Specs Fine Books

1826 ALEXANDER CAMPBELL. First Edition Christian Baptist Translation of the New Testament. Scarce.

1826 ALEXANDER CAMPBELL. First Edition Christian Baptist Translation of the New Testament. Scarce.

Couldn't load pickup availability

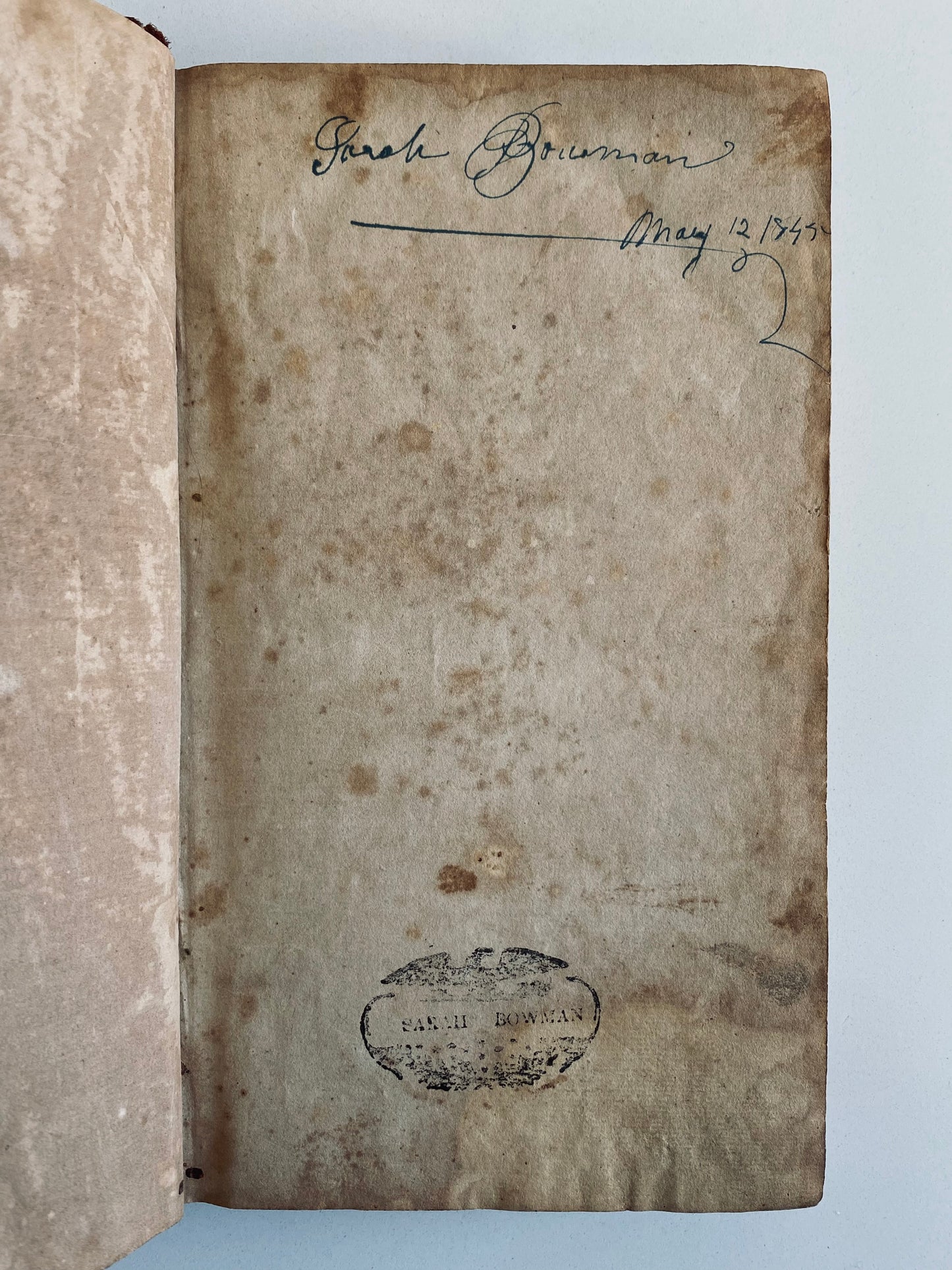

