Specs Fine Books

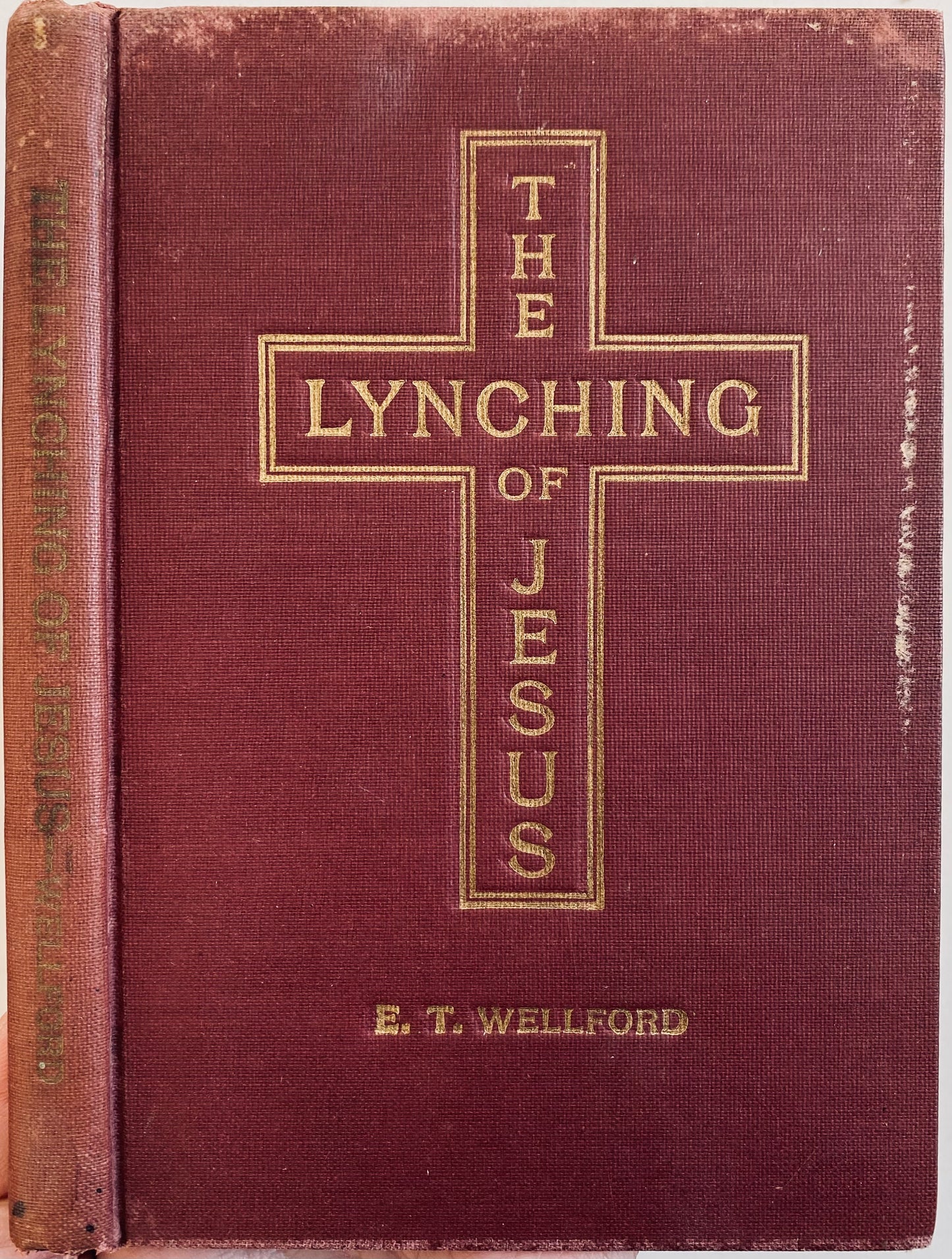

1905 E. T. WELLFORD. The Lynching of Jesus. Exceptionally Rare Autographed Edition.

1905 E. T. WELLFORD. The Lynching of Jesus. Exceptionally Rare Autographed Edition.

Couldn't load pickup availability

Very scarce work on the trial and death of Jesus challenging Americans, especially white Americans, to see the continuity between the ethnically motivated death of Jesus and lynchings in the United States; even those performed under the "due process" of law.

