Specs Fine Books

1849 ASTOR PLACE RIOT. Rare Illustrated Pamphlet. Police & Military Shot 50 Civilians!

1849 ASTOR PLACE RIOT. Rare Illustrated Pamphlet. Police & Military Shot 50 Civilians!

Couldn't load pickup availability

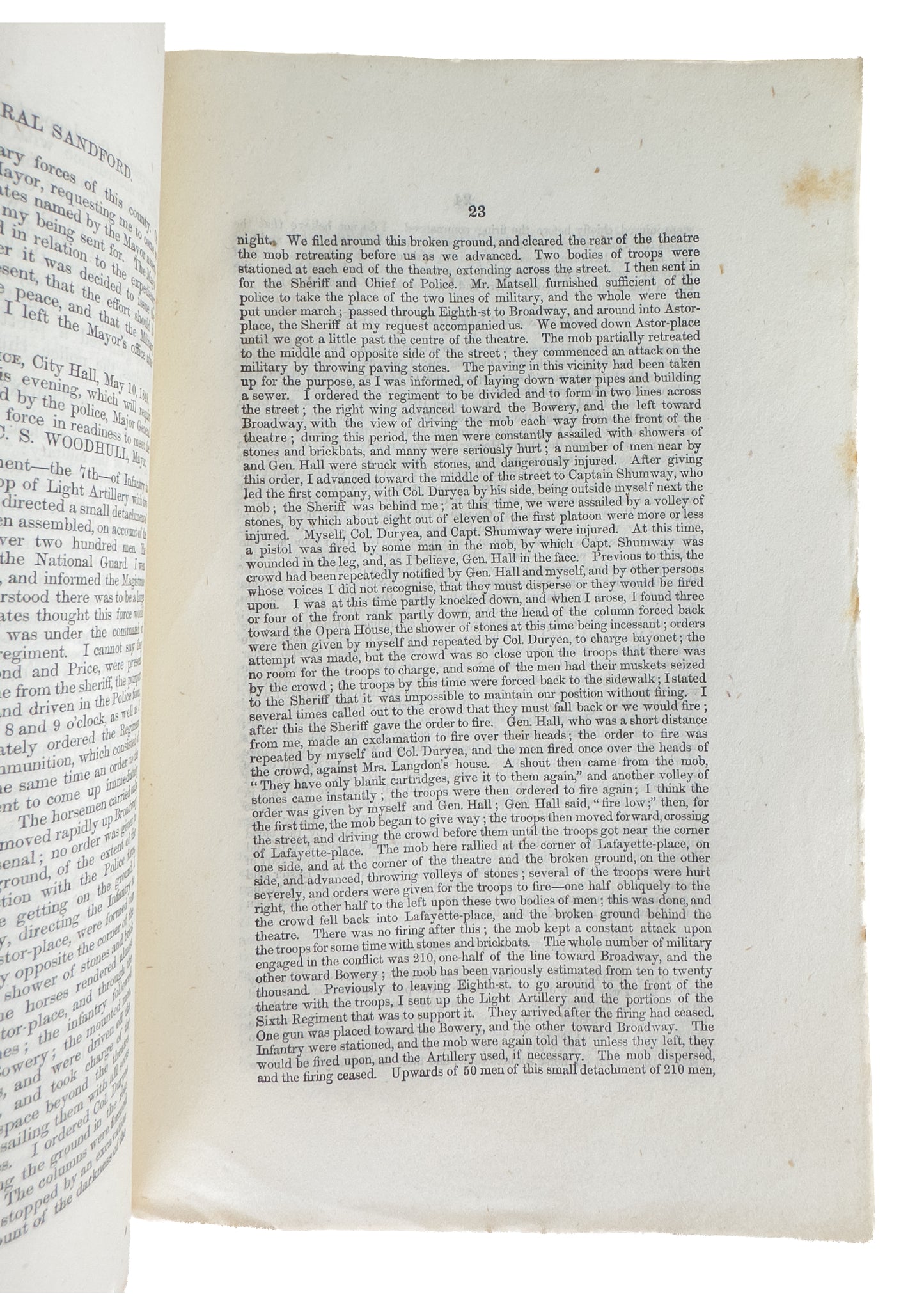

A very nicely preserved and rare original illustrated account of the Astor Place Opera House Riot of 1849. Fascinating item.

