Specs Fine Books

1780 HOWARD SIMEON. The Divine Origin of Government by the People and Theological Rational for Revolution

1780 HOWARD SIMEON. The Divine Origin of Government by the People and Theological Rational for Revolution

Couldn't load pickup availability

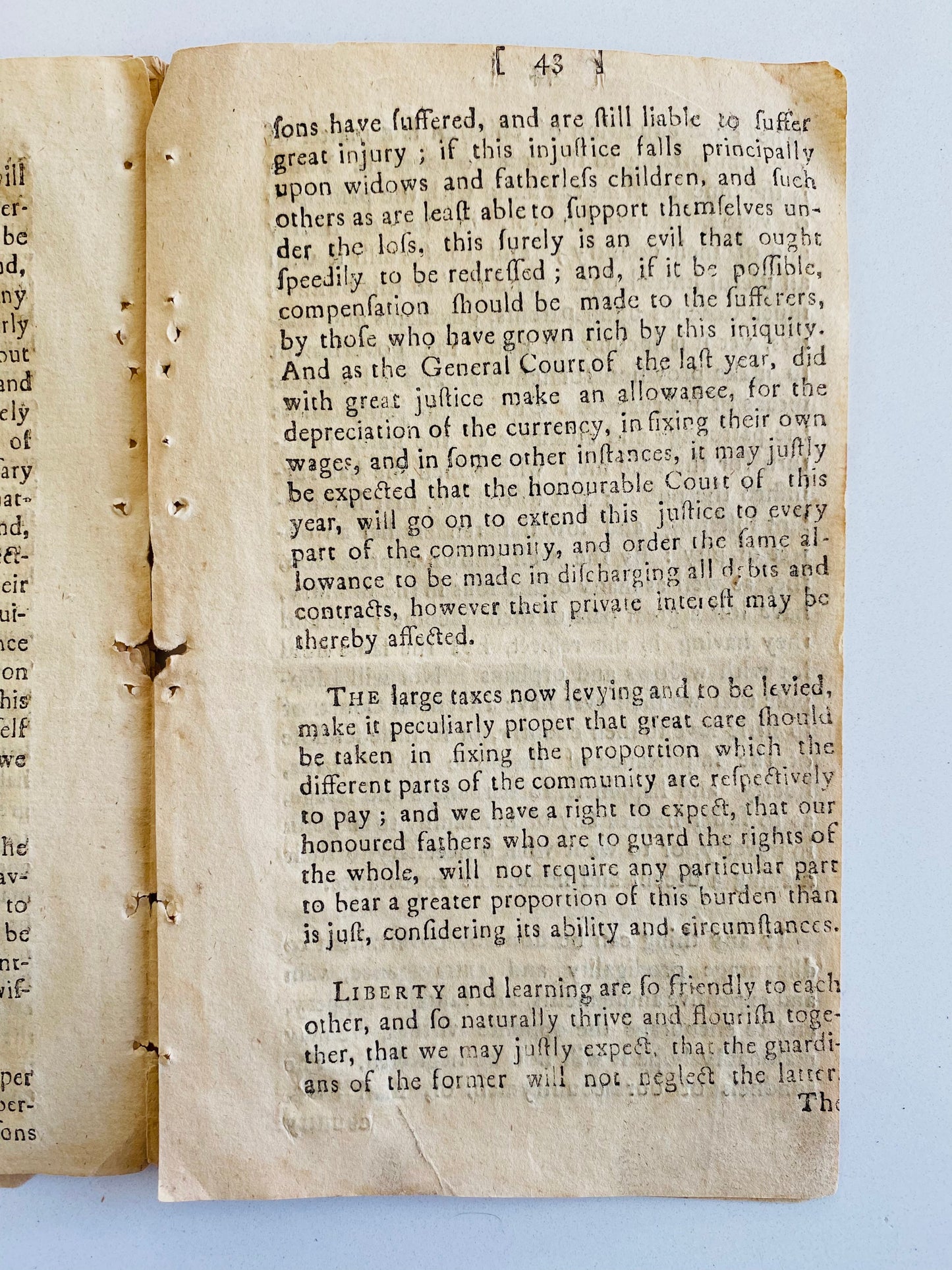

Howard, Simeon. A Sermon Preached before the Honorable Council, And the Honorable House of Representatives of the State of Massachusetts-Bay in New-England, May 31, 1780. Being the Anniversary for the Election of the Honorable Council. By Simeon Howard, A. M. Pastor of the West Church in Boston. Boston, New-England: Printed by John Gill, in Court-Street. 1780. 48pp.