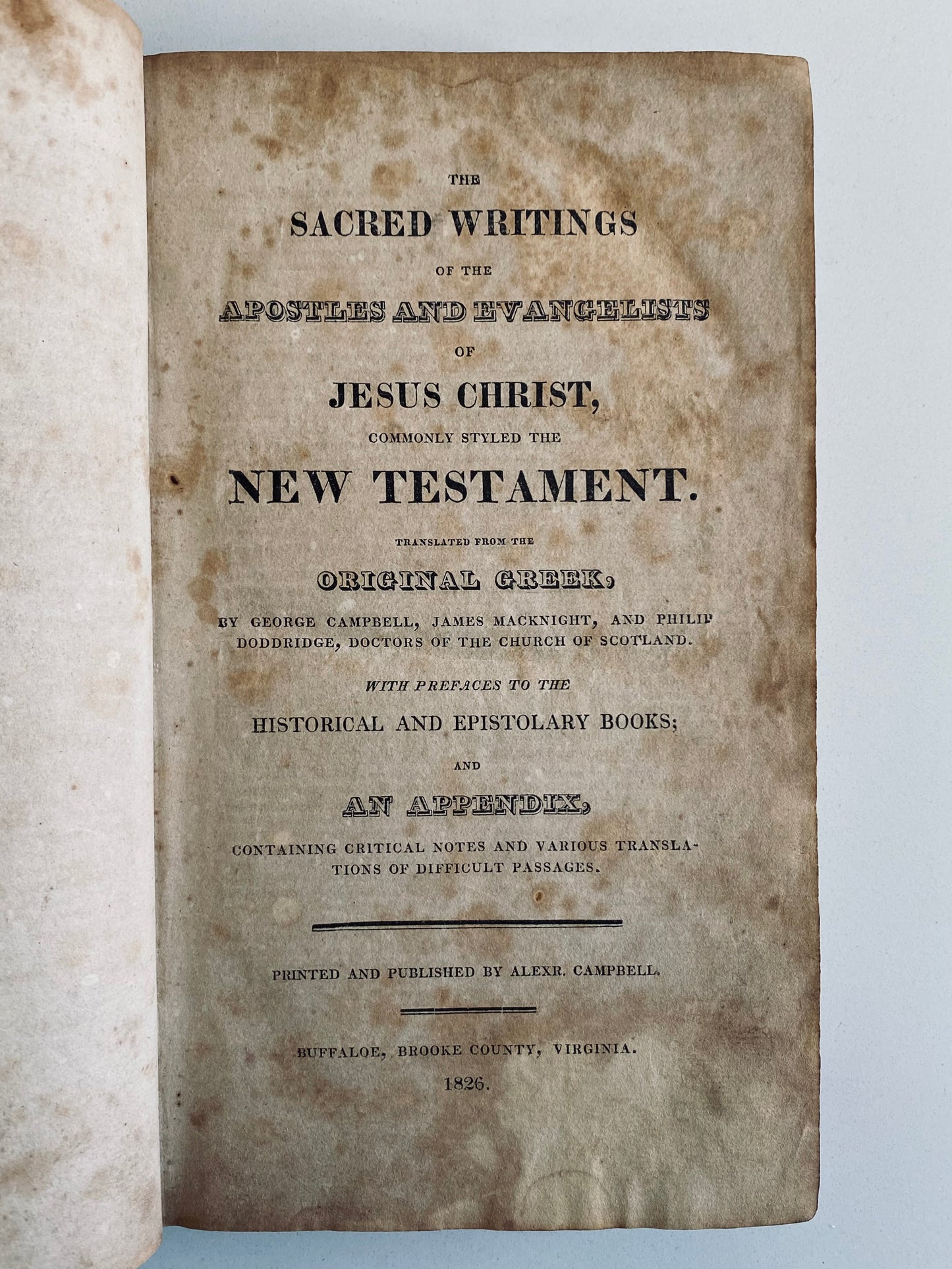

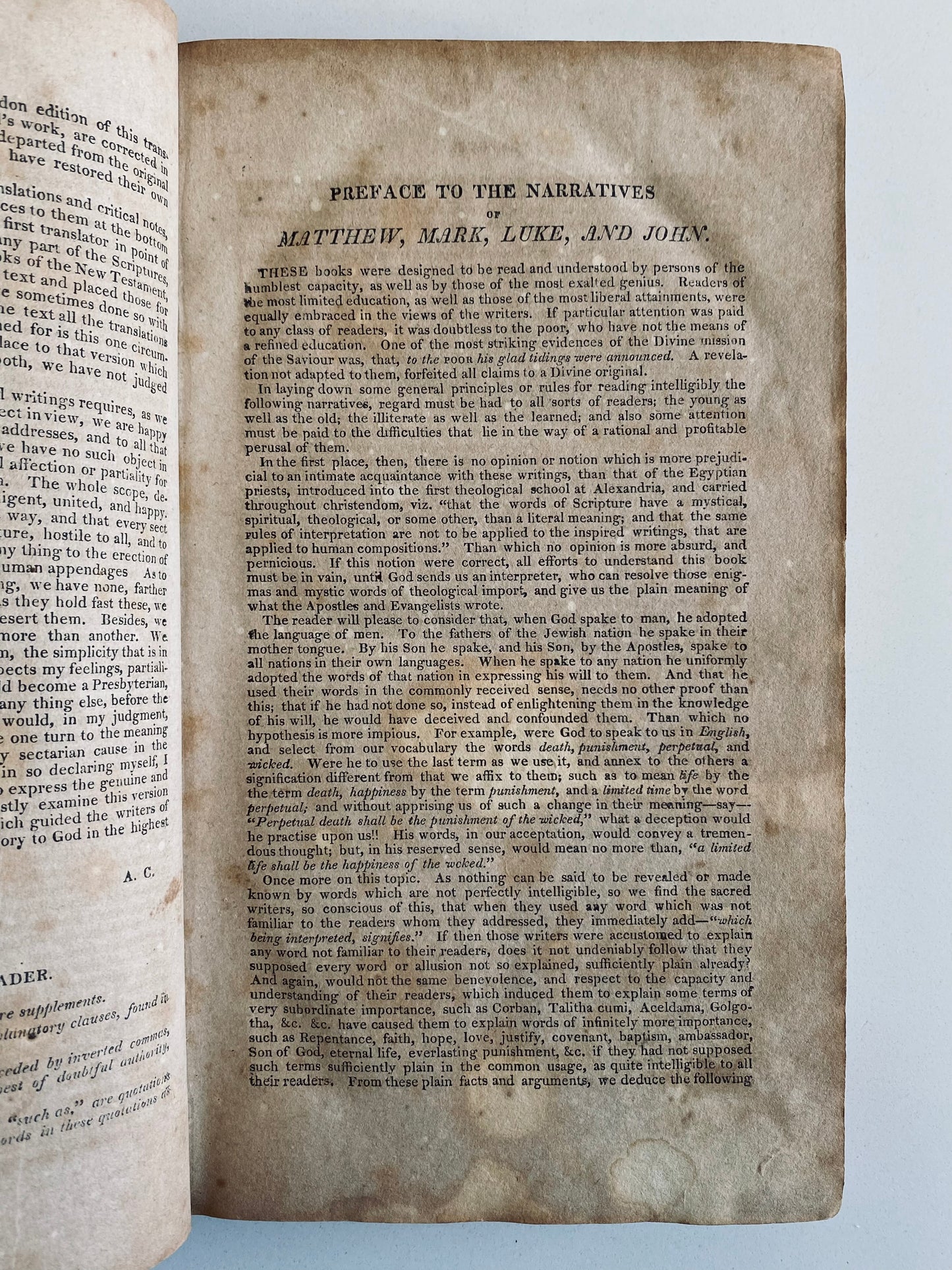

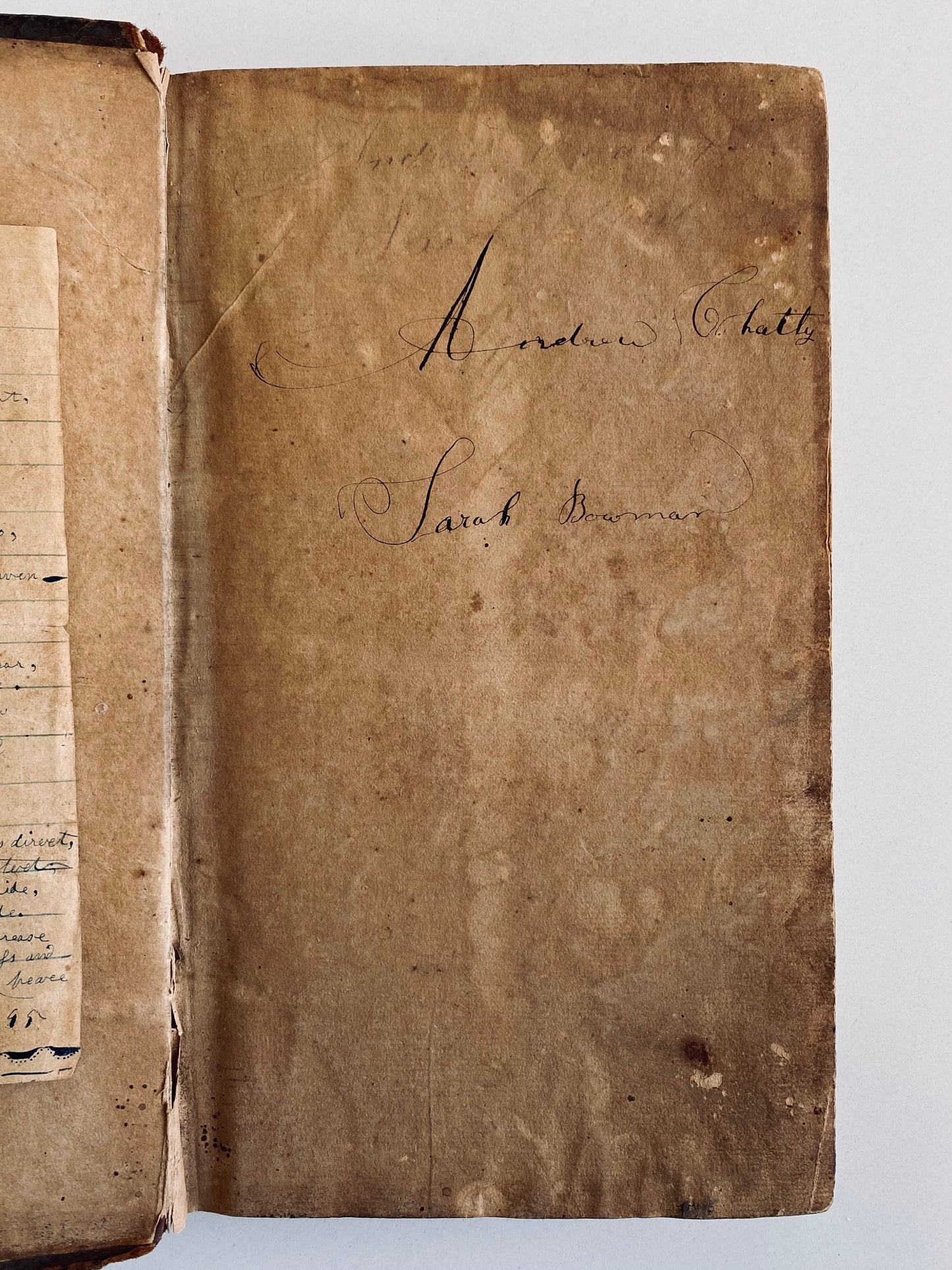

Campbell, Alexander. The Sacred Writings of the Apostles and Evangelists of Jesus Christ, Commonly Styled the New Testament. Translated from the Original Greek, by George Campbell, James MacKnight, and Philip Doddridge, Doctors of the Church of Scotland; With Prefaces to the Historical and Epistolary Books; and an Appendix, Containing Critical Notes and Various Translations of Difficult Passages. Published by Printed and Published by Alexr. Campbell. Buffaloe, Brooke Co., VA, 1826. First Edition. 478pp.

An excellent historical piece on Campbell's work is available here. It should also be noted that Campbell understates his work on the present texts. There are many readings which do not belong to MacKnight, Campbell, or Doddridge. The translation is Campbell's, though very much informed by the translators he mentions.