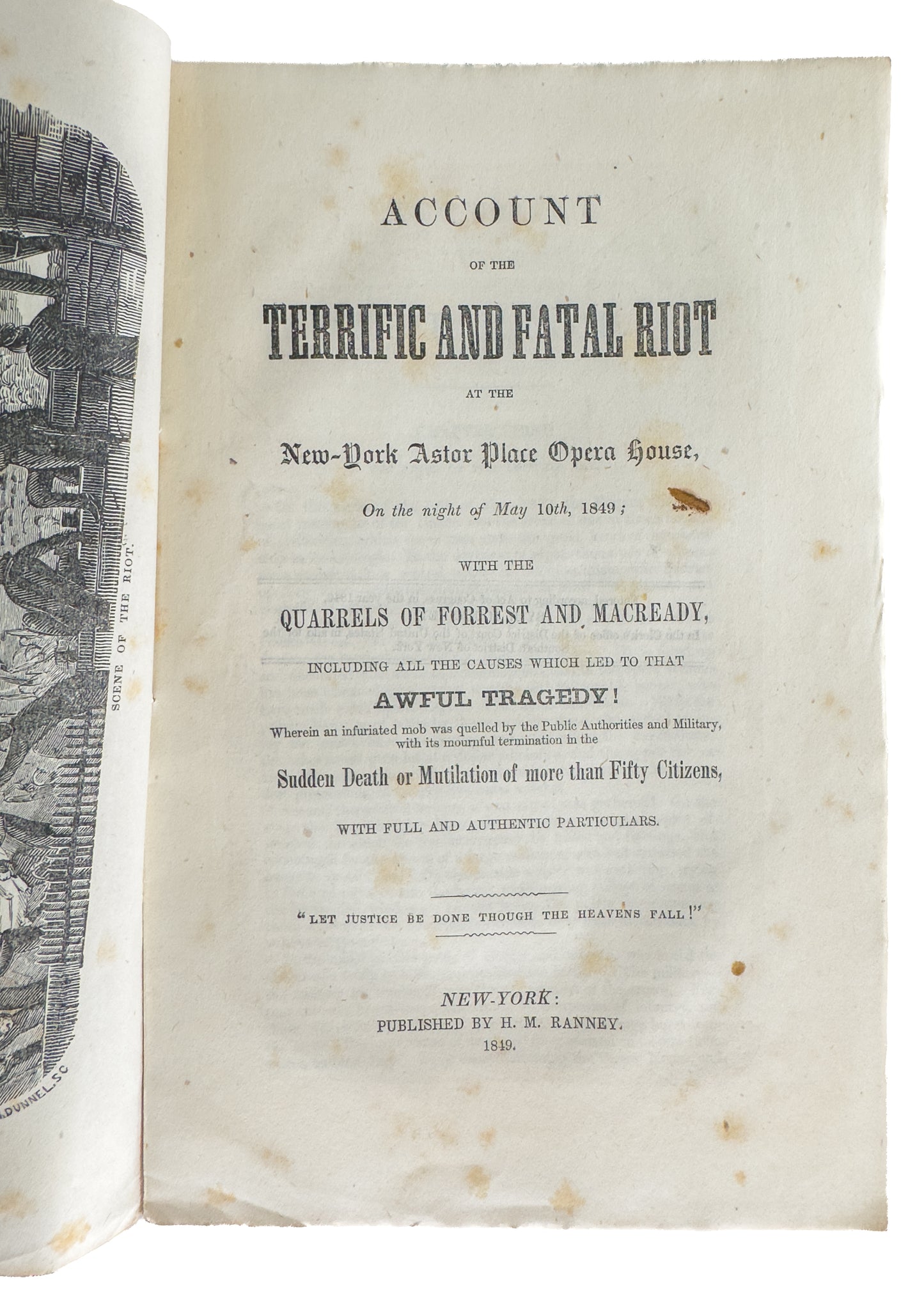

[Anonymous]. Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot at the New-York Astor Place Opera House, on the Night of May 10th, 1849; with the Quarrels of Forrest and Macready, Including all the Causes which Led to that Awful Tragedy! Wherein an Infuriated Mob was Quelled by the Public Authorities and Military, with its Mournful Termination in the Sudden Death or Mutilation of more than Fifty Citizens, with Full and Authentic Particulars. New York. H. M. Ranney. 1849. 32p.

