Specs Fine Books

1812 ISAAC WATTS. Psalms, Hymns, & Spiritual Songs w/ Revolutionary War Hero & George Washington Private Guard Provenance!

1812 ISAAC WATTS. Psalms, Hymns, & Spiritual Songs w/ Revolutionary War Hero & George Washington Private Guard Provenance!

Couldn't load pickup availability

Here is a nicely preserved little piece of Americana with some lovely provenance.

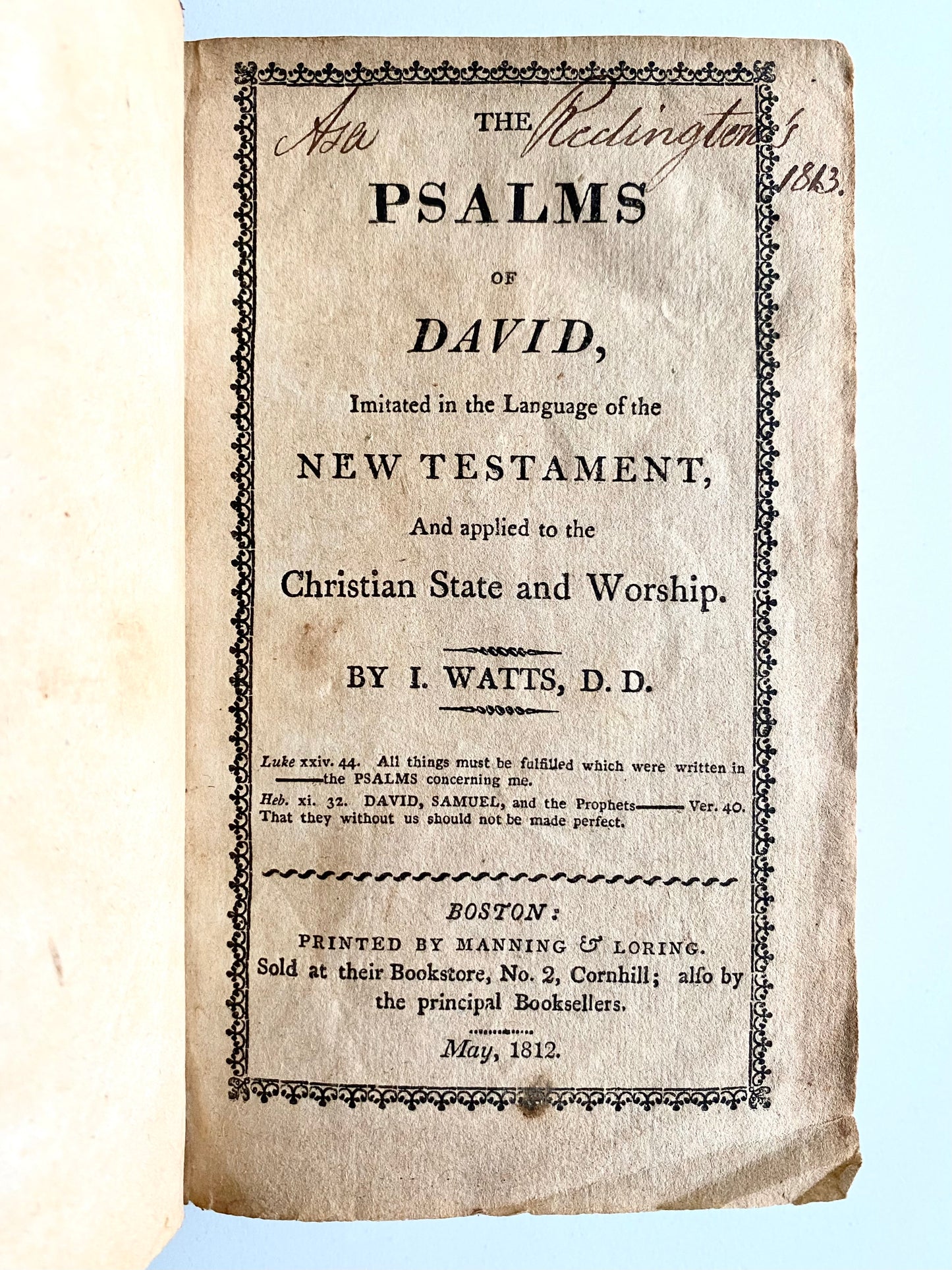

In addition to being a very nice bespoke copy of Watts' classic printed during the War of 1812, it belonged to Asa Redington. Redington was one of three men to enlist in the American Revolution from Waterville, Maine. He served through three enlistments and rose to enjoy a place in George Washington's Honor Guard, essentially what is now the Secret Service assigned to the President.