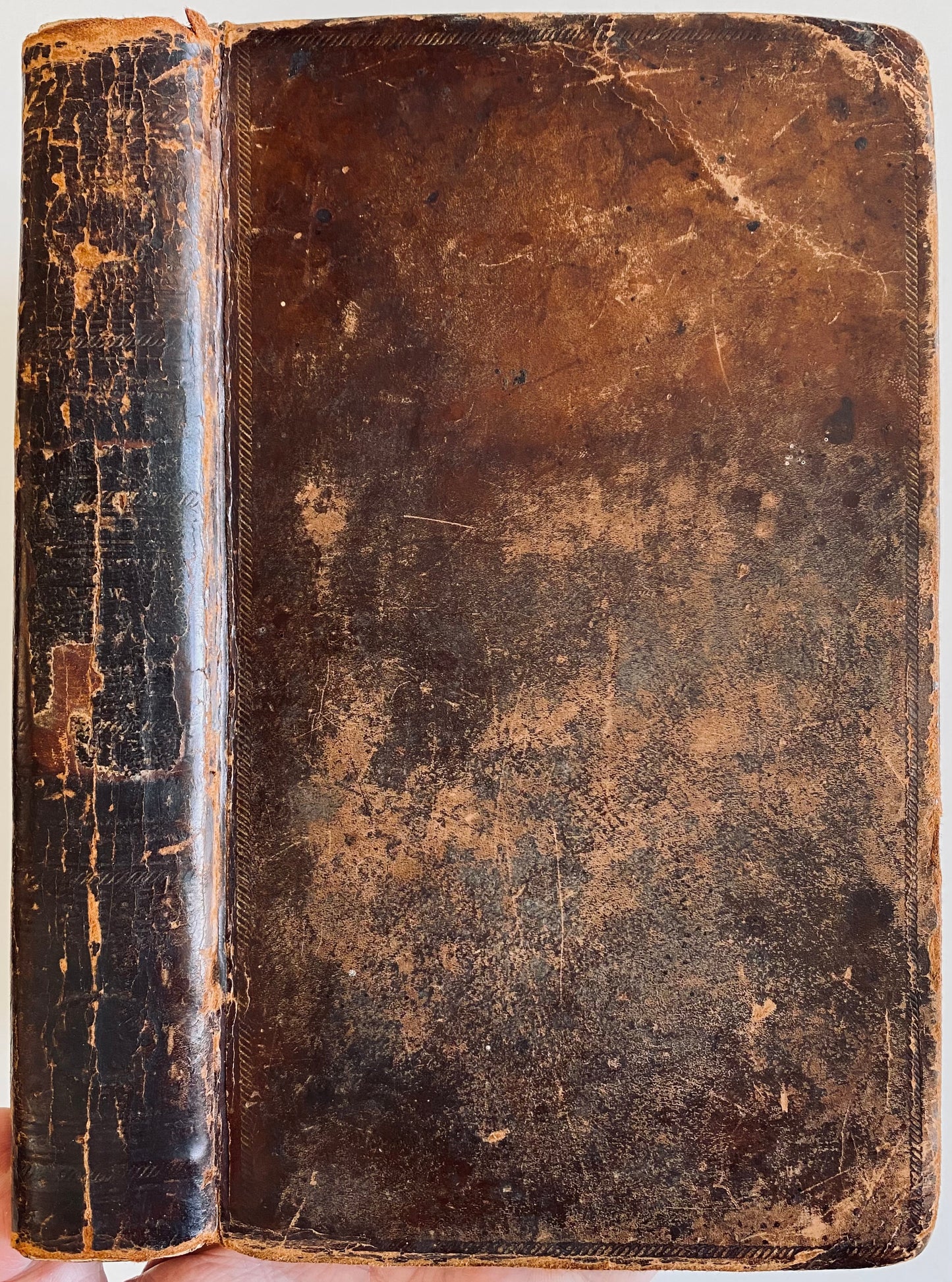

Full calf, rubbed, some minor losses. Handled. Scarce on the market.

Excerpt from Valentine's contextualization of Campbell's translation.

Alexander Campbell and the Search for Clear English

By the time Alexander Campbell immigrated to America, European civilization had occupied the land for over 200 years. In that time a plethora of translations had been made available to the reader. French Bibles and Luther’s German Bible were available and read in North America [6]. In the British colonial period the first English Bible in America was the Geneva Bible[7]. Yet by Campbell’s arrival the common version of the people was the King James Version.

The young Campbell was, however, quite dissatisfied with the “Authorized Version”[8]. Early in his reforming and publishing career, Campbell began calling for a revision, or the outright replacement, of the common version. For Campbell, reforming the church was historically linked to God’s word being put afresh in the vernacular of the common people. He wrote in his journal, the Christian Baptist, “it is a remarkable coincidence in history of all the reformers from Popery, that they all gave of the scriptures in the vernacular tongue of the people whom they labored to reform”[9]. In four brief articles Campbell sketched out the history of the English Bible from “Wickliffe” through Tyndale, the Geneva Bible, the Bishop’s Bible and finally the King James Version[10].

Reformation, according to Campbell, simply could not take place because the KJV was no longer in the clear language of the people and it contained many translation errors. Citing James MacKnight as his authority, Campbell argued the KJV frequently departed from the Hebrew to follow the Septuagint or the Latin Vulgate in the “Old Testament. The Common Version had too many “Latinisms” to be intelligible to the ordinary reader and, interestingly enough, it was too “literal” in translating Hebrew and Greek idioms. He declared that the translators allowed the King’s notions of “predestination, election, witchcraft, familiar spirits” to influence their work of translating.

Further many passages, Campbell said, were simply mistranslated and finally the division of verses into individual paragraphs severely hampered following the flow of thought for the ordinary reader [11]. The only way to remedy “those evils” in the KJV “so long and so justly complained of,” was to issue a new translation of the New Testament[12]. This is exactly what Alexander Campbell proposed to do using the works of “Doctors Campbell, MacKnight and Doddridge” as a base and revised in the light of Johann Jakob Griesbach’s critical Greek New Testament.

