Specs Fine Books

1921 THEODOR GEISEL, aka Dr. Seuss. The First Drawing, First Cartoon, and First Poem He Ever Published!

1921 THEODOR GEISEL, aka Dr. Seuss. The First Drawing, First Cartoon, and First Poem He Ever Published!

Couldn't load pickup availability

An irreplaceable grouping of "firsts" by Theodor Seuss Geisel [1904-1991], or Dr. Seuss, the best-selling children’s author of all time. Combined, his works have sold nearly 1 billion copies and have been translated into dozens of languages.

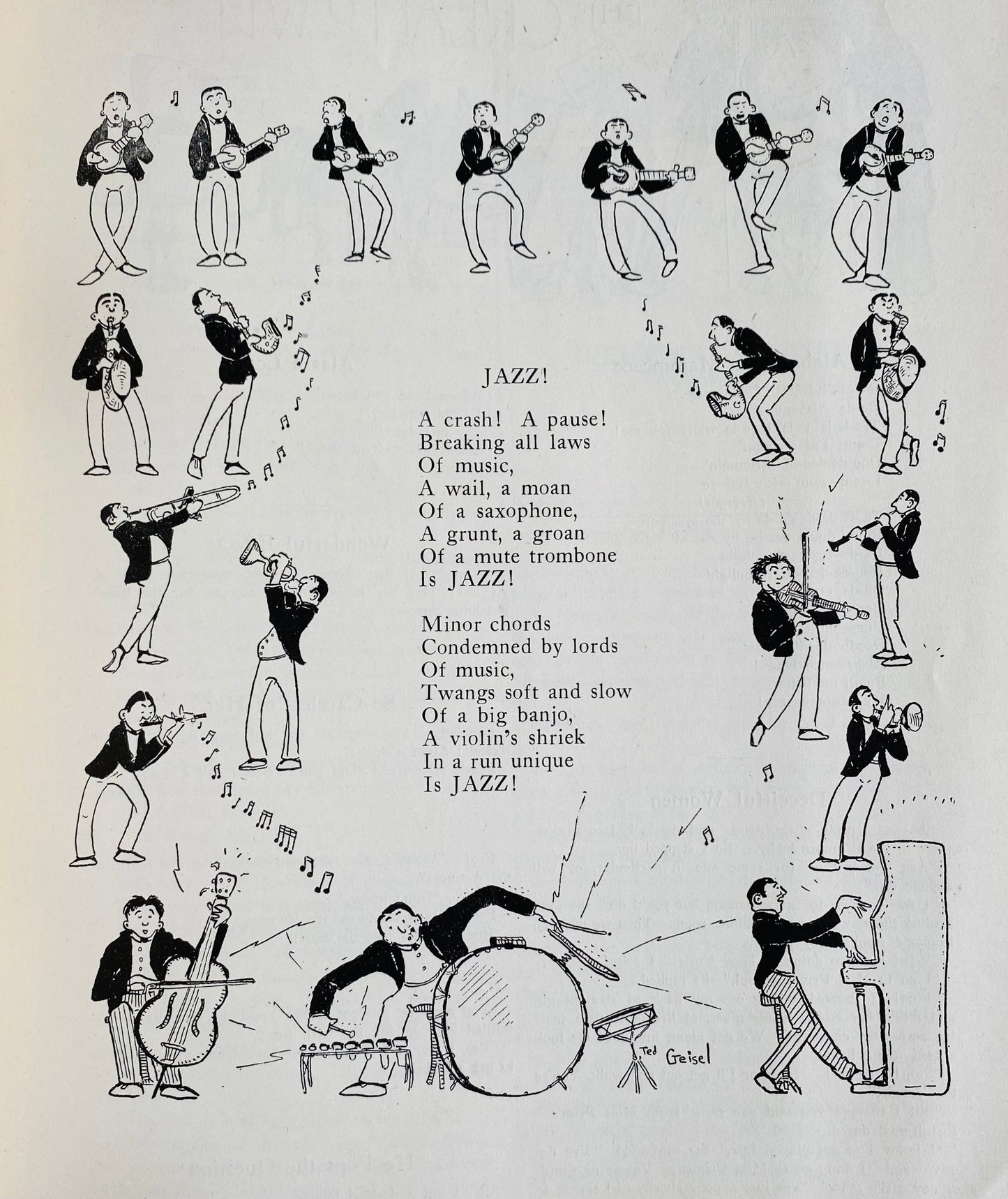

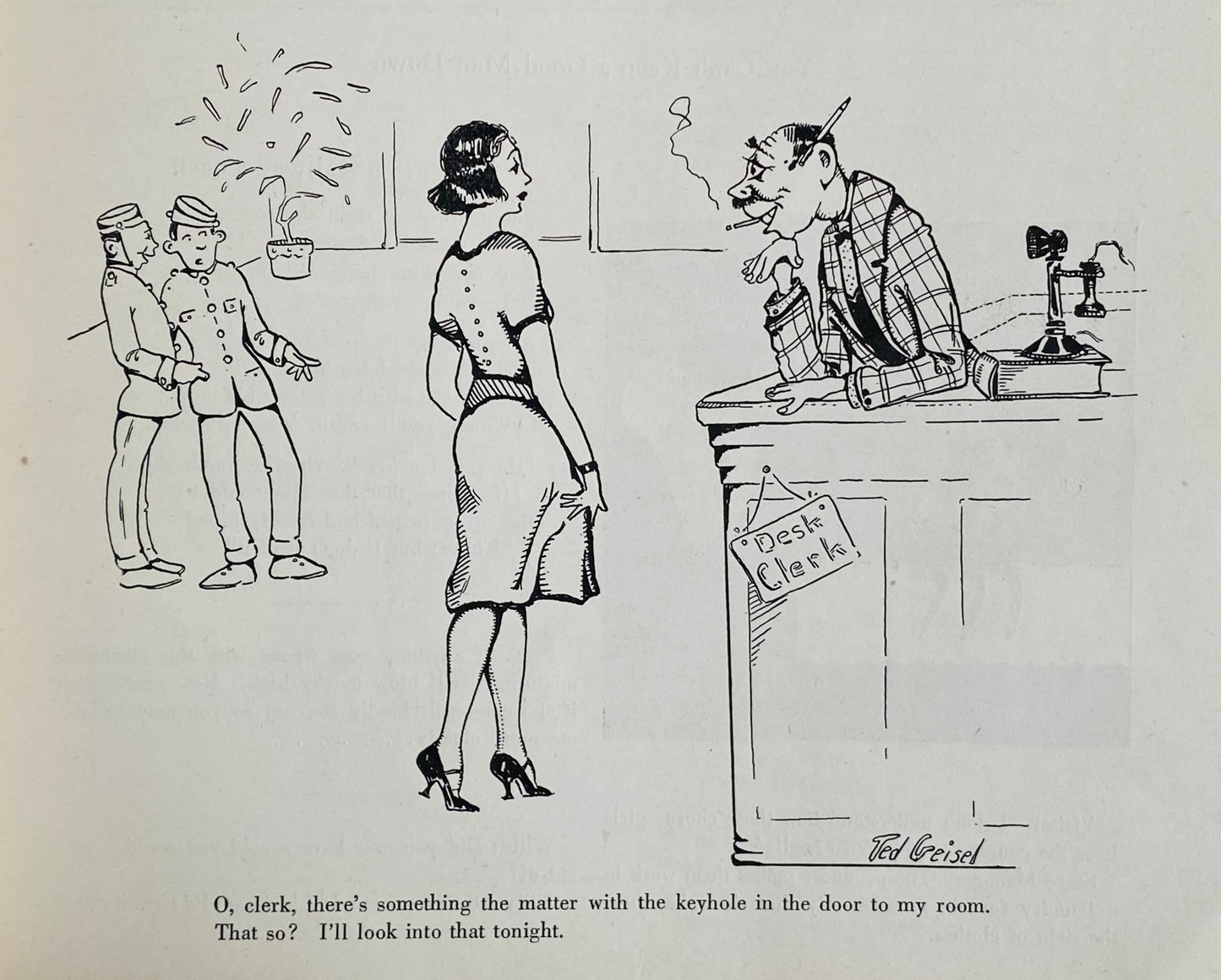

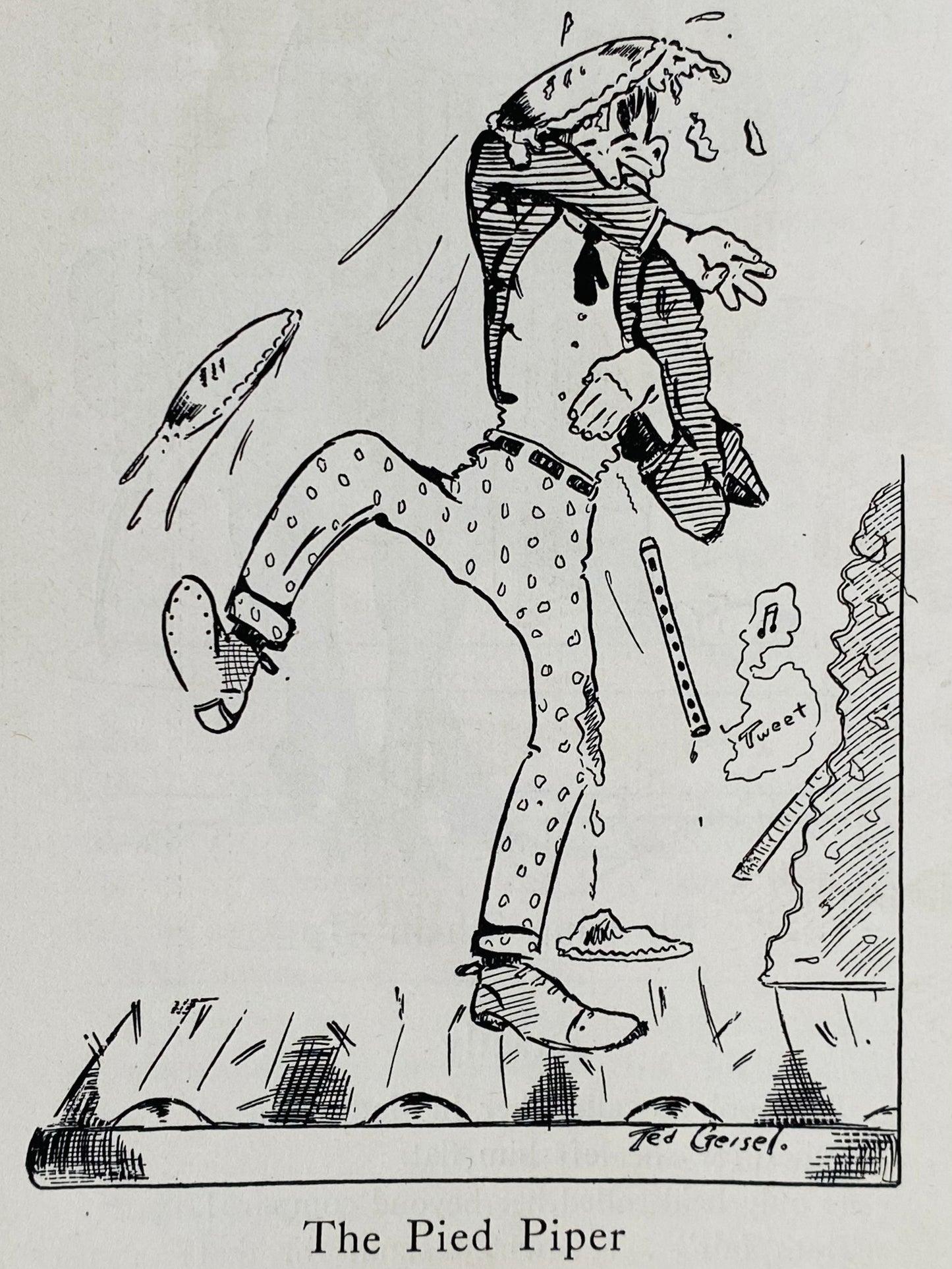