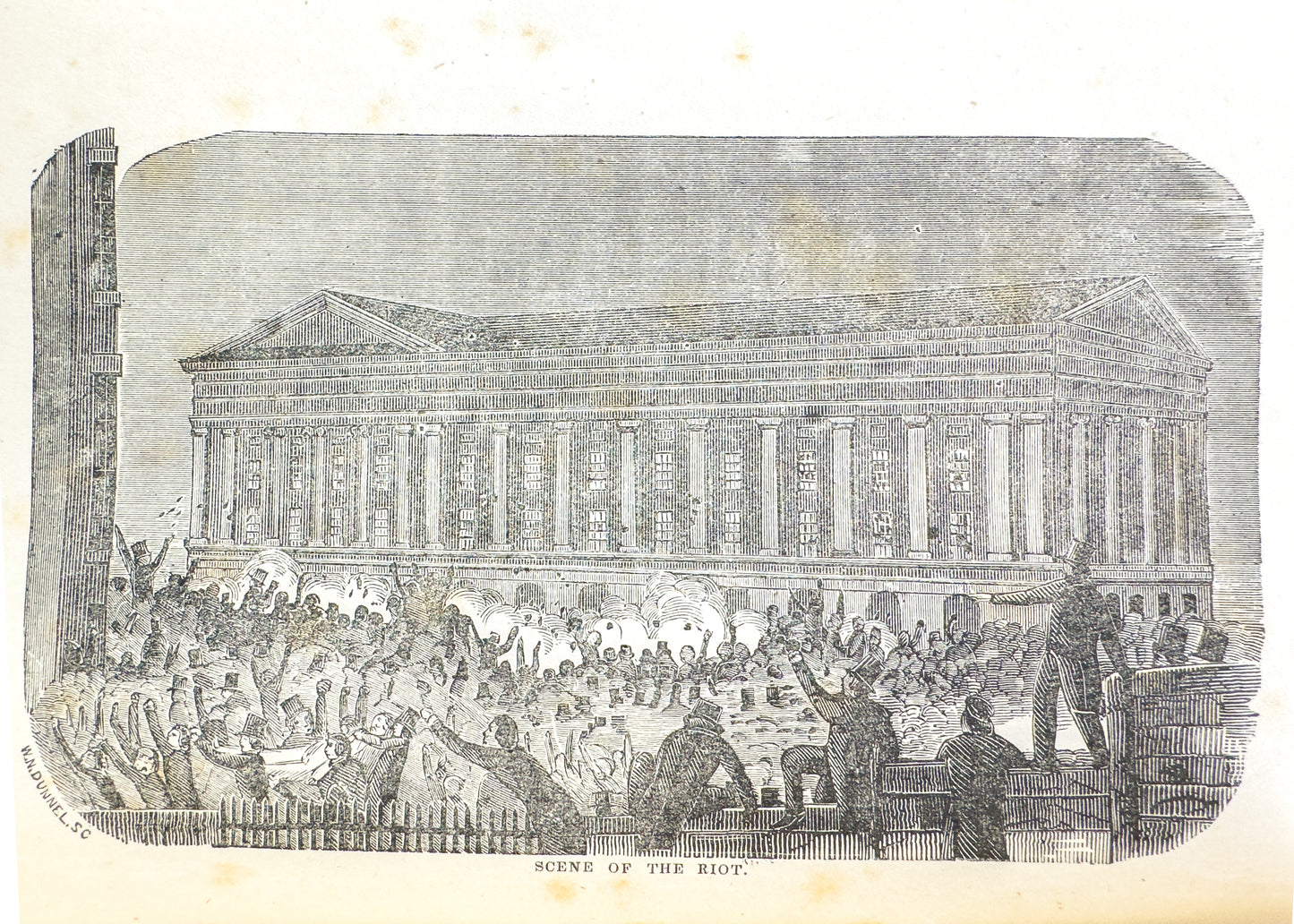

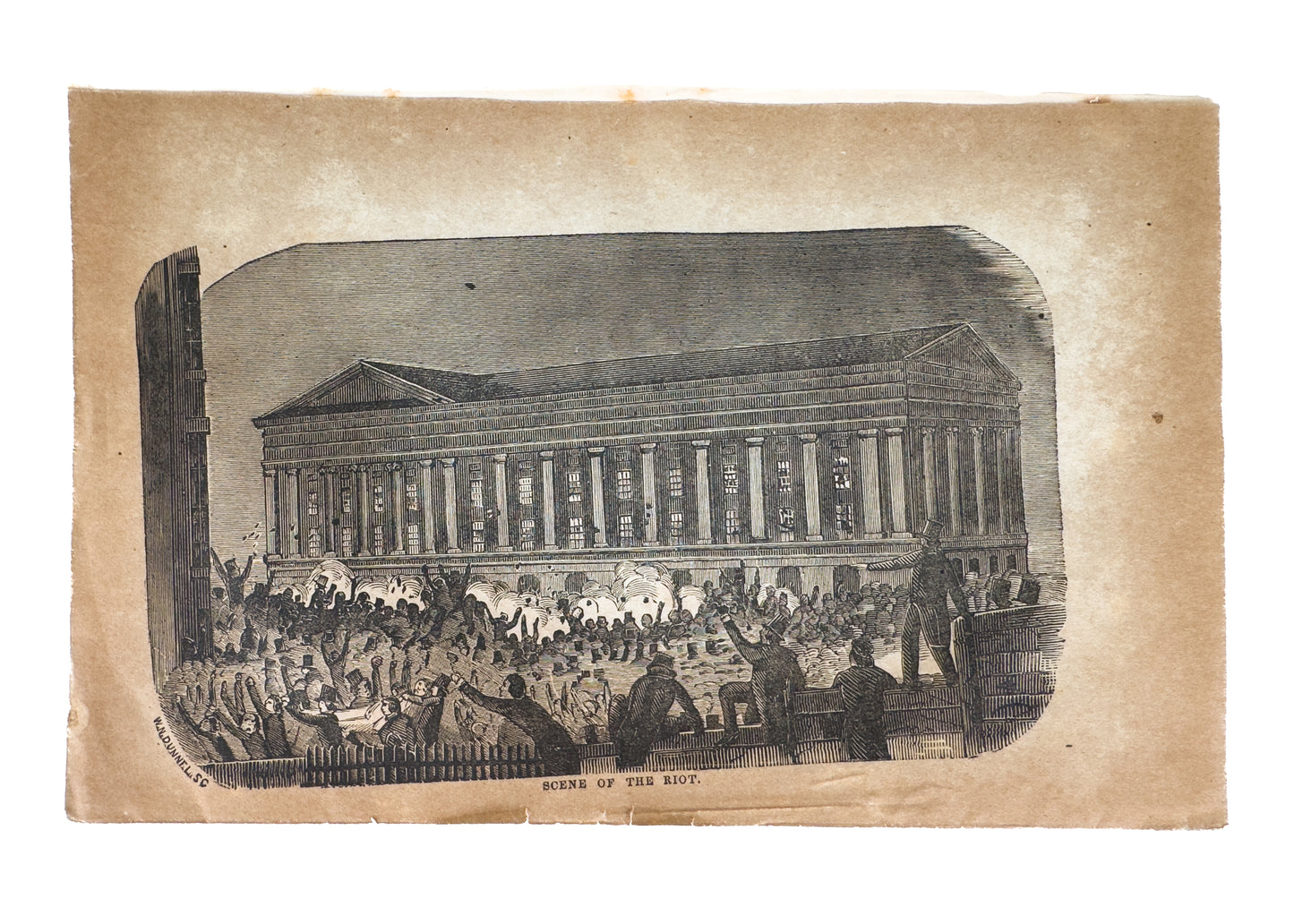

Original wraps, frontis full page woodcut reproduced on final external leaf of wraps. Textually very crisp and clean. Wraps toned. An exceptional copy.