The New Version: Living Oracles

On April 19, 1826, Campbell announced to his readers that the new version, that is The Sacred Writings of the Apostles and Evangelists of Jesus Christ, Commonly Styled the New Testament, translated from the original Greek by George Campbell, James MacKnight, and Philip Doddridge, Doctors of the Church of Scotland, with prefaces to the historical and epistolary books with an appendix, Buffaloe, Brooke, Co., Virginia, Printed and Published by Alexander Campbell, 1826 was now available[13]. This version became known simply as “The Living Oracles” though to my knowledge this title never actually appeared on the title page until the Fourth Edition in 1835[14].

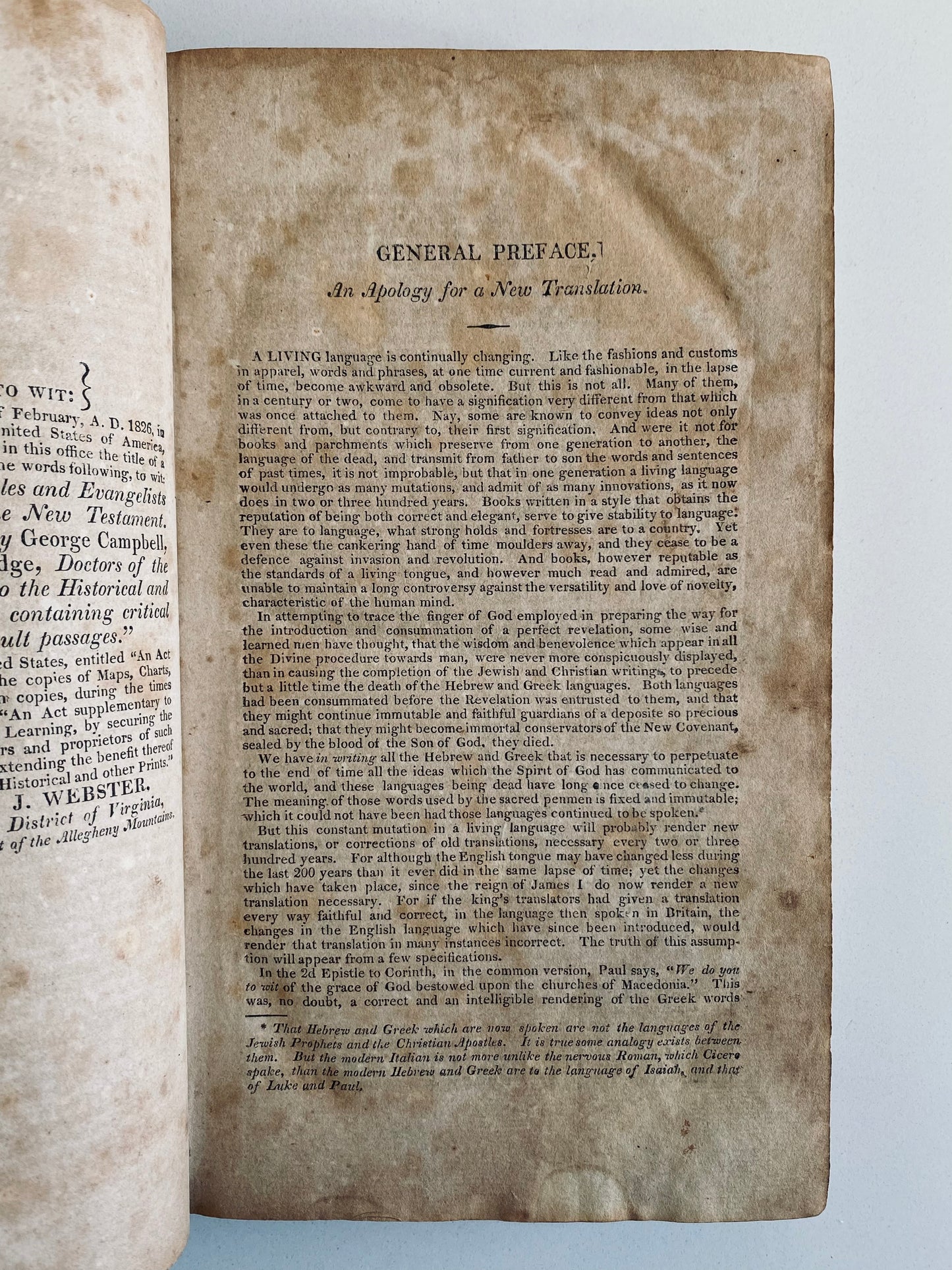

In his General Preface to the Sacred Writings, Campbell gave an apology for this new translation. His argument consists of two parts: English has changed since 1611 and the KJV is not only hard to understand in places but simply wrong in many. Campbell’s language argument is that living language is like clothing fashions “at one time current and fashionable” and then “awkward and obsolete”[15]. The first example he gives drives home the point with clarity. Referring to 2 Corinthians 8.3 “we do you to wit,” Campbell says “this was, no doubt, a correct and intelligible rendering … to the people of that day; but to us it is as unintelligible as the Greek original”[16]. Then he lists more examples such as “conversation,” “double-minded,” “prevent,” among many more and more that could be listed but he refrains.