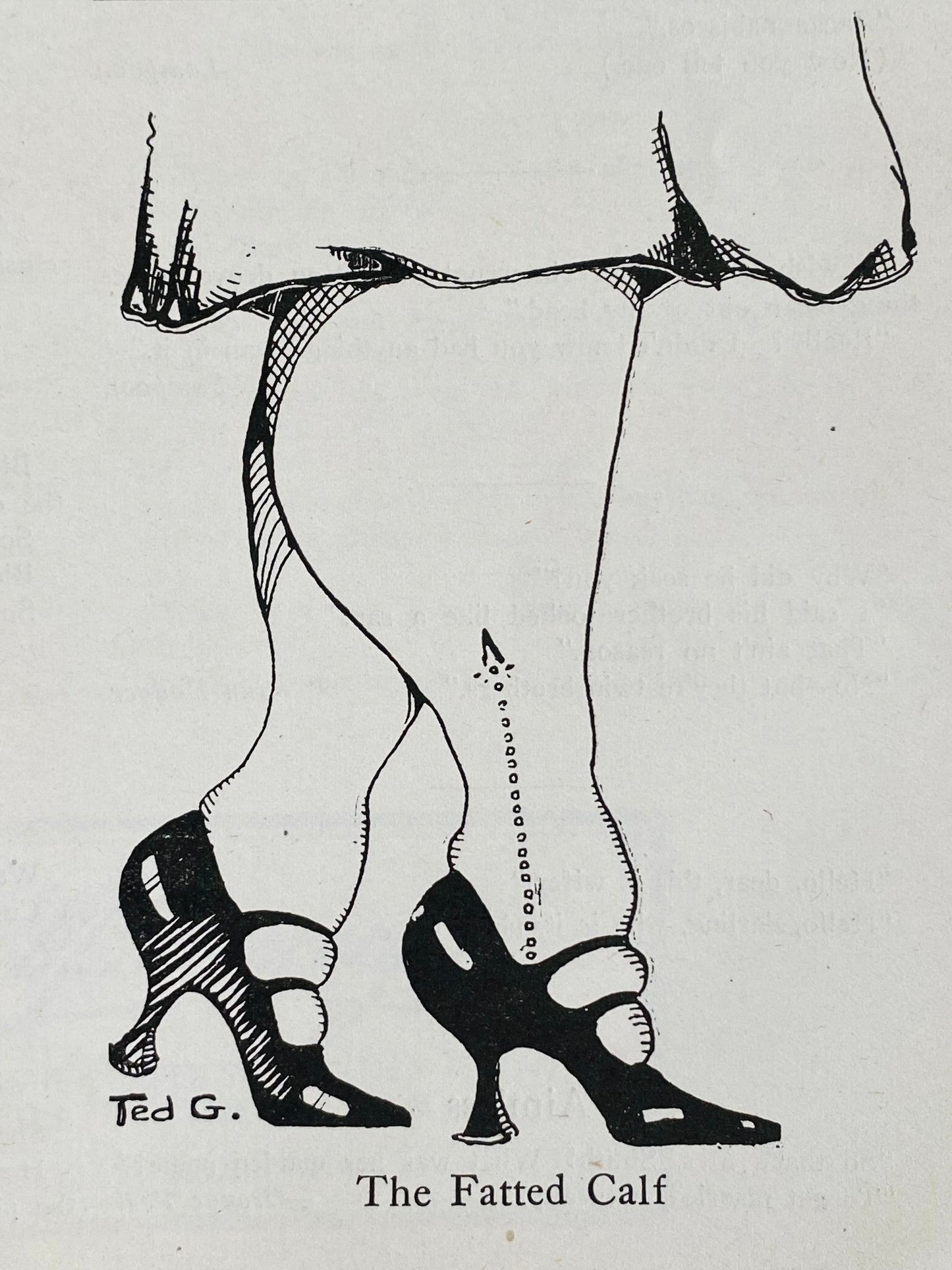

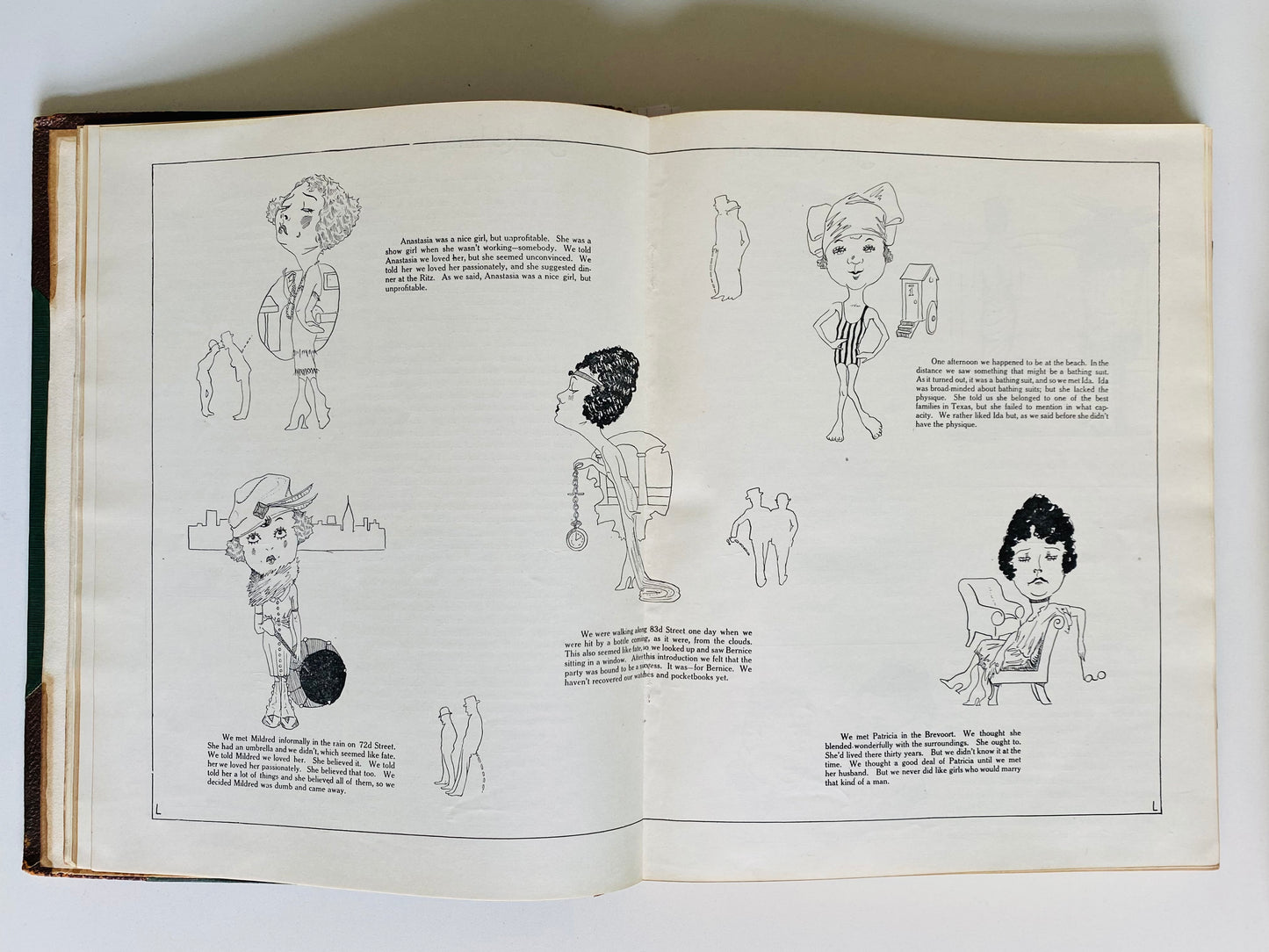

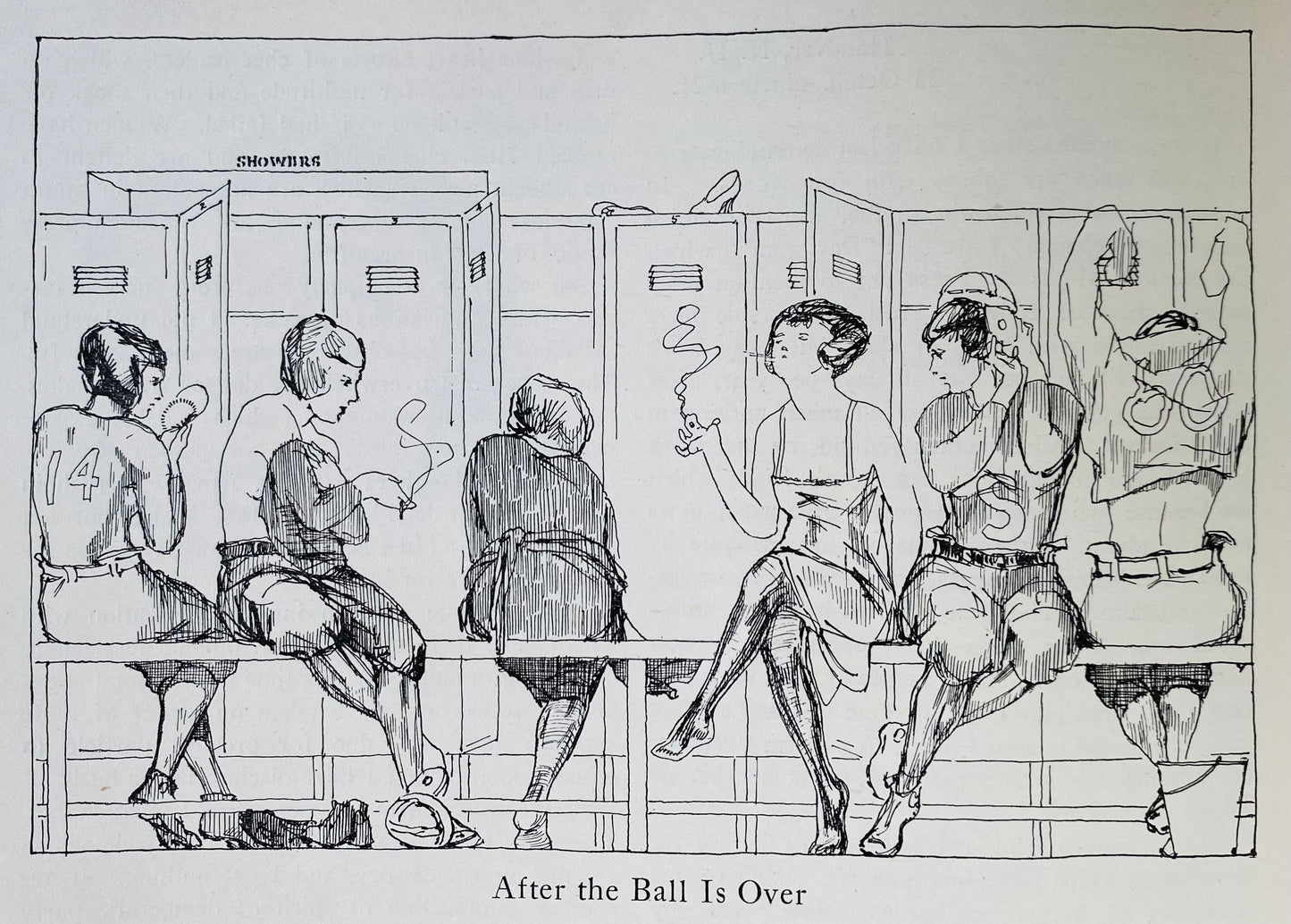

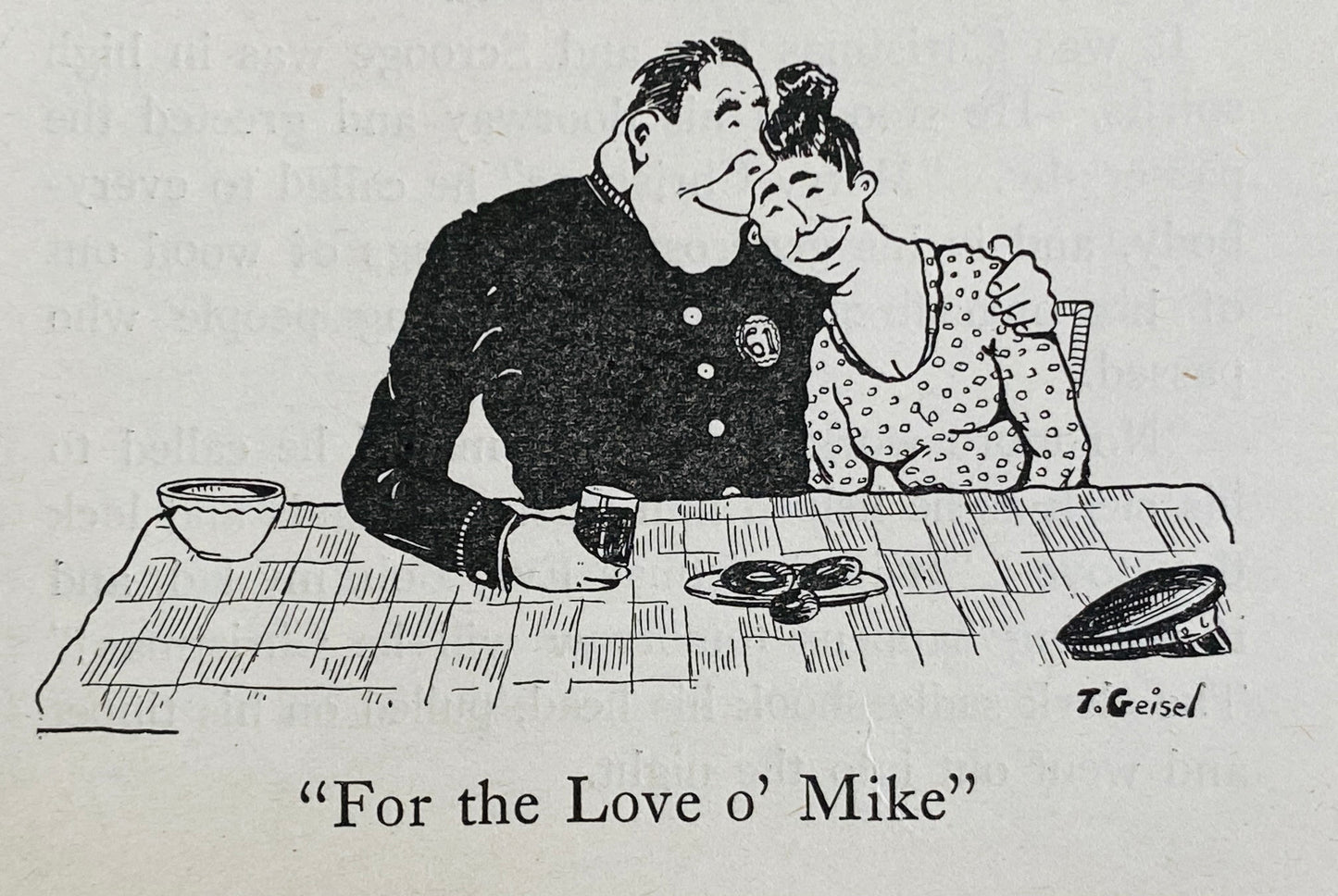

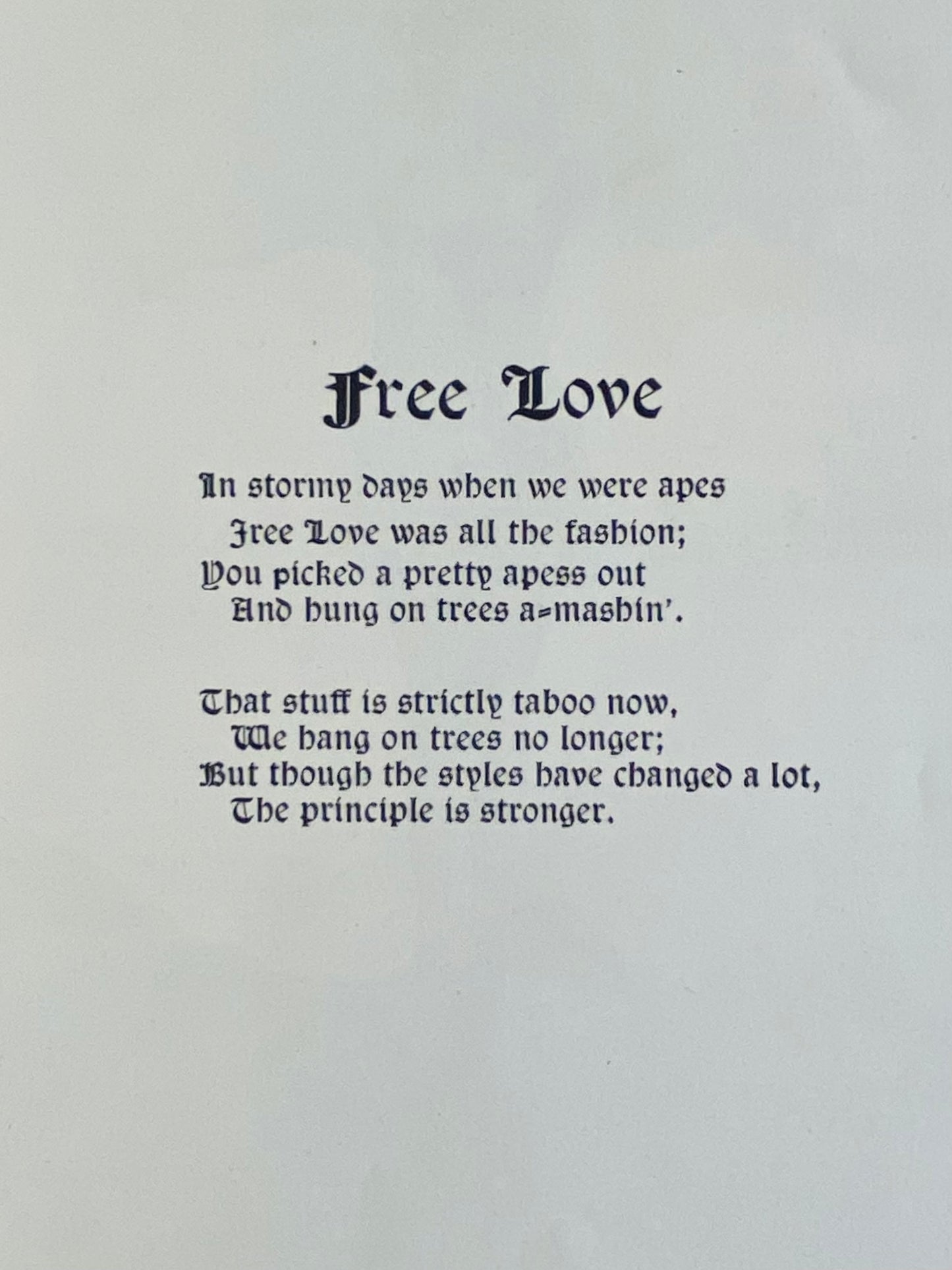

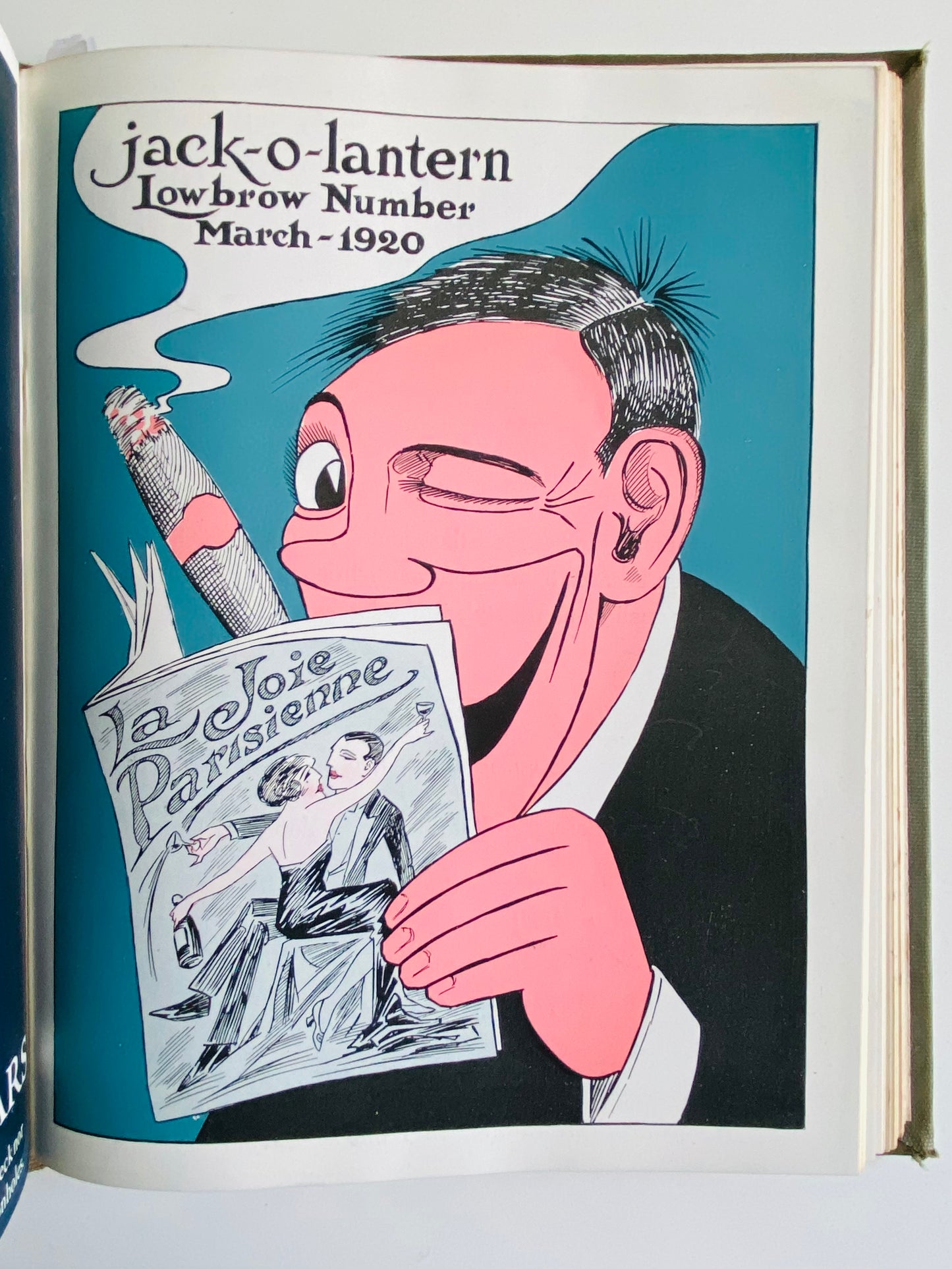

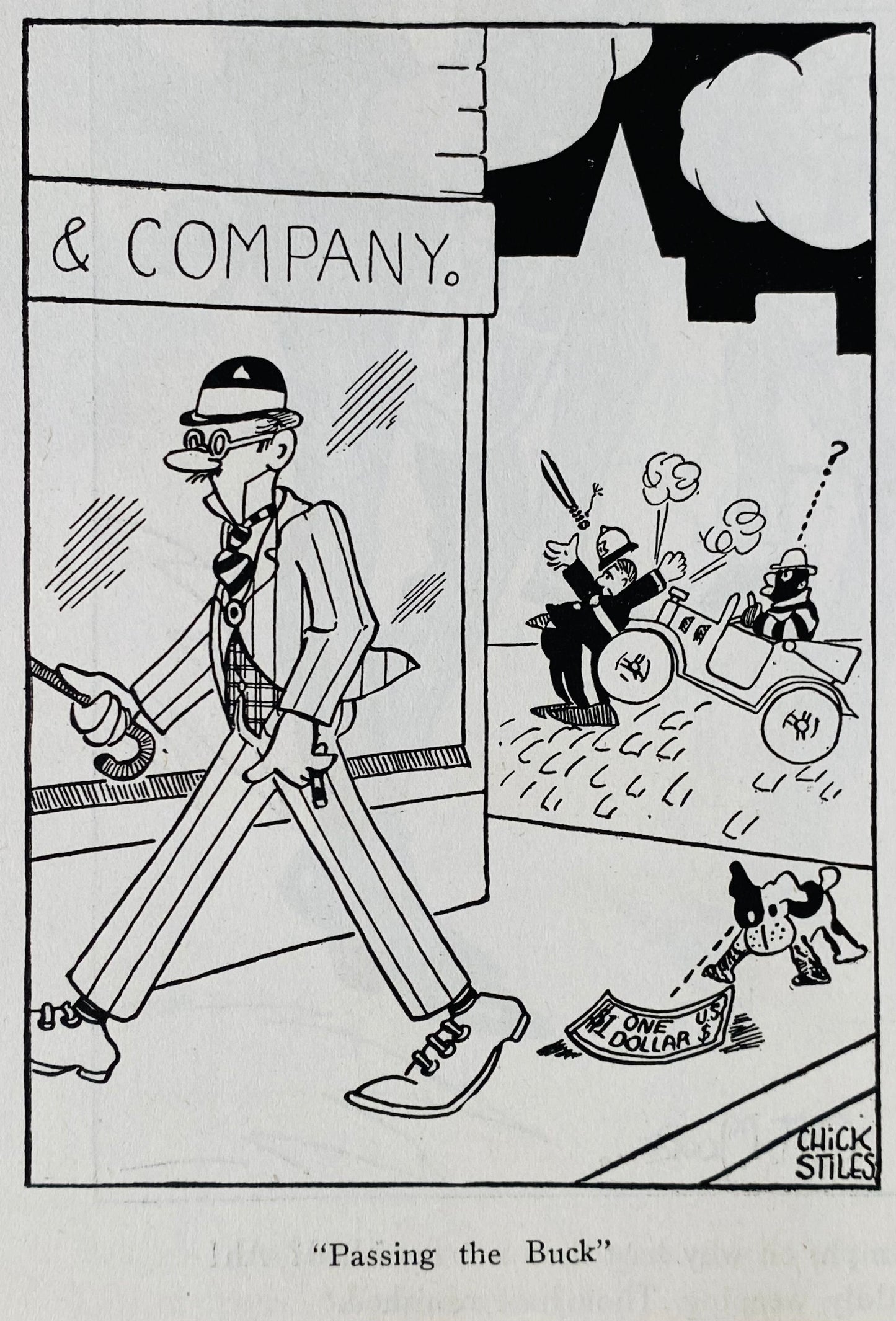

