Specs Fine Books

1829 JOHN McLEOD CAMPBELL. Important Autograph Letter on Atonement by Influential Scottish Theologian.

1829 JOHN McLEOD CAMPBELL. Important Autograph Letter on Atonement by Influential Scottish Theologian.

Couldn't load pickup availability

A significant and expansive letter by one of Scotland's most significant 19th century theologians.

John McLeod Campbell [1800 –1872] was an influential Scottish minister and Reformed theologian. James B. Torrance considers his work on atonement as important as those of Athanasius of Alexandria and Anselm of Canterbury.

As with most Scottish theologians, Campbell’s starting place was the early Church Fathers, the historic Reformed confessions and catechisms, John Calvin, Martin Luther's commentary on Galatians, and Jonathan Edwards' works. He built from there in ways many today consider important. Others, of course, would see his construction as deviant.

Licensed as a preacher by the presbytery of Lorne, Scotland in 1821, he took his first pastorate in the parish of Row, Scotland [not Rhu]. According to his telling, the town was full of crime and violence and the only preaching was that of an angry God, damnation, and eternal damnation. What on earth Christianity did, meant literally, was not clear.

Campbell took on the structure of the Fathers, Creeds, Calvin, Luther, and Edwards, but then deviated in important ways; again, variously received. He began preaching a universal atonement. In the year 1829, the year of our lengthy letter on the subject, the presbytery called him in to review the orthodoxy of his preaching and teaching.

At issue was the theology of Campbell and his conformity to the Westminster Standards, which all Scottish ministers agreed to preach and teach at their ordination. A first petition was withdrawn; but a subsequent appeal in March 1830 led to a presbyterial visitation, and an accusation of heresy. Campbell clearly disagreed with the Westminster Confession of Faith's view of a limited atonement, and he was removed from the ministry. The General Assembly, by which the charge was ultimately considered, found Campbell guilty of teaching heretical doctrines and deprived him of his living. He was given invitation to join Edward Irving in the Catholic Apostolic Church, but declined, instead beginning work as an evangelist in the Scottish Highlands.

Returning to Glasgow in 1833, Campbell was minister for sixteen years in a large chapel specially built for him by close friends. In 1859 his health gave way, and he advised his congregation to join the Barony church, where Norman Macleod was pastor.

In 1856 Campbell published his most significant work, The Nature of the Atonement, which profoundly influenced Scottish theology. Campbell's theological aim was to view the Atonement in the light of the Incarnation. In the Atonement, one may not separate the birth, person, work, and death of Jesus Christ. As one looks more closely at Christ, one may discover that the divine mind in Christ is the mind of perfect obedient sonship towards God and perfect brotherhood towards men. Jesus Christ in his person fulfills the law to love God wholeheartedly and to love neighbor selflessly. By the light of this divine fact of the Incarnation, Christ's life as atonement, vicariously lived in humanity's place, is seen to develop itself naturally and necessarily as a perfect and complete reconciliation; the penal element in the sufferings of Christ is reflected then as but one aspect or facet of the atonement.

In 1868 he received the degree of D.D. from Glasgow University for his theological work and writing. He and his friends took it to be a reaching out on the part of the Scottish church towards him so long after his deposition from the ministry. It was clear that his book on the atonement was significant and required some response. In 1870 he moved to Rosneath, and there began his Reminiscences and Reflections, an unfinished work published after his death by his son.

Today, Campbell's influence may be seen particularly in the work of Hugh Ross Mackintosh, Donald Baillie, and most notably in Thomas F. Torrance and James B. Torrance. Later Scottish theology affirmed Campbell's influence in its departure from the strict reading of Westminster's Standards. Campbell, through the influence of the Torrance brothers, has begun to be appreciated as a significant pastoral theologian.