Wellford had a unique perspective on the subject. His father served as a part of the Virginia Judiciary for over 30 years. Virginia had especially aggressive lynching laws; sixty-eight men in the years surrounding this books release were put to death by public lynching. All but 15 of them were black, even though the black population comprised far less than half the total persons in the state. Lynching continued in Virginia until 1955, though it was at its zenith at the time of the present work's publication.

Wellford is considered the first white author to take seriously the theological connectivity between the death of Jesus as an act of disproportionate and racially motivated mob violence and the disproportionate and racially motivated mob [whether formal or informal] violence of the modern lynching. See The Southern Rite of Human Sacrifice from the Journal of Southern Religion, extracted below.

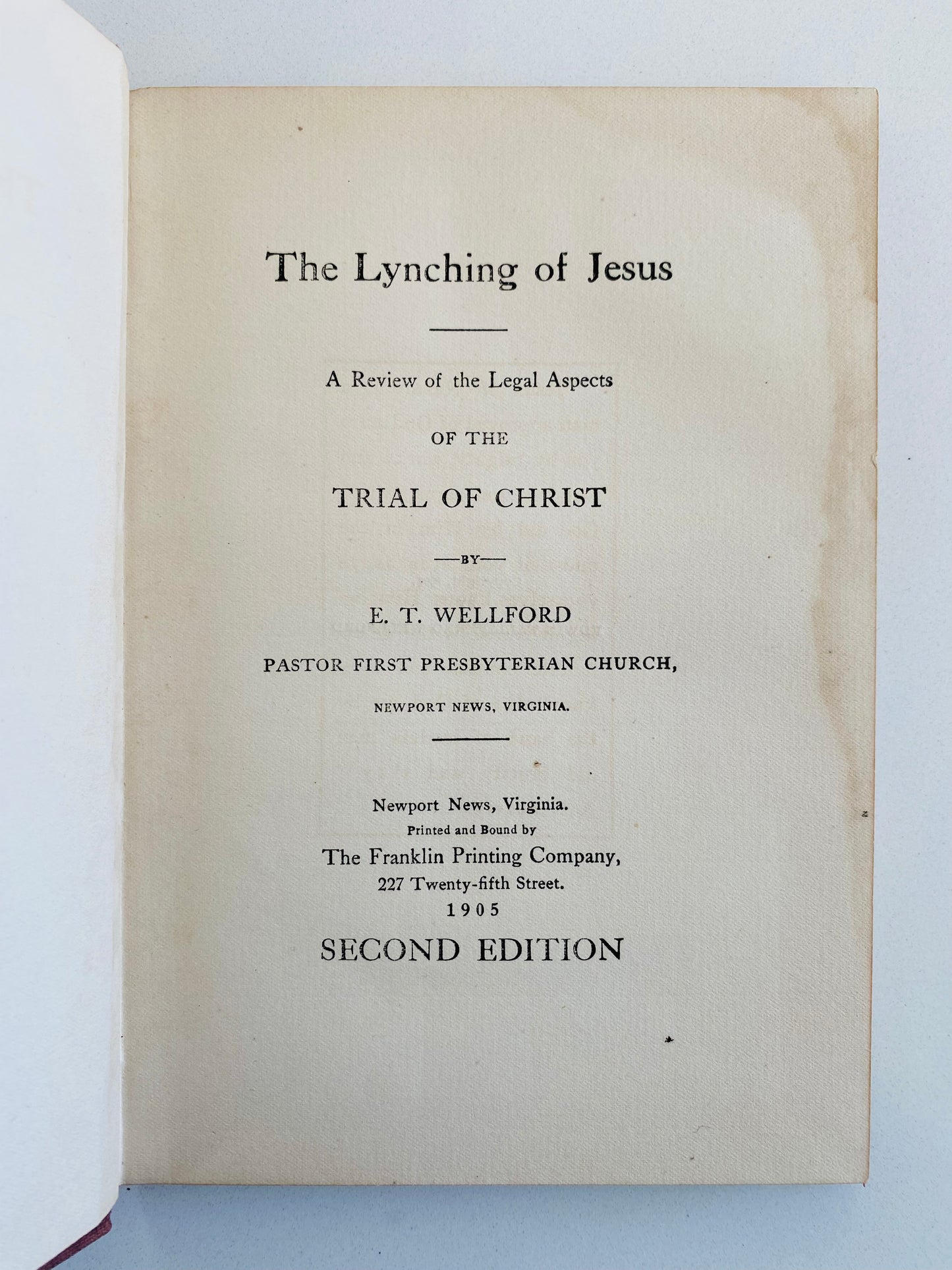

Wellford, E. T. The Lynching of Jesus. A Review of the Legal Aspects of the Trial of Christ. Newport News, Virginia. Franklin Printing Company. 1905. Second Edition.

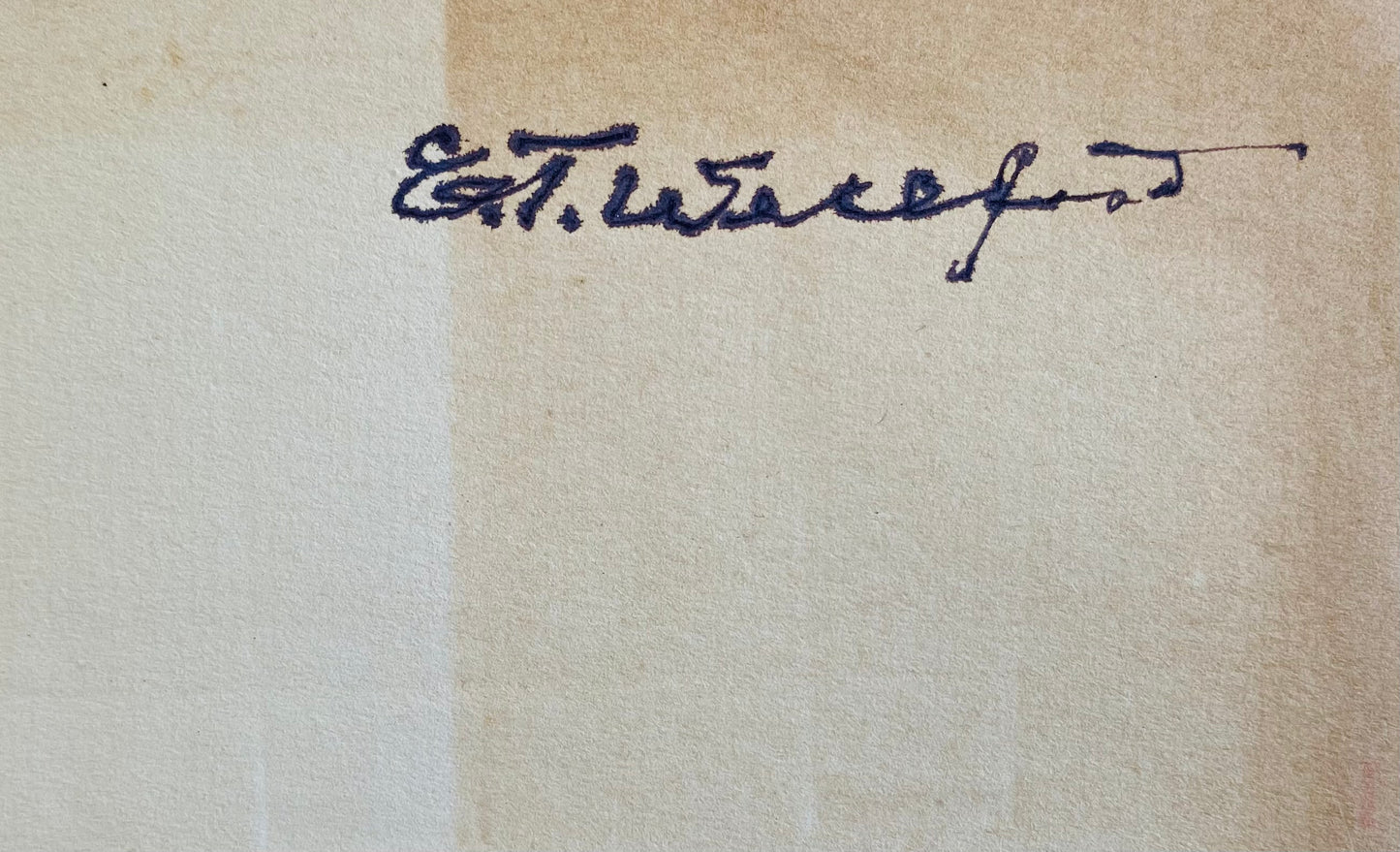

Very solid copy, some light staining at extremities; very minor remainder of dustjacket at extremities. Autograph on blank ffep.