In his second argument, Campbell addressed the long noted reality that the KJV was anything but a perfect translation. He cites the special influence of Theodore Beza [17] upon the 1611 translators giving the version a clear “sectarian” character [18]. His final argument is from the advance in biblical studies, especially the knowledge of Greek and Hebrew. He notes that special character of NT Greek, with the LXX influence, has the “body of Greek but the soul of Hebrew” as he correctly put it. The translators of 1611 did not recognize this aspect of New Testament Greek and approached the subject as a classical scholar might. Some may say the translations are literally correct but, according to Campbell, “the King’s translators have frequently erred in attempting to be, what some would call literally correct. They have not given the meaning in some passages, where they have given a literal translation”[19]. Campbell ended by arguing that Christians now have a more accurate Greek text from which to translate than was available in 1611.

The version by Campbell was a daring enterprise for the day. The Sacred Writings has been called the “first modern translation” [20] because of its dependence on the critical Greek text and its move toward current modern English. Because Campbell intended to maximize readability and comprehension the text of the new version was divided into paragraphs which omitted verse numbers except at the beginning of the paragraph [21].

The shift to current English in the Living Oracles can readily be seen in passages like Philippians 3.20 where the KJV reads “our conversation is in heaven” but Campbell rendered it “but we are citizens of heaven.” Romans 14.1 in the KJV reads “but not to doubtful disputations” and Campbell translates “without regard to differences of opinions.” Campbell avoided special ecclesiastical words in his version. One looks in vain for “church” or “baptize” instead we read “congregation” and “immerse.” “Repent” becomes “reform” and “hell” becomes “hades.” In the first edition Campbell rendered parakletos as “Monitor” but rejects this in the second edition using the term Advocate departing from the KJV’s Comforter. Campbell thus anticipated twentieth century versions in his translation: the RSV reads “Counselor,” NEB reads “Advocate,” the Jerusalem Bible reads “Advocate,” the NIV reads “Counselor,” and the NRSV reads “Advocate.”

Just as with many twentieth century translations that depend upon the critical Greek text, it was Campbell’s commitment to textual criticism that embroiled him in bitter controversy. He rejected the “Received Text” as inferior asserting that “Griesbach’s Greek Testament is the most correct in christendom”[22]. This commitment to presenting the authentic wording of the text in translation led Campbell to print many passages in italics that Griesbach regarded as doubtful. These doubtful texts range from a single word to entire passages, including John 7.53-8.11[23]. Passages omitted from the Living Oracles were the Doxology at the end of the Lord’s Prayer (Mt 6.13, KJV); the Ethiopian’s confession (Acts 8.37, KJV); the phrase “through his blood” in Colossians 1.14 and the Three Heavenly Witnesses in 1 John 5.7[24]. Ultimately three hundred and fifty seven readings were placed in the table of “Spurious Readings” by Campbell.

Campbell’s rejection of the reading theos in favor of Lord in Acts 20.28 brought charges of denying the deity of Christ, Unitarianism and Socianism. An anonymous “Friend of Truth” wrote to Campbell that “this has long been viewed as a powerful text in opposition to those who deny the proper divinity of Christ … I am sorry that Mr. Campbell makes the change.” The Friend of Truth insinuates that Campbell may be guilty of Unitarianism himself![25] Campbell defends the the reading of Lord on the basis of Griesbach, and an appeal to Irenaeus. For Campbell, the Friend of Truth, did not want to deal with the textual evidence for the reading so he had to resort to casting aspirations upon Campbell’s orthodoxy. Our pioneer Bible reviser writes pointedly,

“For although I am as firmly convinced of the proper divinity of the Saviour of the world, that he is literally and as truly the Son of God as the Son of Man, as ever John Calvin was, I would not do as this ‘Friend of Truth’ insinuates I ought have done, made the text bend to suit my views” [26]