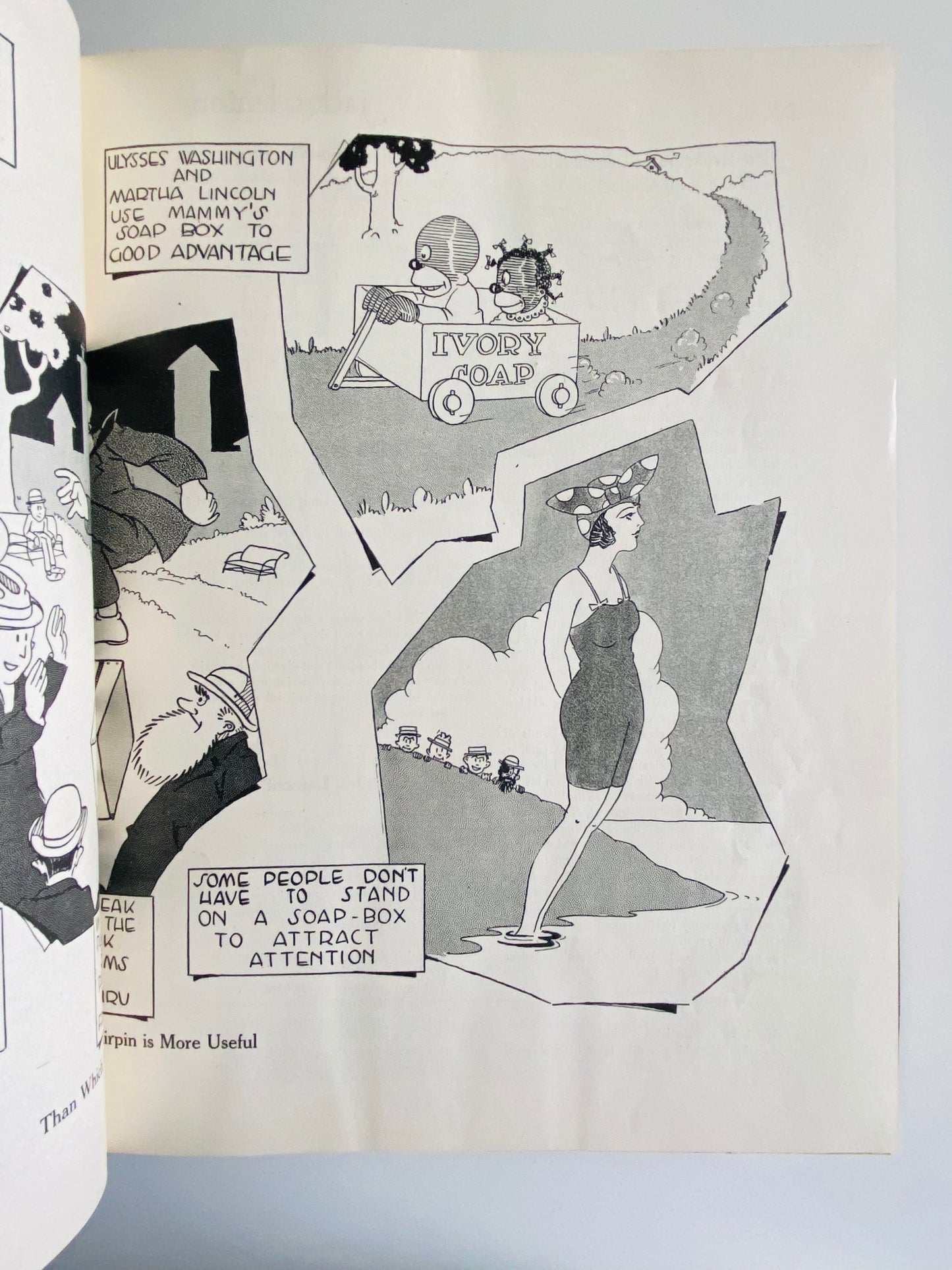

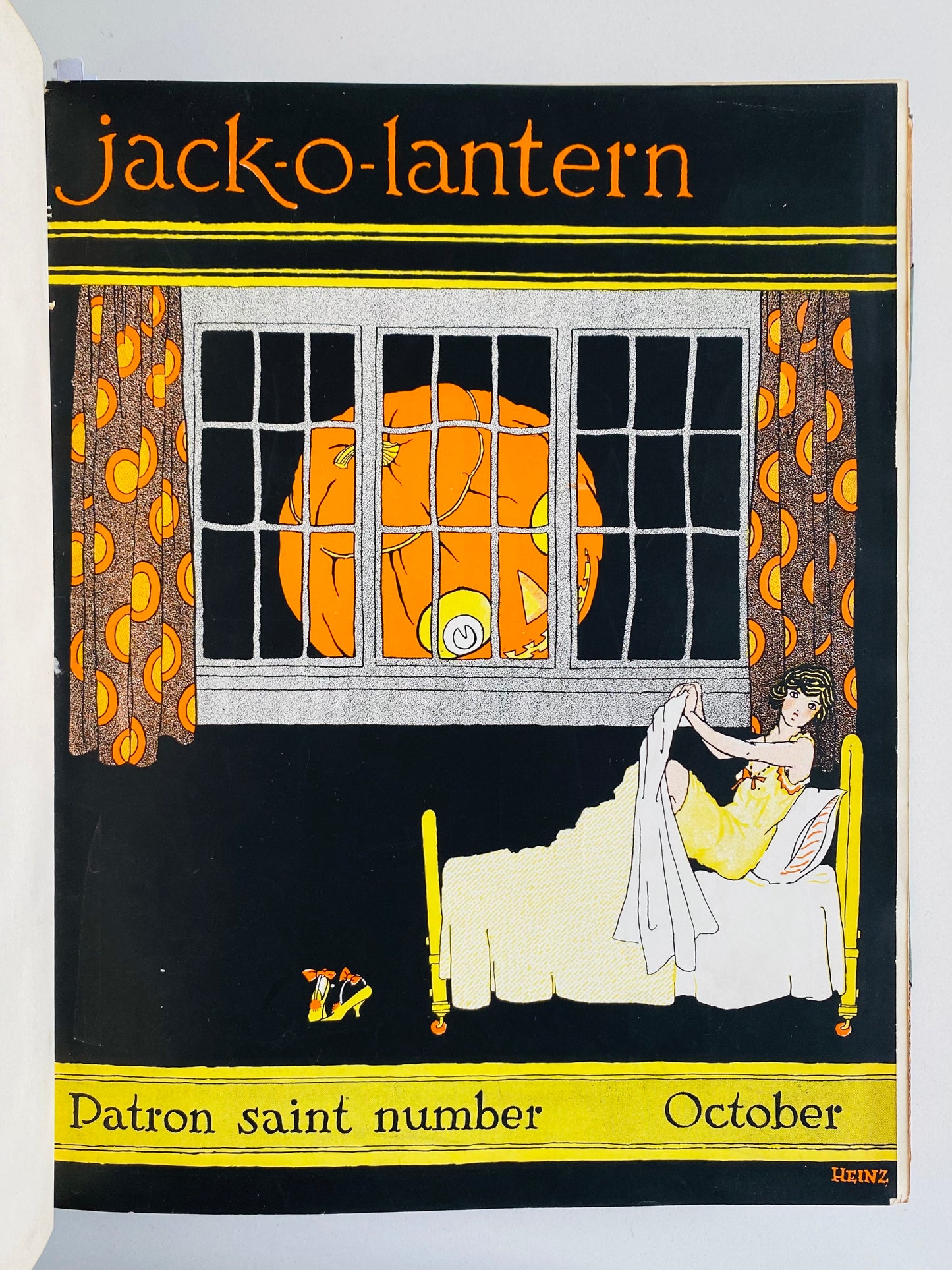

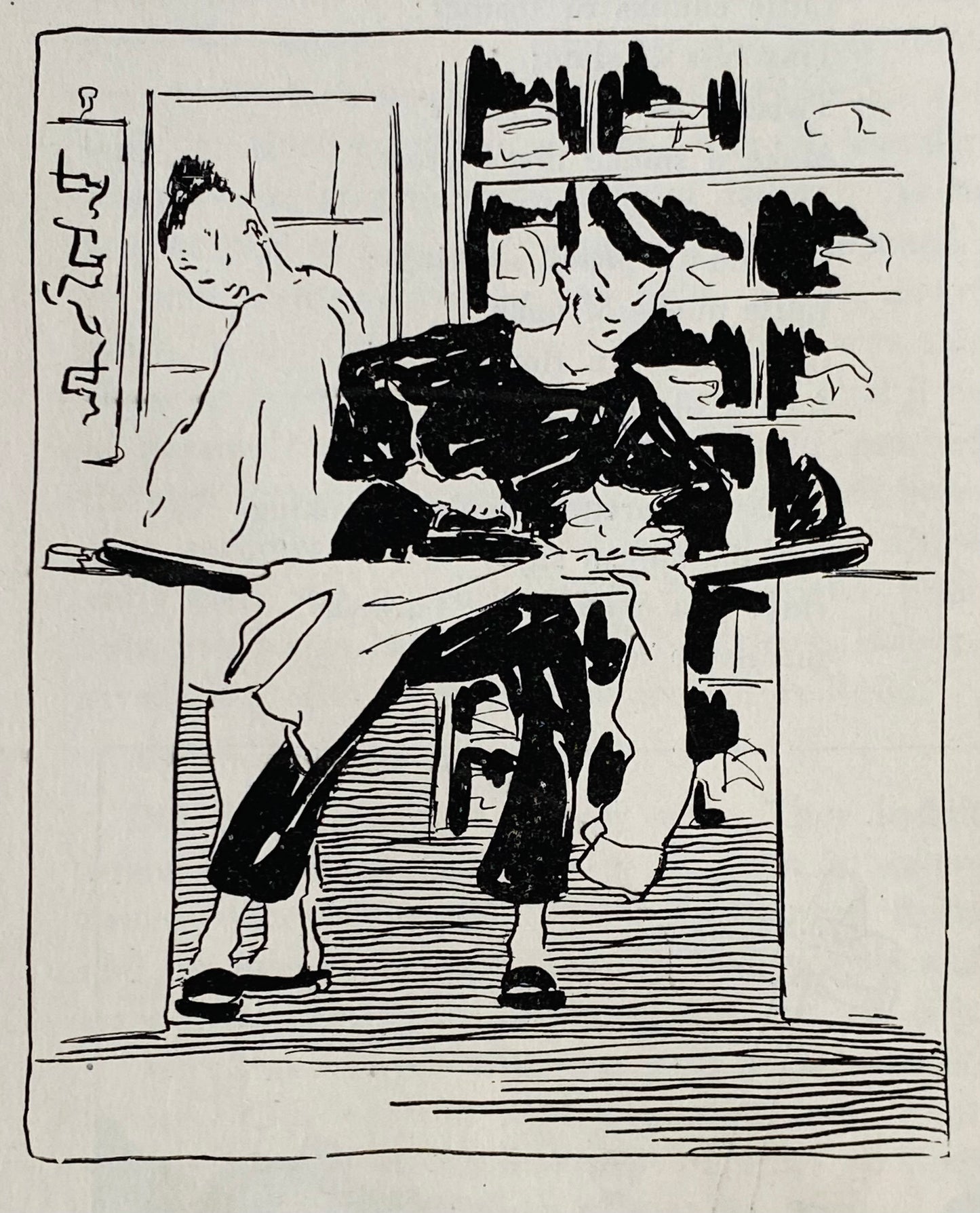

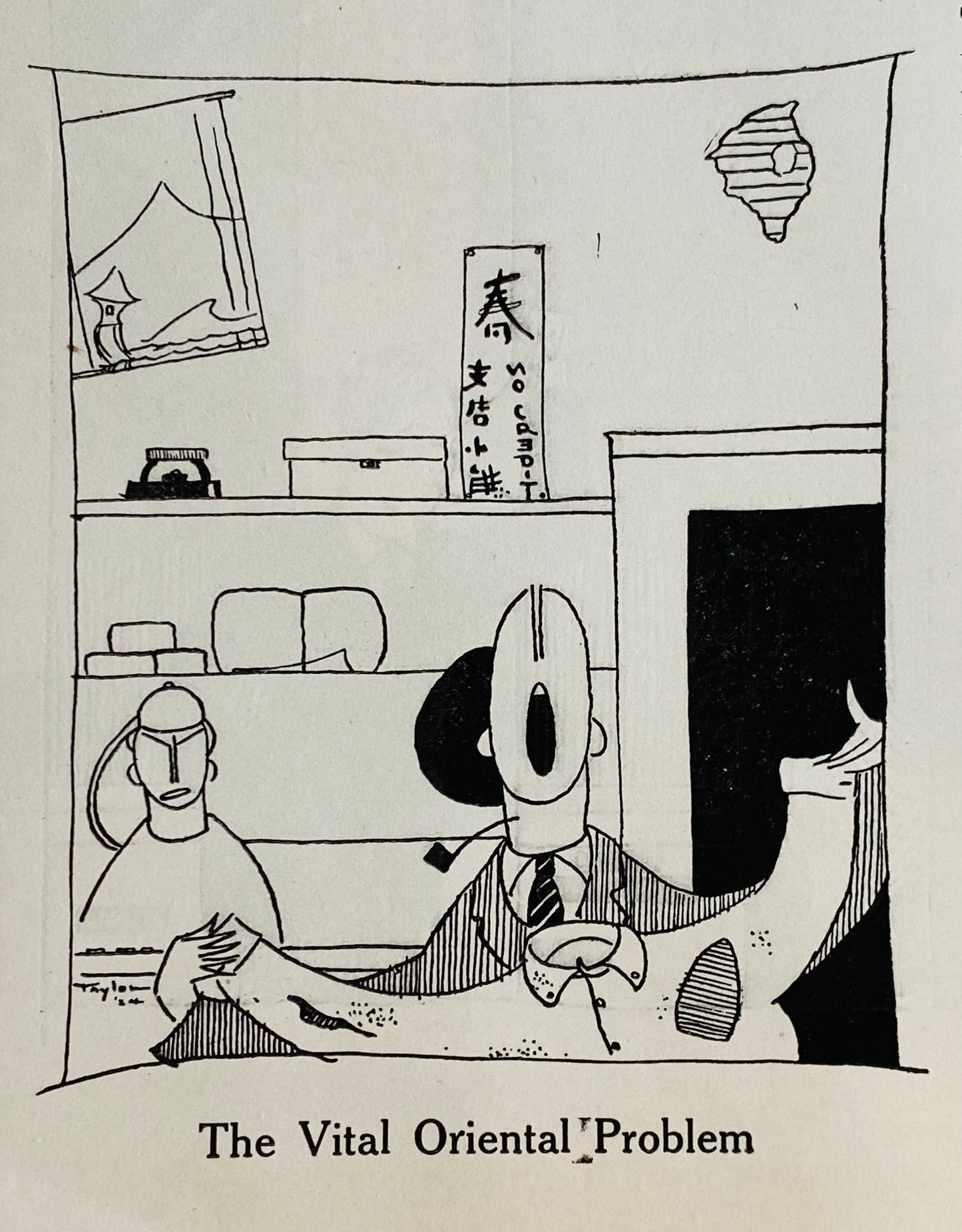

The present grouping of important published documents, comprised of three complete years of Ye Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, include