For a more detailed account of his career, see below.

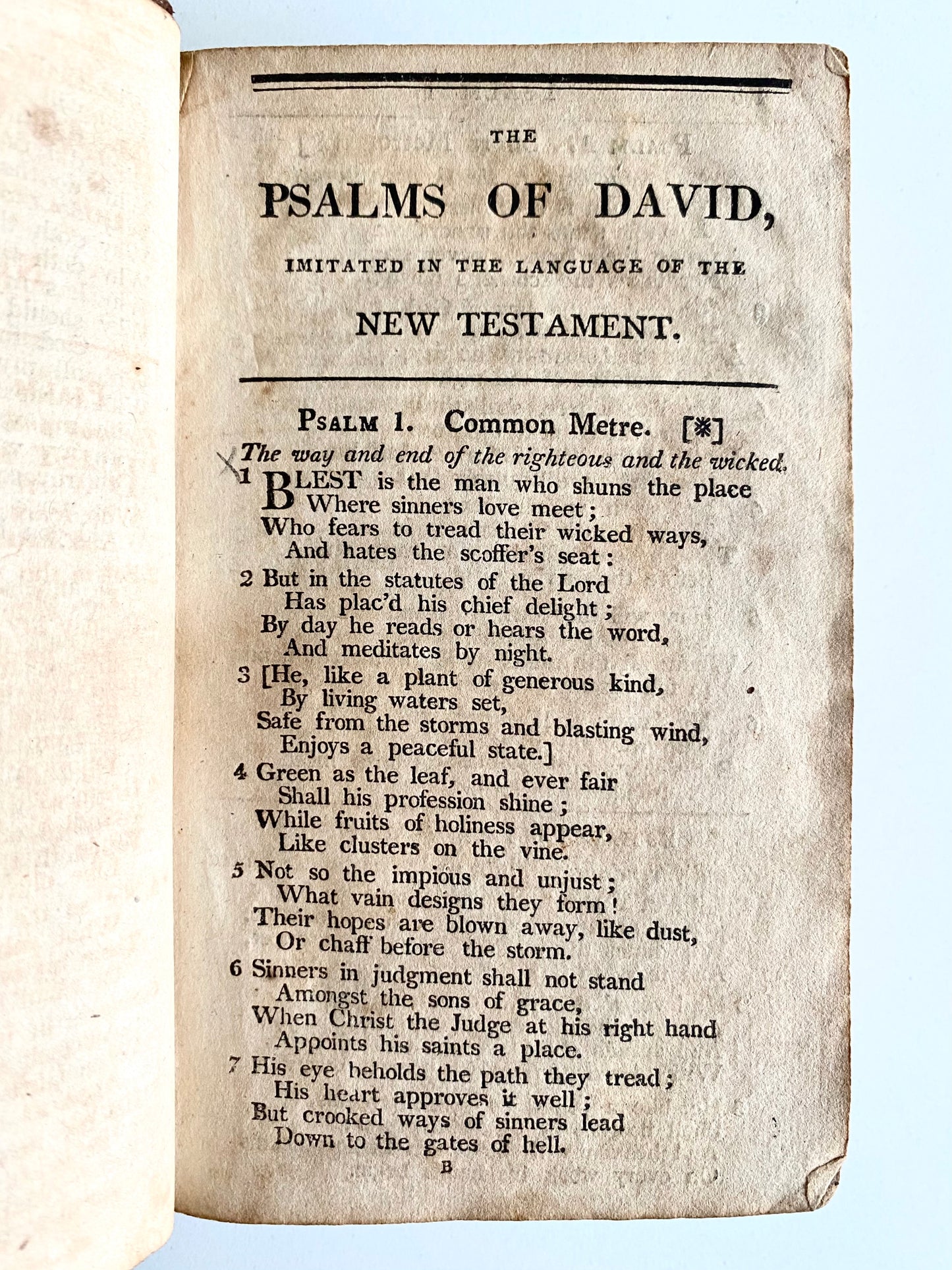

Watts, Isaac. The Psalms of David, Imitated in the Language of the New Testament; and Applied to the Christian State of Worship. Boston. Printed by Manning & Loring. May, 1812.