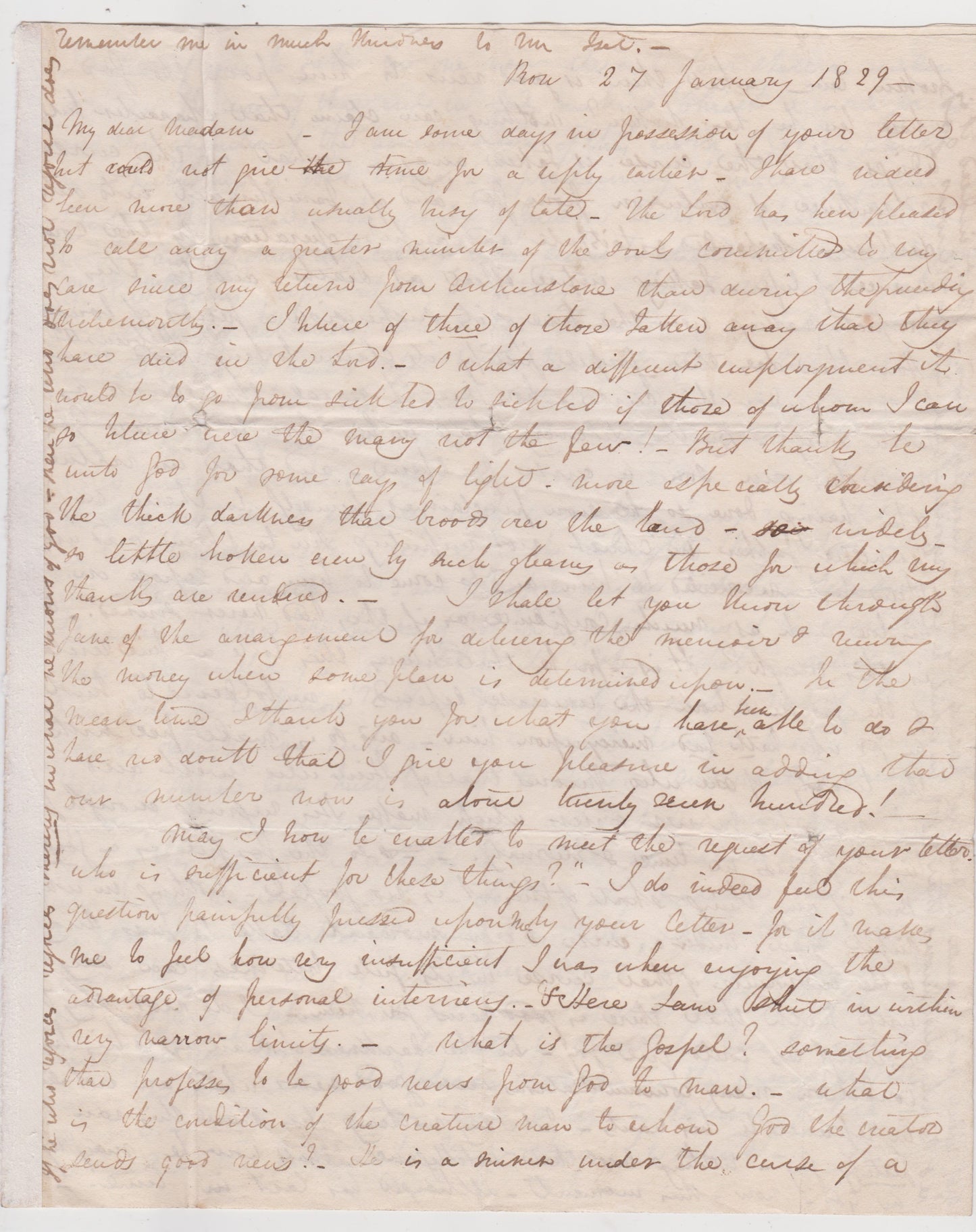

"Row 27 January, 1829

My dear Madam - I am some days in possession of your letter, but could not give the time for a reply earlier. I have indeed been more than wholly busy of late. The Lord has been pleased to call away a greater number of the souls committed to my care since my return from ****** than in the preceding twelve months. I believe of three of those ***** away that they have died in the Lord. O what a different employment it would be to go from sickbed to sickbed if those of whom I can state were the many not the few! But thanks be unto God for some rays of light. More especially considering the thick darkness that broods over the land. . . .

. . . I shall let you know through Jane of the arrangement for altering the ***** and having the money when some place is determined upon. In the mean time I thank you for what you have been able to do & have no doubt that I give you pleasure in adding that our number now is above twenty-seven hundred!