what Theodor Geisel’s first ever formally published drawing [Image #4 in this listing], his first ever formally published cartoon [Image #3 in this listing], and his first ever formally published illustrated poem [Image #2 in this listing]. The latter of these would of course go on to become signature Dr. Seuss, i.e. elaborately illustrated, linguistically inventive poetry.

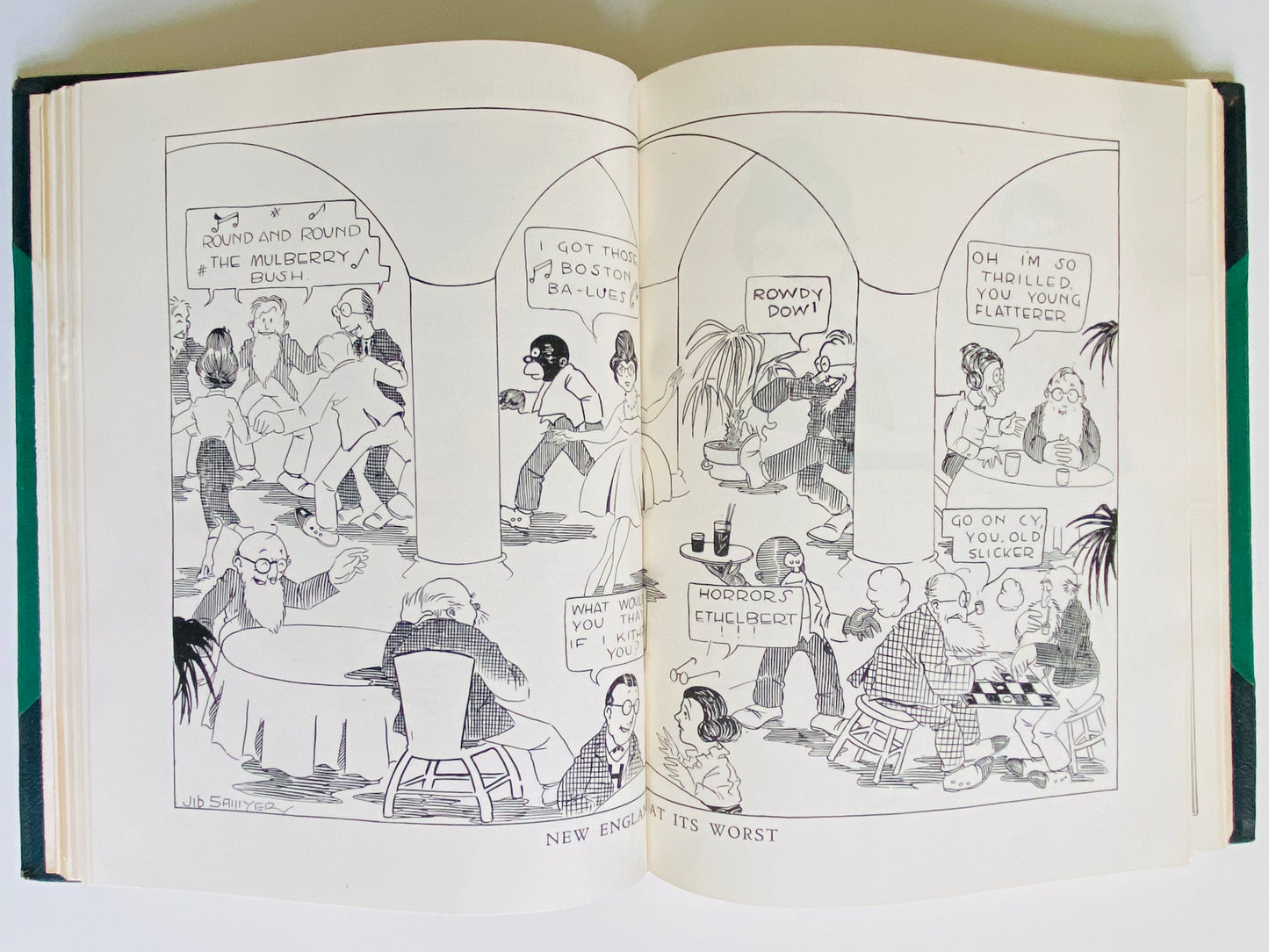

Additionally, these three complete academic years give us a glimpse of Dartmouth as an creative backdrop and formative environment for Geisel’s early development as a person and as an author.