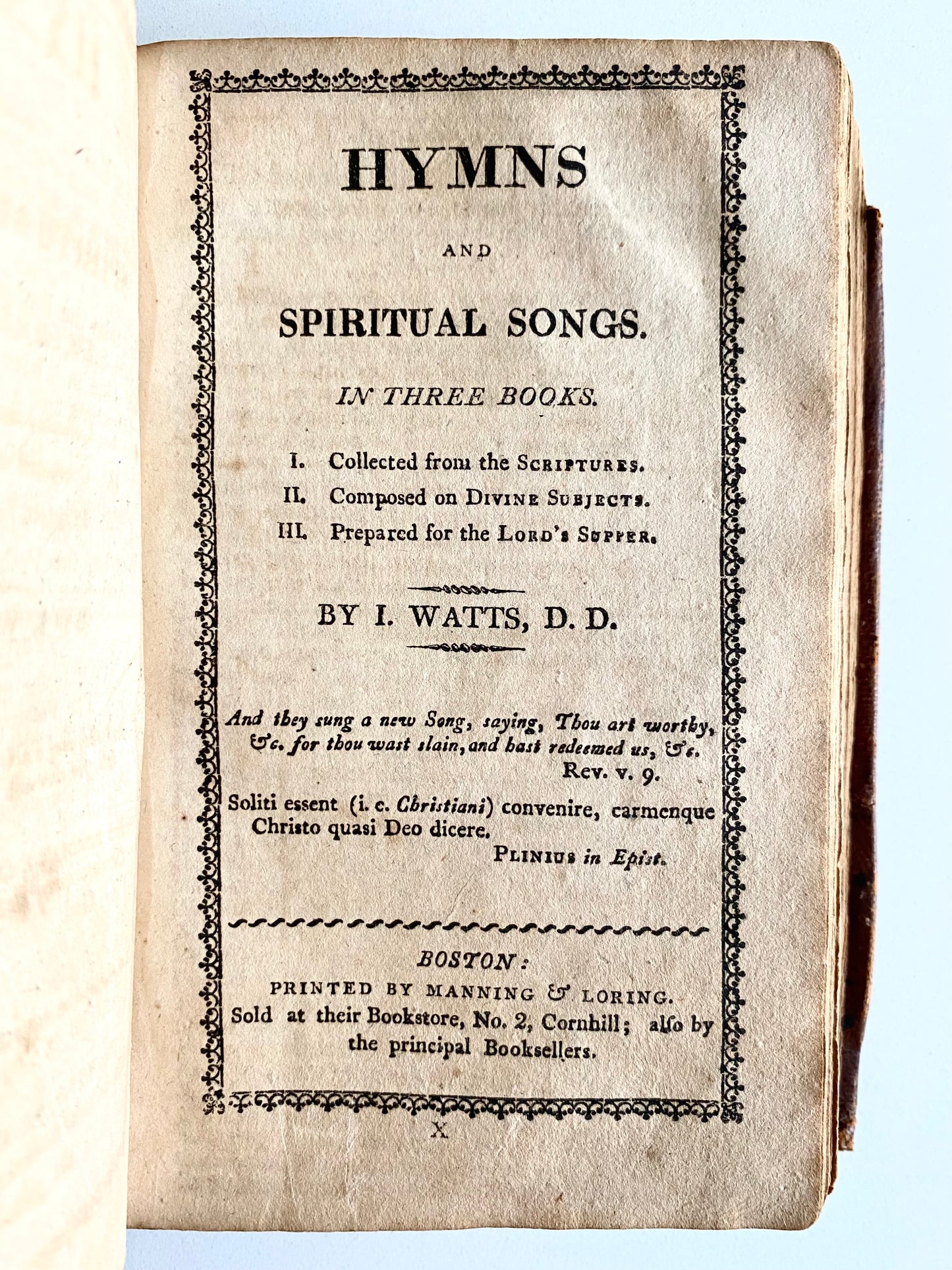

[bound with]

Hymns and Spiritual Songs. In Three Books [Complete]. Boston. Printed by Manning & Loring. 1812. 468pp [continuously paginated].

Attractive and sound full calf, some light deterioration at corners, nicely patinated, some scattered foxing and handling with a few closed tears and marginal losses, but on the whole quite a tidy, attractive, and well-provenanced piece of Americana.

Asa Redington’s first experienced the American Revolution as a soldier in the 1st New Hampshire Regiment [1778, Colonel Peabody]. There he survived battlefield experiences at the Battle of Rhode Island (1778), the Battle of King’s Bridge (1781), and the Siege of Yorktown, where he fought in Alexander Hamilton’s battalion of light infantry on the night of Hamilton’s famous attack on the British battery ‘Redoubt No. 10’.