The Astor Place Riot.

The Astor Place Riot was a violent episode involving thousands of people confronting a detachment of uniformed militia in the streets of New York City on May 10, 1849. More than 20 people were killed and many more injured when soldiers fired into an unruly crowd.

The riot was sparked by the appearance at an upscale opera house of a famous British Shakespearean actor, William Charles Macready. A bitter rivalry with an American actor, Edwin Forrest, festered until it led to violence which mirrored deep societal divisions in the rapidly growing city and across the nation. The two thespians were, in a sense, proxies for opposite sides of a growing class division in American urban society.

The rivalry between the British actor Macready and his American counterpart Forrest had started years earlier. Macready had toured America, and Forrest essentially followed him, performing the same roles in different theaters.

The idea of dueling actors was popular with the public. And when Forrest embarked on a tour of Macready's home turf of England, crowds came to see him. The transatlantic rivalry flourished.

However, when Forrest returned to England in the mid-1840s for a second tour, crowds were sparse. Forrest blamed his rival, and showed up at a Macready performance and loudly hissed from the audience.

The rivalry, which had been more or less good-natured to that point, turned very bitter. And when Macready returned to America in 1849, Forrest again booked himself into nearby theaters.

The controversy between the two actors became symbolic of a divide in American society. Upper-class New Yorkers, identified with the British gentleman Macready, and the lower-class New Yorkers, rooted for the American, Forrest.

On the night of May 7, 1849, Macready was about to take the stage in a production of “Macbeth” when scores of working-class New Yorkers who had bought tickets began filling the seats of the Astor Opera House, which had become an architectural icon of the upper class. And the pretensions of its moneyed patrons had become offensive to an emerging street culture embodied by Irish and Italian Immigrants and “Bowery Boys.”

The ruffian crowd had obviously shown up to cause trouble, and did not disappoint. When Macready came onstage, protests began with boos and hisses. And as the actor stood silently, waiting for the commotion to subside, he was greeted with a barrage of rotting eggs.

The performance had to be canceled. And Macready, outraged and angry, announced the next day that he would be leaving America immediately. He was urged to stay by upper-class New Yorkers, who wanted him to continue performing at the opera house.

“Macbeth” was rescheduled for the evening of May 10th, and the city government stationed a militia company, with horses and artillery, in nearby Washington Square Park. Downtown bruisers, from the neighborhood known as the Five Points, headed uptown. Everyone expected trouble.

On the day of the riot, preparations were made on both sides. The opera house where Macready was to perform was fortified, its windows barricaded. Scores of policemen were stationed inside, and the audience was screened when entering the building.

Outside, crowds gathered, determined to storm the theater. Handbills denouncing MacCready and his fans as British subjects imposing their values on Americans had enraged many immigrant Irish workers who joined the mob.

As Macready took the stage, trouble began in the street. A crowd tried to charge the opera house, and police wielding clubs attacked them. As the fighting swelled, a company of soldiers marched up Broadway and turned east on Eighth Street, headed to the theater.

As the militia company approached, rioters pelted them with bricks. In danger of being overrun by the large crowd, the soldiers were ordered to fire their rifles at the rioters. More than 20 rioters were shot dead, and many were wounded. The city was shocked, and news of the violence traveled quickly to other places via telegraph.

Macready fled the theater through a back exit and somehow made it to his hotel. There was a fear, for a time, that a mob would sack his hotel and kill him. That didn’t happen, and the next day he fled New York, turning up in Boston a few days later.

The day after the riot was tense in New York City. Crowds gathered in lower Manhattan, intent on marching uptown and attacking the opera house. But when they tried to move northward, armed police blocked the way. The tension eventually subsided, but the same lines of division emerged again in the Draft Riots of 1863.

Share