Geisel entered Dartmouth in 1921. It was mere weeks into the semester before he had volunteered himself as a contributor to the college’s humorous magazine, Ye Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern. Previous to this, he had written a play in high school, which he performed himself . . . in blackface. He also had some doodles and bits run off in his high school circular. But these were his first real, “it’s published, and people actually paid for it” works to ever hit the press. And he liked it.

The Ted Geisel to Dr. Seuss path would not be short or without diversion though. That was probably a good thing. He seems to have been quite an under-developed as a person early in life. Before the end of his first year, he had been removed from the periodical’s contributing staff. It was Prohibition [the pages are full of anti-Prohibition content] and he decided to throw a gin party with nine friends in his room. When it was discovered, he was booted from the magazine. He was also a lackluster student and voted “least likely to succeed” by his fraternity.

Still, drawing and writing were constants. Those he could and did work at.

Before being formally removed from the magazine’s list of contributors, he was able to have published nearly an entire year's worth of original drawings, cartoons, at least one poem. These are all present here in the 1921-1922 volume. He likely contributed to some other written works sans name in these pages as well*

His ban was also the event that led to his emerging and now culturally ubiquitous moniker. As a work-around during his period as a black-listed contributor, he continued to submit material to the periodical using only his middle name, Seuss, without the administration’s knowledge. It stuck. By his senior year, in 1925, he had long been back in favor and had become Ye Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern’s Editor-in-Chief.

He still had definite room to grow as a person. After graduation, somewhat aimless, he told his hard-working father he had been given a scholarship to continue his studies at Oxford. Why is unknown. It seems Geisel was “truth-averse” at various points, even into adulthood. Predictably, it backfired. His father was so proud of his son's news he had it published in the next day’s paper. When it came out, Geisel’s father, a man of slender means, saved, borrowed, and begged to raise the money to send him to Oxford anyway. He enrolled in the Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature program, intending to become a teacher. He dropped out, still doodling. His new love-interest convinced him that was where his future was, doodling. He began submitting cartoons to Vanity Fair, Life, and anyone else who could pay him for his work, including advertisements for Standard Oil, etc.,

1937 was the break though, creatively anyway. He had been successful in advertising and cartoons prior to this. But it was then his first significant, distinctly “Seuss” published work appeared, And to Think I saw it on Mulberry Street. It was immediately successful. But the War demanded all hands on deck, including illustrators and animators. From 1940-1945, he was almost entirely occupied with creating political cartoons, advertisements, recruitment material, etc., for the Federal Government.

It seems ironic that mass media, oil companies, and the war apparatus were early employers. It was perhaps there, on the inside of those organizations, that he developed his later counter-cultural or culture-critical stances on the power structures of society.

After the War, it was back to the children’s books. He had found his pen’s proper paper in 1937 and jumped back to it with gusto. A steady stream of classics emerged, including If I Ran the Zoo (1950), Horton Hears a Who! (1955), The Cat in the Hat (1957), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1957), Green Eggs and Ham (1960), and so on. He never stopped.

He seems to have developed as a person as well. While Seuss, in his own words, never set out to write books of ethics or morals, he was a "strongly-viewed" person, and those views rather naturally worked their way into his writings. We might say his works were not intentionally books on ethics when each began, but by final draft, they were certainly self-consciously ethical tales.

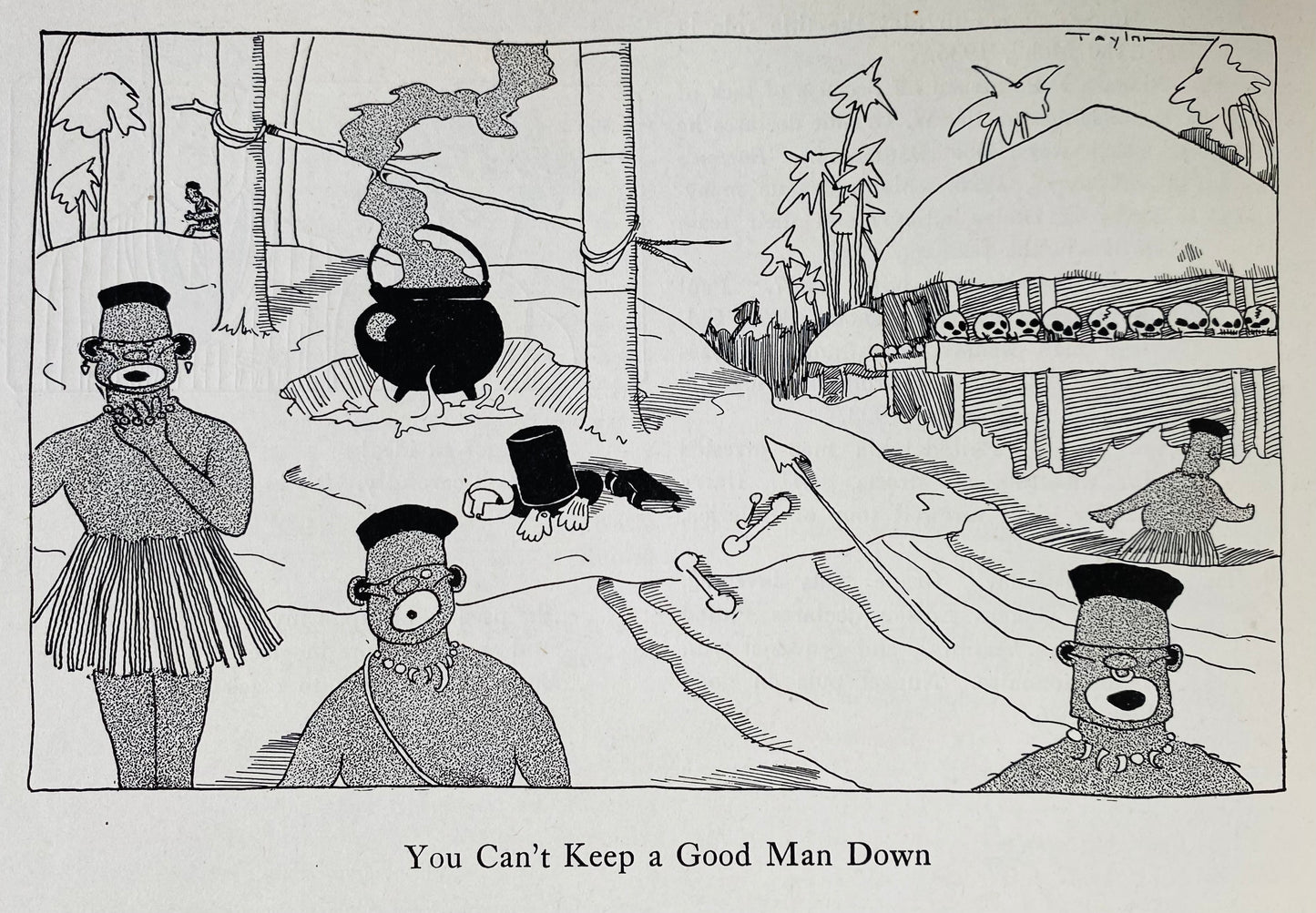

As has been noted in recent public coverage, and as we have already alluded to, Seuss didn’t begin as the culturally moralistic, whimsical writer we find him to be in his beloved children’s books. In my view, it would also be dishonest to say he was simply a man of his times. As a young man, he held views about race and about women that were transparently known to be misogynist and racist, even for the 1920’s**. What we find as background in the present volumes helps illuminate his thought-world on women and race, but he himself exceeded even these.

His views, already present to some extent as evidenced by his “blackface” incident, would only have been reinforced at Dartmouth. The Ivy League school was fully segregated until later in the 1920's. Rather transparent racism was considered the norm in a wealthy, privileged, and almost exclusively white institution. See here.