May I now be enable to meet the request of your letter. Who is sufficient for these things? I do indeed feel this question painfully pressed upon me by your letter - for it makes me to feel how very insufficient I was when enjoying the advantage of personal interviews. And here I am now shut in within such very narrow limits. What is the Gospel? Somethat that professes to be good news from God to man. What is the condition of the creature man to whom God the Creator sends good news? He is a sinner under the curse of a broken law. What then is good news to him from the God whose law he has broken? Nothing can claim that character but tidings that the curse has been taken away. What is the curse? A sentence of exclusion from God and banishment into outer darkness - suspended as to its full and awful operation by the continuance of life - taking entire effect at death - and by this prospect making even the time of its suspension a period of bondage.

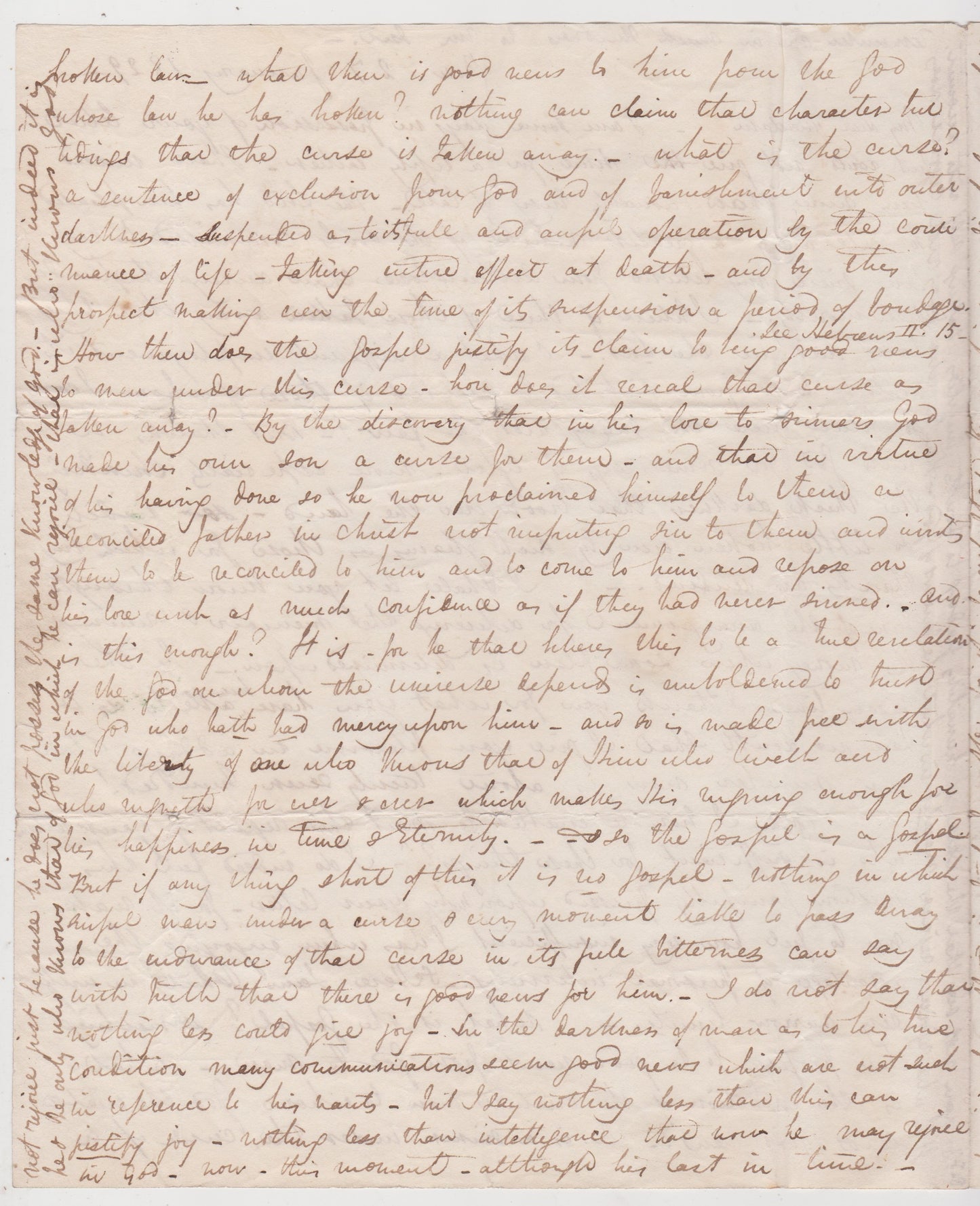

How then does the Gospel justify its claim to being good news so ever under this curse - how does it reveal that curse as taken away? By the discovery that in His love to sinners, God made His own Son a curse for them - and that in virtue of His having done so he now proclaimed Himself to them a reconciled Father in Christ, not imputing sin to them and inviting them to be reconciled to him and to come to him and repose on His love with as much confidence as if they had never sinned. And is this enough? It is. For he that believes this to be a true revelation of the God on whom the universe depends is emboldened to trust in God who hath had mercy upon him - and so is made free with the liberty of one who knows that of Him who liveth and who reigneth for ever and ever which makes his ****** enough for his happiness in time and eternity. And so the Gospel is a Gospel. But if anything short of this, it is no gospel. Nothing in which sinful men remain under a curse and every moment liable to pass away to the endurance of that curse in its full bitterness can say with truth that there is good news for him. I do not say that nothing less could give joy. In the darkness of man as to his true condition many communications seem good news which are not such in reference to his wants. But I say nothing less than this can justify joy. Nothing less than intelligence that now he may rejoice in God - now - this moment - although his last in time . . .