Campbell argued there was nothing to fear from new translations. “The weak minded only are afraid of new translations” he wrote. New versions do not add to or take away any cardinal truth of Christianity nor threaten Christians by producing heterodoxy. Rather he told the readers of the Christian Baptist that “the illiterate have stronger faith who read many translations, than the same class who have read but one”[27]. One “weak minded” person actually acquired a copy of the Living Oracles and then proceeded to literally burn it after he compared it to the “common version” or the King James Version [28]. Another congregation had teachers who refused to read the new version because it was not “the word of God”[29]. Campbell responded with tongue firmly planted in his cheek to these misguided disciples:

“Your teacher was certainly right, and you should all passively submit to his determination. For the common version is the word of God, but the new one is not. The reason I will tell you. The common version was made by forty-nine persons authorized by the king, and paid for their trouble by the king, and when their work was published the king ordered it to be read as the word of God in the public assemblies and in families, to the exclusion of every other version … You see there are two things necessary to constitute any translation the word of God; first that it be authorized by a king and his court; and again, that it be finished by forty-nine persons … by such arguments as these my dear sir, we prove the common version to be the word of God and the new to be the word of man. If any man has any better arguments than these to offer, we shall cordially thank him for them” [30]

Alexander Campbell believed these disciples to be badly mistaken to think that only the King James Version was the word of God. Surely such people, Campbell argued, just had not thought through their argument. He asked them, if the KJV is truly the only word of God then “have the French, the Spanish, the Germans, and all the nations of Europe, save the English, no Word of God?” Then the Translator states “I would thank some of those ignorant declaimers to tell us where the Word of God was before the reign of king [sic] James!” [31] He goes on in bold language “taken as a whole, it [KJV] has outlived its day at least one century, and like a superannuated man, has failed to be as lucid and communicative as in its prime” [32].

C. K. Thomas in his extensive study of Campbell’s Living Oracles prepared a chart comparing it with the RSV showing its decided tendency towards current English [33]. I have edited the chart to include the NIV for contemporary comparison. (I am trying to figure out how to insert this table …)

(Chart to be here later)

The chart clearly demonstrates movement to modern and intelligible speech.

Reception of the Living Oracles Among Disciples

The Living Oracles clearly reveal Alexander Campbell’s fundamental attitude toward the King James Version. His work was welcomed among those in the Restoration Movement going through six editions from Campbell’s press and reprinted numerous times after that. Two episodes may be noted to show how popular this translation was among the Disciples of Christ. The famous preacher “Raccoon” John Smith was called to give an account of his preaching before the Baptists Association Meeting at Cane Spring in 1827. Smith was charged with breaking three tenants of the Baptist tradition. I will list only one pertinent to our point here. The charge reads,

1. That, while it is the custom of Baptists to use the the Word of God King James translation, he [Smith] had, on two or three occasions in public, and often privately in his family, read from Alexander Campbell’s translation. [34]

John Smith’s response to the charges was “I plead guilty.” When Smith was allowed to defend himself he addressed a certain elder who had declared the King’s version to be the only word of God and asked him if he really meant it. Williams narrates the story,

“Yes,’ said the elder bravely, ‘I said so, and I still say it.’ ‘How long, my brother,’ said Smith, ‘has it been since the king made his translation?’

‘I don’t know,’ said the elder, defiantly ignorant. ‘Was it not about two hundred and twenty years ago?’ Smith asked of the clerk, who, perhaps had read more than his brethren.

‘I believe it has been about that time,’ he replied.

‘Then is it not a pity,’ continued Smith, that the apostles left the world and the Church without any Word of God for fifteen hundred years? For, as these intelligent citizens around me know, they wrote Greek, without the least knowledge of the language into which King James, fifteen hundred years afterward, had their writings translated! But if nothing is the Word of God but the King’s version, do you not brethren pity the Dutch, who have not that version, and who could not read one word of it, if they had it‘”[35]

The incident involving ‘Raccoon’ John Smith provides some insight into how widespread the use of Campbell’s new version was. It also helps us understand the official censure of the Baptists in the Appomattox Decrees. The Decrees were aimed at stifling the influence of Campbell’s reforming ideas among them. So prevalent was Campbell’s version among disciples and apparently some non-reforming churches that it is singled out for mention in the Decrees. It reads, “Resolved, That it be recommended to all churches in this Association, not to countenance the new translation of the New Testament“[36]. The string of evidence we have examined so far shows that DeHoff’s and Wallace’s conclusion is nothing but rhetoric. The King James Version was not the Bible of the early Stone-Campbell Movement rather it was what became known as the Living Oracles [37]. This was recognized by David Lipscomb who wrote in 1890 these words,

“it is a mistake that the reformation was based upon it [KJV]. Alexander Campbell rejected it, adopted MacKnight and Doddridge’s and did more to bring about the late revision [the RV of 1881] than any other man on earth” [38].

Share