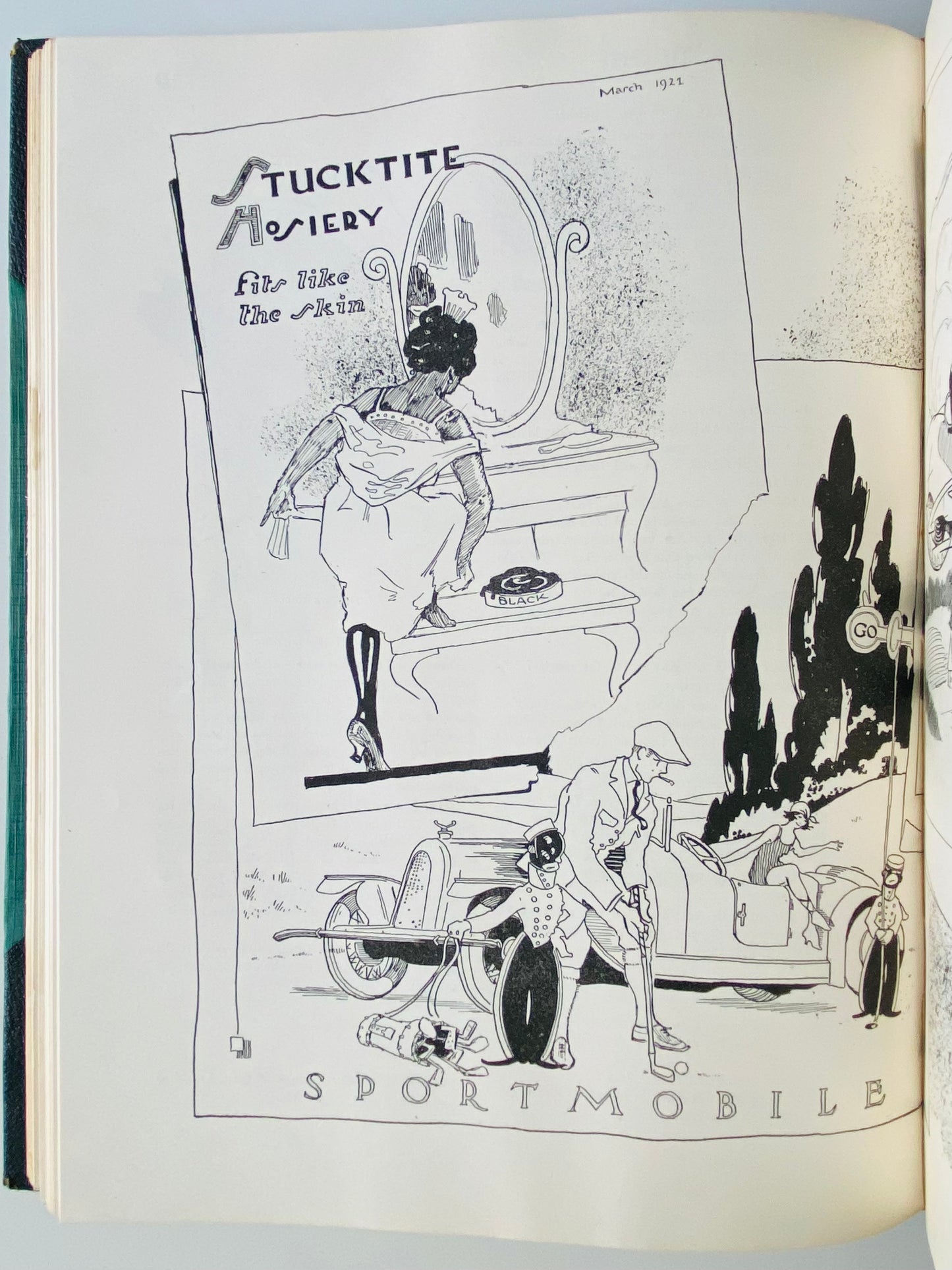

Flitting through the pages of Ye Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, it is evident female diminishment and objectification were also staples of the local humor [See images 3, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 16, 21, and 24 in this listing]. This was the writing world Theodor blossomed in. He shared soil with the other Jack-O-Lantern boys [they were all men]; he drank with his co-writers, and we are told spent nearly all his free time with them. And sure enough, Seuss joins in with a not so female-friendly contribution of his own. It appears to be his very first published cartoon in any formal setting [See image 3 in this listing], a full six years before his first nationally published cartoon appeared in the July 16, 1927 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Seuss would also later create both text and art that more deeply embodied the objectification of women [see The Seven Lady Godivas here ]

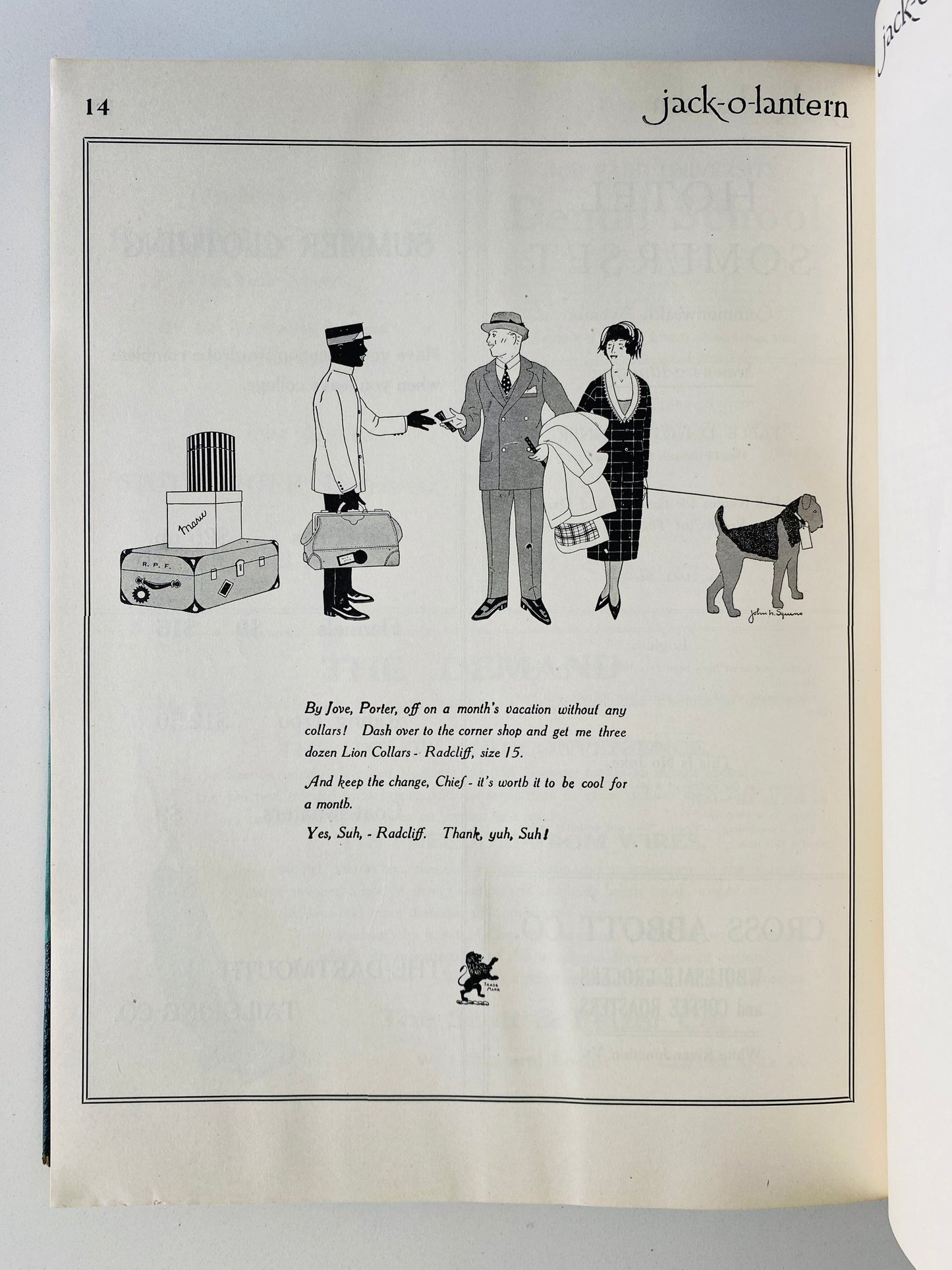

If women are objectified and the source of humor in the pages, racism and racial insensitivity are evident as well. This was aimed at black Americans [See images 11, 15, 17, 18, 19, 22, and 23 in this listing] and an entire issue devoted to Asian characters [See images 25, 26, 27, 28, and 29 in this listing for examples].

Seuss’ racial insensitivities weren’t limited to black Americans or to the pages of Ye Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern. Seuss vocally and rather callously described his support of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. But something changed. It seems to have been immediately after the War that his views on the environment, war, race and global citizenship, and women began took a pivot.

Horton Hears a Who was written as an allegory of America’s post-war occupation of Japan, a sort of recalibration of their human value. The post-War was a new era, one with a new and improved Dr. Seuss who cared about a good many things.

And what we learn in Ye Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern certainly wasn't all negative. In these early efforts, in an open, creative environment, we see glimpses of the soon and coming Seuss. He may be a long way off in conviction and content in these pages, but in style and diction, in artistic direction . . . he is already present and in motion.

The volumes are littered with illustrations evocative of the time; some clean and crisp, others art nouveau inspired. But Ted Geisel’s [as most are signed] jab you in the eye and shout, “Hey! Look at us! We’re different. We’re fantastical! Like nothing you have ever seen before!” Already, his imaginative lines are taking on a life of their own. We have to wonder if he looked at those little drawings and muttered something like, “Oh, the Places You’ll Go.”

When we began reading through the volumes, we knew the illustrations were there. That has been long documented. But the most exciting moment of cataloguing for us came when in the next to last issue of 1921-1922. There it was. JAZZ! A full-page illustrated POEM by Theodore Geisel. I find no trace of this poem in any of the literature. It appears to be his first formally published example. Even more importantly, well, just read it!

He’s there . . . not quite mature . . . not in all his glory . . . but he is there. The sounds, the meter, the language forcing you to experience the poem as an event. Oh yeah. He’s there.

And then there is the subject. Many Seuss scholars have noted the impact of the emerging jazz scene as a source of stylistic inspiration for Seuss. To find his very first published poem to be an interplay between one of the cultural developments that inspired his style and his own style attempting to reflect that cultural moment, . . . how wonderful! This important discovery enhances our understanding of Dr. Seuss’ early sources of influence and inspiration, and all but confirms the early Seuss – Jazz connection.

A first edition of And to Think I saw it on Mulberry Street in fine condition can fetch $15,000 - $20,000. The present, aside from being an important archive of environmental information, contains Seuss’ first published drawing, his first published cartoon, and his first published poem . . . and it’s a doozy.

We trace no other similar material offered at auction, very few institutional issues, let alone bound volumes, and some of this material not even located in the most advanced Seuss scholarship.

Two volumes bound in half leather, rubbed, some fading to spines. The second bound in buckram. The first volume has a few adverts excised without impact to text or content. Very solid, absolutely crisp and clean.

.

.

.

*See here for the haphazard way in which articles were written at the time. Even some drawings by other artists have two sets of initials attached to them. Geisel's all have his name only.

**For a fascinating little interview with the author of a whopping 476pp biography of Dr. Seuss, see here.

Share