The last copy of this we had sold, not autographed, at auction for I believe $650.00.

EXTRACT:

[In 1905], a strange and compelling little book appeared, written by the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Newport News, Virginia, Edwin Talliaferro Wellford. In The Lynching of Jesus, Wellford did not confront either ancient or modern myth directly; he merely told a familiar story with a reshaded emphasis. His first chapter suggested his purpose. In "The Slaughter of the Innocents" he pointed out that lynching could not be justified by appeal to the myth of immaculate protection; he excoriated mob law as the lynching of both the victim and the law. He thought that the "savage spirit of barbarity" aroused with every lynching constituted a "Reign of Terror" and he pleaded for a "full exposure of the crime" and those who committed it. Then he made an abrupt but sophisticated transition to an even greater barbarity. "The lynching of Jesus excels in brutality and in the slaughter of the innocent, all succeeding offences," he observed to a white Christian audience. "So long as the twentieth century looks on with unstirred sympathy and passes by the mobbing of Jesus with unconcern and apathy, so long will similar deeds be repeated, in any land with impunity. If the public conscience does not resent the greatest it will not take cognizance of the less."

By saying such a thing, Wellford was not diminishing the scandal of lynching black men; he was doing the exact opposite. He was subtly attempting to change the focus of his white Christian readers' attention when they thought of lynching. He wanted them to make a connection between what Christ's executioners did to Him, and what white people did to the black men they murdered. Whereas Robert Lewis Dabney had written fiercely of "God in his punitive providence having punished Christ "legally and righteous for the guilt of sin imputed to him," Wellford now changed the tone and the structure of crucifixion. He was trying to shift responsibility from the black victim of white violence to the white perpetrators themselves; lynching was to be seen not as the [understandable] illegal punishment of guilty black men, but as the modern recapitulation of deicide. In engaging one of the principal doctrines of Christianity deriving from "Jesus Christ and Him crucified," he was thinking of the atonement in a new light. Rather than emphasize the presumed Divine justice involved in Christ's sacrifice, he emphasized its profound injustice; he also seemed to be trying to transfer empathy for the murdered Christ to modern lynch victims by exposing the way in which Jesus had been "lynched". He understood that somehow the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement had allowed white Christians to ignore both the meaning of the crucifixion and the lynching of black men. Wellford did not attack the theology, but instead emphasized the illegality of each step in the process that led to crucifixion.

Leading the reader by the hand through proof texts step by step along the maze through which Jewish and Roman authorities went as they short-circuited the judicial system and avoided due process, the author strips away all pretense to justice. And he insists at last that all participants; Sanhedrin, chief priests, Pontius Pilate and the mob; know that the young rabbi was innocent. "Law," writes Wellford, "was never so debauched, nor `man's inhumanity to man' so apparent." What had murdered the Christ? Hatred, calumny, secrecy, conspiracy, the "insatiate passion of a misguided multitude!" "Innocence," Wellborn observes, "has often been victimized by personal interest, political pull, sordid bribery, or frenzied passion." But he insists, the Nazarene will judge in His time all those who have oppressed, all those who have murdered, for he knows "the merit of right, and has felt the oppression of wrong." The Presbyterian clergyman then ends by linking the reader with the Christ and the Christ, in turn, with victims of injustice; there is no doubt that lynching is the instrument of oppression.

"Religion permeated communal lynching because the act occurred within the context of a sacred order designed to sustain holiness."

Wellford's pamphlet is scarcely the first robin before a spring of either racial justice or theological mutation. But his homiletic insight that Jesus, too, was lynched; when understood within the conservative ethos of Southern white religion; suggests that a few people at least were beginning to see things which such pious and decent men as Atticus Haygood and William Northen could not see. The mythic sustenance of scapegoating available in traditional theology was being challenged.”

Share