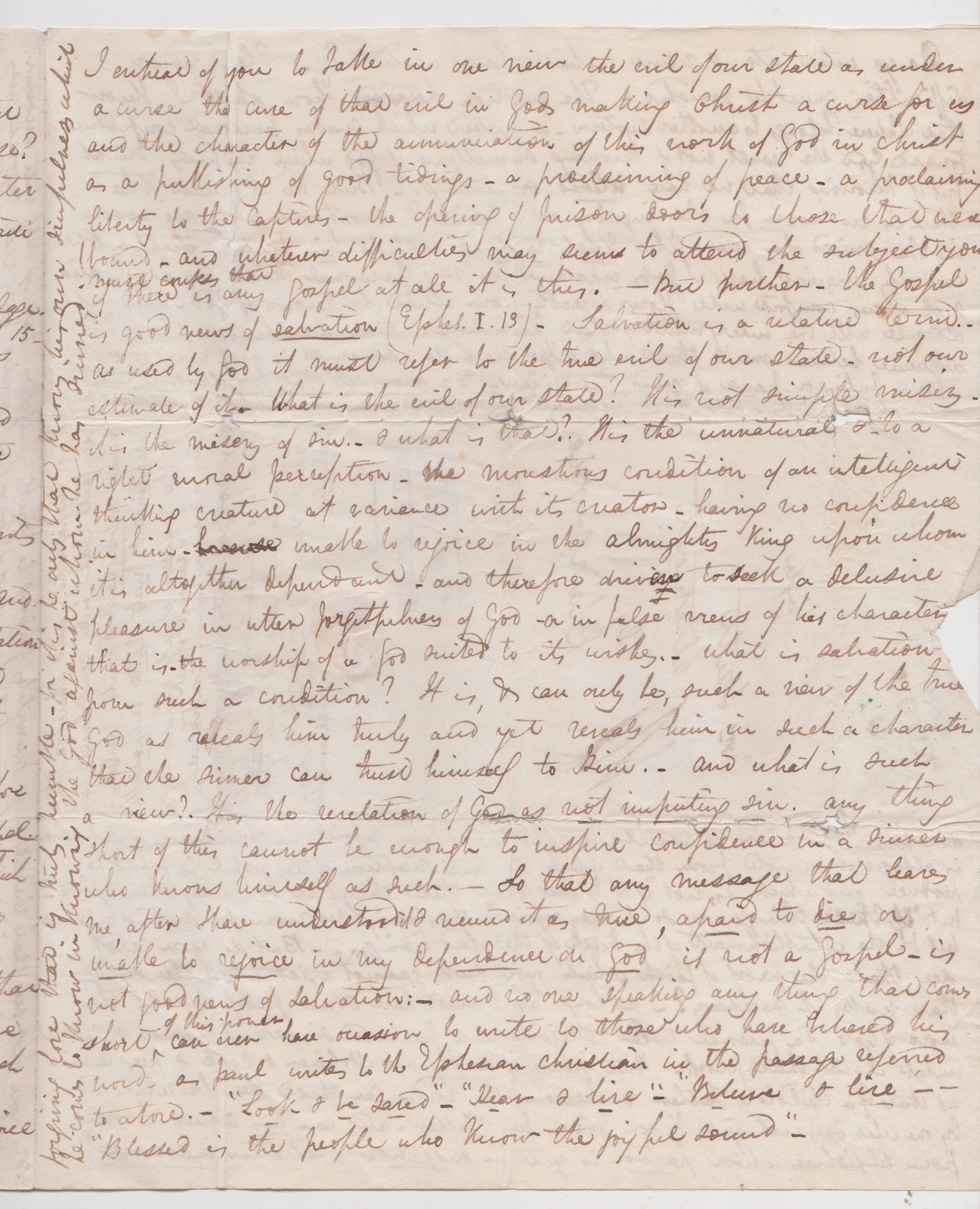

. . . I intreat you to take in one view the evil of our state as under a curse, the cure of that evil in God's making Christ a curse for us, and the character of the annunciation of this work of God in Christ as a publishing of Good Tidings - a proclaiming of peace - a proclaiming liberty to the captives - the opening of prison doors to those that were bound - and whatever difficulties may seem to attend the subject, you must confess that if there is any Gospel at all, it is this. But further, the Gospel is good news of Salvation. Salvation is a relative term . . . as used by God it must refer to the true evil of our state - not our estimate. What is the true evil of our state? It is not simple misery. It is the misery of sin. And what is that? It is the unnatural ***** to a right moral perception - the monstrous condition of an intelligent thinking creature at variance with its creator - having no confidence in him - unable to rejoice in the almighty King upon whom it is altogether dependent, and therefore driven to seek a delusive pleasure in utter forgetfulness of God - or in false views of his character - that is, the worship of a God suited to his wishes. What is salvation from such a condition? It is, and can only be, such a view of the true God as reveals him truly and yet reveals him in such a character that the sinner can trust himself to Him. And what is such a view? It is the revelation of God as not imputing sin - anything short of this cannot be enough to inspire confidence in a sinner who knows himself as such. So that any message that leaves me, after I have understood it and received it as true, afraid to die or unable to rejoice in my dependence on God, is not a Gospel - is not good news of salvation. And no one speaking any thing that comes short of this power can ever have occasion to write to those who have believed His word. As Paul writes to the Ephesian Christian in the passage referred to above, "Look & be saved" - "Hear & live" - "Believe & live" - - "Blessed is the people who know the joyful sound" -

