Both boards were early wrapped in brown paper and signed at least 7 separate times [perhaps at each promotion or new position] by the son of American Revolutionary War hero, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan [1736-1802], Willoughby Morgan

Brigadier General Daniel Morgan.

Daniel Morgan, an American hero during the American Revolution, grew up with a rebellious streak. As a young man, he settled in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley outside Winchester. Morgan worked as a teamster, hauling freight to the eastern part of the colony.

His teamster career drew him into the French and Indian War, during which he helped to supply the British Army. He soon became known as the “Old Wagoner.” He accompanied General Edward Braddock on his ill-fated campaign against the French and Indians at Fort Duquesne. During the expedition, Morgan annoyed a superior officer who struck him with the flat of his sword. Morgan knocked the man down. For his impertinence, Morgan was punished with 500 lashes—typically fatal number. He survived the ordeal, carrying his scars and his disdain for the rest of his life. Afterward, when Morgan retold the story, he commonly boasted that the British had miscounted, only giving him 499.

Morgan eventually joined a company of rangers in the Shenandoah Valley. Outside Fort Edward, Morgan and his companion were ambushed by Indians allied with the French. Morgan took a musket ball through the back of his neck that crushed his left jaw and exited his cheek, taking all his teeth on that side of his mouth. He miraculously survived the encounter but carried the scars with him for the rest of his life.

After the outbreak of the American Revolution, Morgan led a force of riflemen to reinforce the patriots laying siege to Boston in 1775. His company, known as “Morgan’s riflemen” marched from Virginia to Boston in 21 days. These Southerners and frontiersmen quickly gained a reputation for their hard fighting ways and the incredible accuracy of their rifles. They also distinguished themselves through their dress. Morgan and his men wore hunting shirts, a distinctly American garment that soon struck fear in the British Army because of the known accuracy of the American riflemen, and soon became a common uniform item in the Continental Army. Later in 1775, Morgan participated American expedition to invade Canada organized by General Benedict Arnold. During the Battle of Quebec, Arnold suffered a wound to his leg, forcing command of the American forces on Morgan. The combat, however, resulted in his capture along with 400 other Americans. His release several months later was followed by his promotion to colonel of the 11th Virginia Regiment.

One of Morgan’s most valuable qualities as a commander was his ability to think beyond the confines of the accepted standards of warfare. Not long after becoming colonel, he was placed in charge of a corps of light infantry made up of Virginians, Pennsylvanians, and Marylanders and he began to employ tactics designed to disturb the disciplined Royal troops. He and his men wore Indian disguises and used hit-and-run maneuvers against the British in New York and New Jersey throughout 1777.

Later in 1777, Morgan was assigned to General Horatio Gates' army and participated in the pivotal Battle of Saratoga. During one of the engagements near Saratoga, one of Morgan’s riflemen killed British General Simon Fraser and helped turn the tide of the battle.

Morgan was indispensable to the Continental Army during the Saratoga campaign, but he grew irritated when he repeatedly failed to receive promotions. The commander-in-chief appointed Morgan colonel of the 7th Virginia Regiment, but he was continually passed over for promotion, forcing him to resign.

By 1780, Patriot forces in the South were desperate for Morgan’s services. Morgan initially refused to rejoin the army, but after Horatio Gates’ disaster at the Battle of Camden, Morgan returned to service as a brigadier general. Once Nathanael Greene assumed command of the Southern Department, he gave Morgan command of a "flying army" and assigned him to the South Carolina backcountry.

Morgan’s main adversary was British Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. Tarleton and Morgan’s forces faced each other at Cowpens in South Carolina on January 17, 1781. Morgan emerged victorious and secured his reputation as a skilled military tactician. Utilizing knowledge of his enemy’s aggressive and impulsive behavior, Morgan lured Tarleton into a trap with a fake retreat. Tarleton charged, only to be surprised when Morgan’s infantry turned to fire and a hidden cavalry force joined the conflict. The victory was complete and was a turning point in the war in the South. .

In 1790, Congress granted Morgan a gold medal for his victory at Cowpens. Morgan continued to serve in the militia, leading a force against the Whiskey Rebellion agitators in 1794. He also went on to serve one term in the House of Representatives as a Federalist.

It is of course possible that it was Daniel's copy. He was a no-nonsense person not known for his bookishness in any way; this perhaps explains his lack of ownership mark. Or, his son could have acquired it elsewhere to aid in his military career.

Now Willoughby Morgan [1785-1832] has a fascinating and rather sad story. Immediately in the aftermath of the American Revolution, Willoughby's father, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan had an affair. Willoughby was the result of the tryst. Daniel Morgan did officially recognize Willoughby as his son but would have nothing to do with him and stayed off all attempts at relationship. The mother’s name has never be revealed and he was not mentioned in the General's letters, memoirs, or will.

Share