Simeon Howard [1733-1804] was one of the leading pro-American Revolution agitators from the pulpit. As early as 1773, he was preaching that was the work of God in the human life and heart and that when a government ceased to participate in that work, it became the enemy of both God and man and was thus subject, by holy people, to overthrow!

The present very important sermon preached in the heat of the American Revolutionary War on Exodus 18.21, Thou shalt provide out of all the people, able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and place such over them to be rulers, communicating the virtues of a godly Government for the “new Israel” of the United States. In it he also explores the role of Government and provides a fascinating and rather innovative articulation wherein God reserves to Himself the right to make laws and institutes Governments to administrate and enforce those decrees. This is a straight lift, though freshly articulated, from the Scottish Covenanters [which influenced so much of the early American theology of “God’s Nation.”]

The sermon is divided thusly; I. The necessity of Civil Government to the Happiness of Mankind; II. The Right of the People to Choose their Own Rulers; III. The Business of Rulers in General; and IV. The Qualifications Necessary for Civil Rulers.

Extracts:

“No man is born a magistrate, or with a right to rule over his brethren. If this were the case, there must be some special mark by which it might be known to whom this right belongs. . . If a man by the improvement of his reason and moral powers becomes more wise and virtuous than his brethren, this renders him better qualified for authority than others; but still he is no magistrate or lawgiver until he is appointed such by the people.”

“Nor has one state or kingdom a right to appoint rulers for another. This would infer such a natural inequality in mankind as is inconsistent with the equal freedom of all. One state may indeed by virtue of its superior power assume this right; and the weaker state may be obliged to submit to it, for want of power to resist. But it is an unjust encroachment upon their liberty, which they ought to get rid off as soon as they can: It is a mark of tyranny on one side, and of inglorious slavery on the other.”

“The magistrate is properly the trustee of the people: He can have no just power but what he receives from them. To them he ought to be accountable for the use he makes of this power. But if a man may be invested with the power of government, which is the united power of the community, without their consent, how can they call him to account; what check can they have upon him; or what security for the enjoyment of any thing which he may see fit to deprive them of? They must in this case be slaves: But as every people have a right to be free, they must have a right of choosing their own rulers and appointing such as they think most proper; because this right is so essential to liberty, that the moment a people are deprived of it, they cease to be free.“

“The business of rulers in general is to promote and secure the happiness of the whole community. For this end only they are invested with power, and only for this end ought it to be employed. . . This is the sold end for which God has ordained, that magistrates should be appointed, that they may carry out his benevolent purposes, in promoting the good and happiness of human society; and hence their power is said to be from God; that is, it is so, while they employ it according to his will. But when they act against the good of society, they cannot be said to act by authority from God, any more than a servant can be said to act by his master’s authority while he acts directly contrary to his will. And no people, we may presume, ever elected a magistrate for any other end, than their own good; consequently when a magistrate acts against this end, he cannot act by authority from the people; so that he acts, in this case, without any authority either from God or man.”

“Rulers should be . . . able men of good understanding and knowledge; men of clear heads, who have improved their minds by exercise, acquired an habit of reasoning and furnished themselves with a good degree of knowledge: Men who have a just conception of the nature and end of government in general, of the natural rights of mankind, of the nature and importance of civil and religious liberty . . .”

“There can be no doubt but God often brings distress and ruin upon a sinful people, through the ill-management of their rulers, given up to error and blindness.”

“But let every one remember, that whatever others may do, and however it may fare with our country, it shall surely be well with the righteous; and when all the mighty states and empires of this world shall be dissolved and pass away like the baseless fabric of a vision, they shall enter into the kingdom of their father which cannot be moved, and in the enjoyment and exercise of perfect peace, liberty, and love, shine forth as the sun forever and ever.”

Half title badly chipped, no blank rfep; disbound. Textually complete and sound with some turned corners.Share