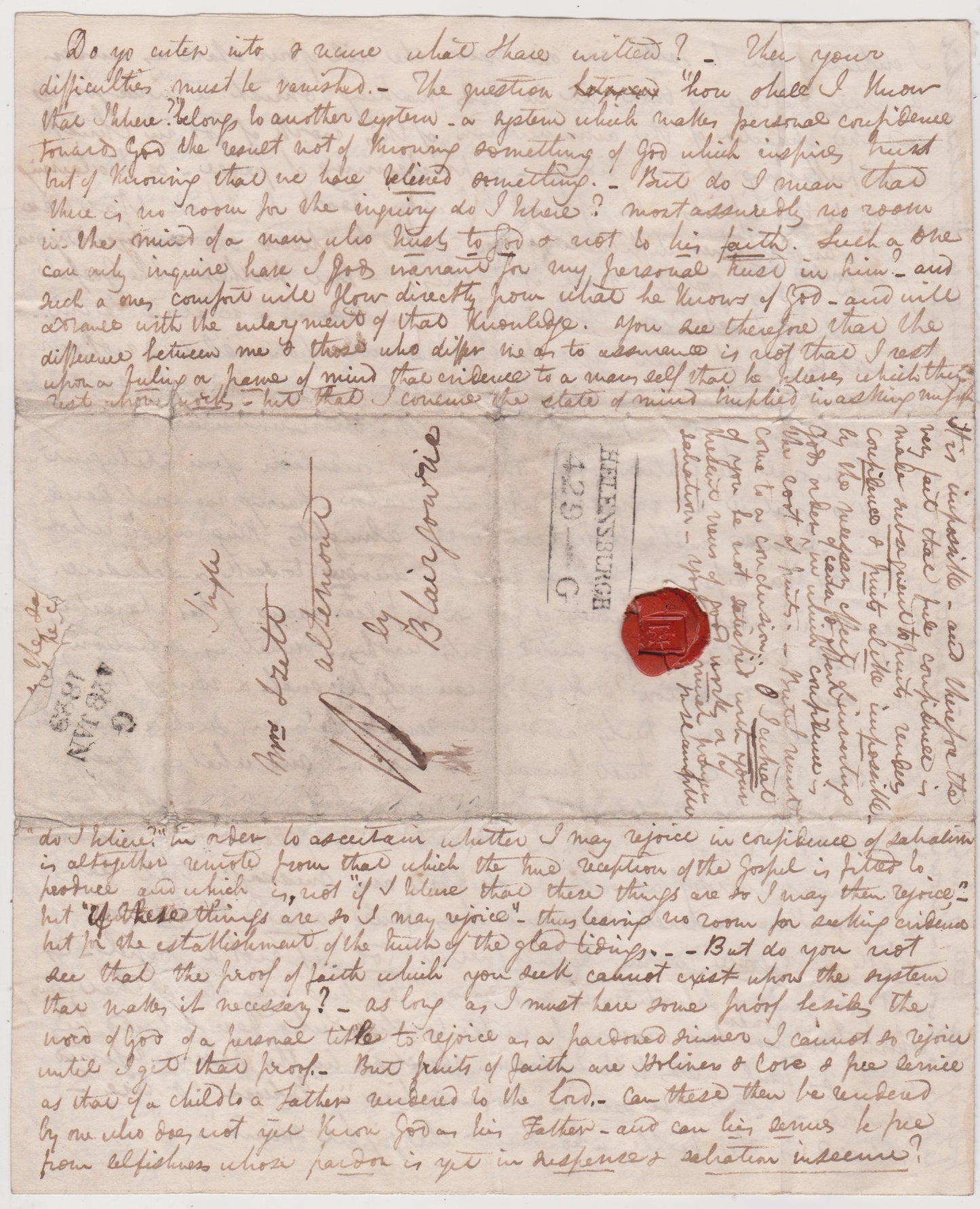

Do you enter into and receive what I have written? Then your difficulties must be vanished. The question, "How shall I know that I believe?" belongs to another system - a system which makes personal confidence towards God the result not of knowing something of God which inspires trust, but of knowing that we have believed something. But do I mean there is no room for the inquiry do I believe? Most assuredly, no room in the mind of a man who trusts God and not to his faith. Such a one can only inquire have I God's warrant for my personal trust in him? - and such a one's comfort will flow directly from what he knows of God, and will ***** with the enlargement of that knowledge. You see therefore between me and those who differ with me as to assurance is not that I rest upon a feeling or a frame of mind . . . but that I conceive the state of mine implied in asking do I believe in order to ascertain whether I may rejoice in confidence of salvation is altogether remote from that which the true reception of the Gospel is fitted to produce and which is not, "if I believe that these things are so, so I may rejoice," but "if these things are so, I may rejoice," thus leaving no room for seeking evidence, but for the establishment of the truth of the glad tidings. But do you not see that the proof of faith which you seek cannot exist upon the system that makes it necessary? As long as I must have some proof besides the word of God of a personal title to rejoice as a pardoned sinner, I cannot so rejoice until I get that proof. But fruits of faith are Holiness & Love and free service as that of a child to a father rendered to the Lord. Can these then be rendered by one who does not yet know God as his Father . . . " Etc.

An incredibly important pastoral application of Campbell's early thoughts on atonement and faith. Worthy of inclusion in scholarly work regarding an important Scottish theologian.

Share