His unpublished autobiography recounts:

“Early in the morning the British on Quaker Hill had got their Cannon to bear upon us, & opened a heavy fire, & their shot fell thickly about us & did considerable execution. Lieut. Dearborn belonging to my company had his head carried away by a cannon ball & fell down dead at my feet – and a young man a mess mate of mine by the name of Hastings had his leg carried away by one of these missiles of destruction – Orders were soon given for the Regt. to leave the ground & retire to the main body of the Army, in doing which, we had to ascend a long piece of rising ground in plain view of the enemies battery, which poured upon us a destructive fire until we passed over the high ground & descended into a valley – Small parties were then sent back to take off the dead & wounded … While marching up the ascending ground a cannon ball struck the ground a few feet behind me, & threw up a column of earth, with such force against me as to completely prostrate my face to the earth – & I hardly knew for a moment whether I was dead or alive. I heard the men sing out “that fellow is dead”. I however soon convinced them of their error …”

That night, “the Americans silently removed their artillery & stores & passed them over Howland ferry, & by day light the next morning the Army had left the Island …”

During his second and third enlistments the Regiment was deployed along the Hudson River under the command of Col. Alexander Scammell, who was later killed at Yorktown: unmourned by Redington and his fellow soldiers, who suffered under his “severe discipline”. Redington was a regular part of scouting parties that frequently involved intense military action, the passage down the Hudson River to the outskirts of British occupied “York Island” (Manhattan) and to the site of his second major military engagement at the Battle of King’s Bridge in July, 1781. This action, which involved Washington’s main army, also resulted in an American retreat at which Redington again nearly lost his life:

Again, from his unpublished autobiography:

“We moved down the [Hudson] River to near Dobbs Ferry when we landed under the side of a mountain on the Jersey side of the River … About 9 o’clock in the evening we again embarked … and landed about 2 o’clock in the morning of 3 July … about 2 ½ miles above Kings bridge and apparently undiscovered … We then took up the line of march … and proceeded toward K. bridge where the enemy had a strong post … it was about half way between day [break] and sun rising. In a few minutes after we were thus posted, a body of the B. Cavalry came dashing along the road, and were immediately fired upon, some of whom were shot down and left dead in the road …

“The enemy soon began to muster on York Island, both infantry & Cavalry. I could see their arms glistening in the sun in many places on the high lands … By this time we were joined by Col. Sprout’s Regt. of about 400 men, making on the whole 900 men … At about 8 o’clock in the morning the enemy let down their Bridge and a large body of Infantry and Cavalry advanced upon us and a severe action ensued. The Americans were commanded by Gen. Lincoln – we were overpowered by numbers and retreated … getting however, behind double walls, & keeping up a fire upon them, retarding their advance – We were kept in close order to prevent the Cavalry from charging upon us, whom we most dreaded.

“The dead & wounded were mostly left on the ground, to the mercy of the enemy … I expected to have been killed, wounded, or made prisoner on that fearful day … After retreating about a mile hard driven by the enemy, to our great joy a large body of French Cavalry hove in sight, and immediately after the front of the main army under Washington appeared. On the discovery of this large force, the enemy gave up the pursuit …”

“About the 4th I was one of the intrenching party that marched onto the ground about 9 o’clock in the evening … we … began digging where we found a line of split white pine strips stretching along the ground, marking out the line to intrench. Our men formed in line … and began ‘to break ground’. Not a single word was spoken … The soil was light & sandy and we worked like heroes till morning light – Had by this time thrown up a mound of earth towards the enemy perhaps a ½ mile in length – digging a trench perhaps 4 feet deep & 8 feet wide … During the night they [the British] threw up many sky rockets, which burst high up in the air … to see if they could discover any intruders … About sun rising a fresh party came to relieve us, & we were permitted to take some sleep in the rear of our works. I went back a few rods, laid down on the grass, and spread my blanket over me – In a few minutes, a cannon ball passed directly over me, & like a gust of wind threw the blanket off me, the ball being itself in the ground some few rods beyond me …”

Redington also gives a detailed account of the death of Scammell, and Hamilton’s attack on Redoubt no. 10:

“The enemy had 2 redoubts some distance in advance of the main batteries & with their cannon & shells considerably annoyed the Allies, & orders were given to storm them in the night. The one nearest the French line was assigned to them, and the other to the Americans, under the command of [Lt.] Col. Hamilton … I was with Hamilton’s party & entered the works with them. The enemy had only time to make one fire which did but little execution (only 8 men I think were killed) before the works were carried … We were not permitted to load a musket, but depended wholly on the bayonet …”

After the climatic British surrender at Yorktown, Redington marched north, and became ill with smallpox. When he was recovering at an infirmary in Princeton, New Jersey, he was put under the care of General Washington’s personal physician. After his recovery, Redington continued his service in the Continental Army throughout New Jersey and New York, including Saratoga, Lake George, and between West Point and Washington’s Headquarters at Princeton, where he served the remainder of his time in Washington’s Honor Guard. These men guarded Washington personally and were precursor to the modern Secret Service appointed the President.

See here for more details: www.allthingsliberty.com/2014/08/his-excellencys-guards

Share