Specs Fine Books

1968 MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. Important Large Scale Painting on the Death of MLK Jr.

1968 MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. Important Large Scale Painting on the Death of MLK Jr.

Couldn't load pickup availability

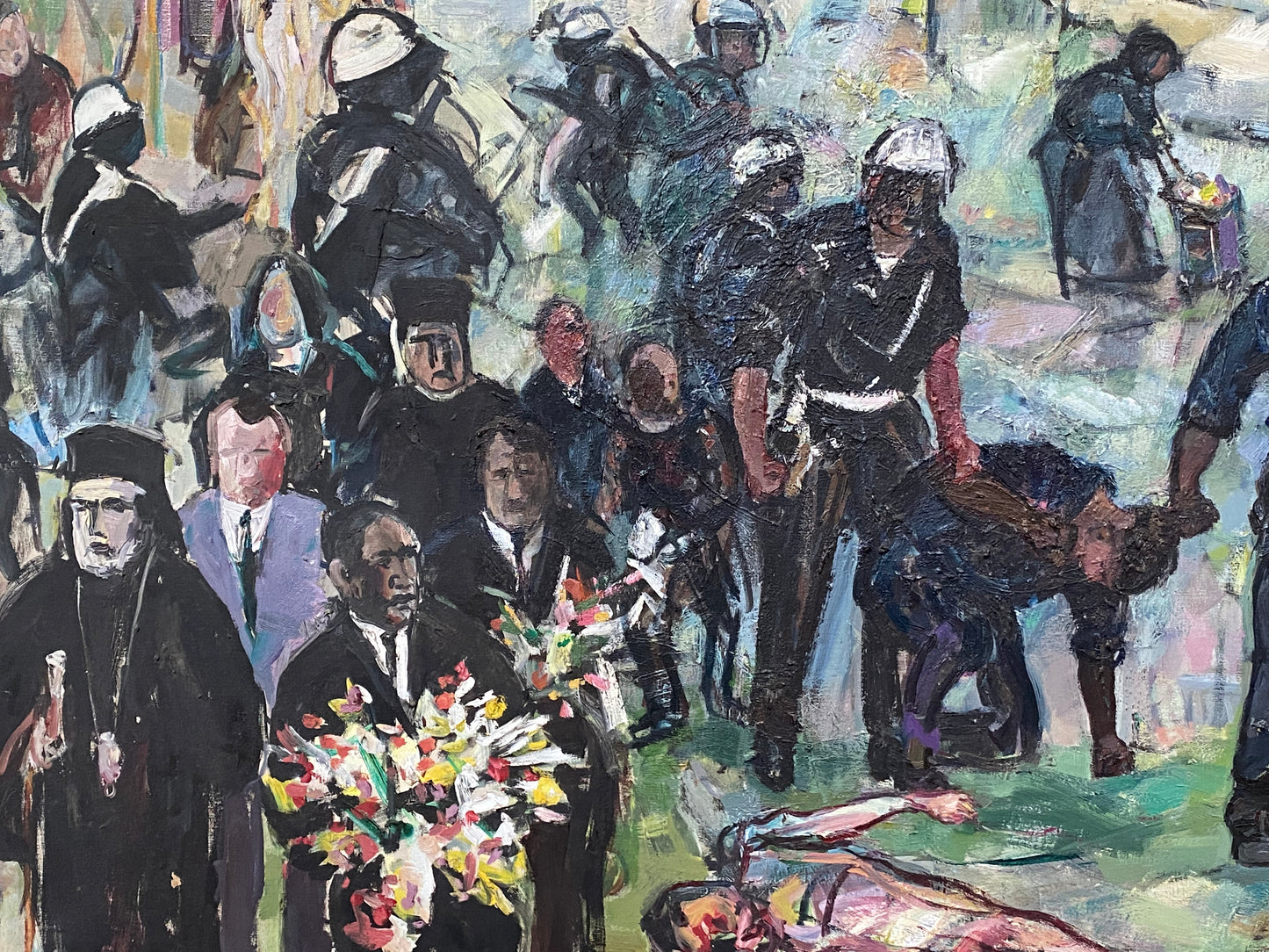

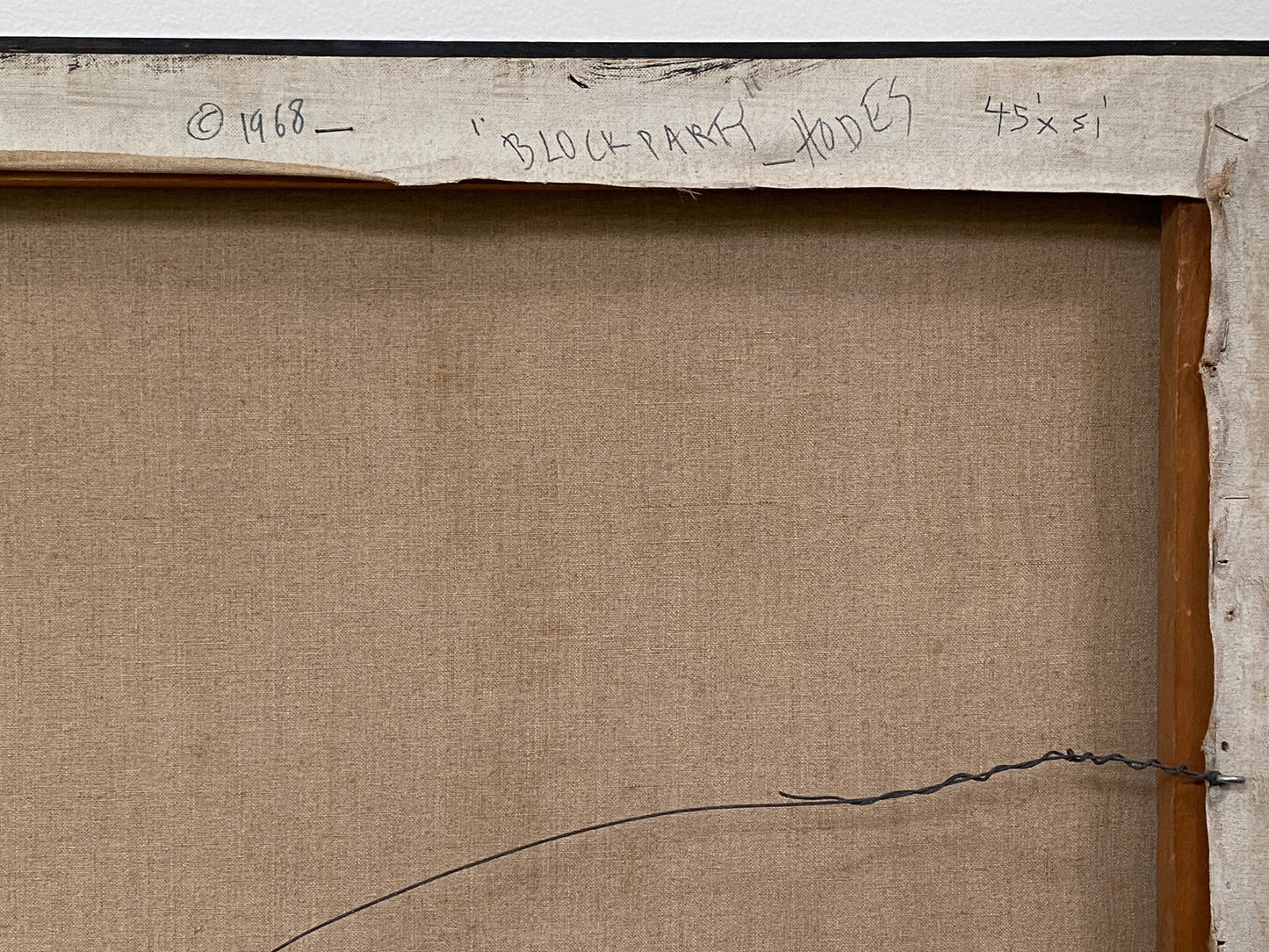

AN IMPORTANT LARGE-SCALE OIL ON CANVAS BY ACTIVIST / ARTIST, SUZANNE HODES, CREATED FRESH IN THE WAKE OF THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING JUNIOR AND DEPICTING THE FUNDERAL OF CIVIL RIGHTS MARTYR, JAMES REEB.

45 x 51 inches in original black strip frame; preserved in very good condition with some expected wear to frame.

WHO WAS JAMES REEB?

James Reeb was a white minister who became nationally known as a martyr to the civil rights cause when he was brutally burdered on 11 March 1965, in Selma, Alabama, after being attacked by a group of white men. Reeb had traveled to Selma to answer Martin Luther King’s call for clergy to support the nonviolent protest movement for voting rights there. Delivering Reeb’s eulogy, King called him “a shining example of manhood at its best” (King, 15 March 1965).

Reeb was born on New Year’s Day 1927, in Wichita, Kansas. After a tour of duty in the Army at the end of World War II, Reeb became a minister, graduating first from a Lutheran college in Minnesota, and then from Princeton Theological Seminary in June 1953. He then became assistant minister at All Souls Church in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1959. In September 1963 Reeb moved to Boston to work for the American Friends Service Committee. He bought a home in a “slum” neighborhood and enrolled his children in the local public schools, where many of the children were black.

On March 7, 1965, Reeb and his wife watched television news coverage of police attacking demonstrators in Selma as they attempted to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on what became known as “Bloody Sunday.” The following day, King sent out a call to clergy around the country to join him in Selma in a second attempt at a Selma to Montgomery March that Tuesday, March 9. Reeb heard about King’s request and was on a plane heading south that evening.

As Reeb was flying toward Selma, King was considering whether to disobey a pending court order against the Tuesday march to Montgomery. In the end he decided to march, telling the hundreds of clergy who had gathered at Brown’s Chapel, “I would rather die on the highways of Alabama, than make a butchery of my conscience” (King, 9 March 1965). King led the group of marchers to the far side of the bridge, then stopped and asked them to kneel and pray. After prayers, they rose and retreated back across the bridge to Brown’s Chapel, avoiding a violent confrontation with state troopers and skirting the issue of whether or not to obey the court order.

Several clergy decided to return home after this symbolic demonstration. Reeb, however, decided to stay in Selma until court permission could be obtained for a full-scale march, planned for the coming Thursday. That evening, Reeb and two other white Christians dined at an integrated restaurant. Afterward they were attacked by several white men and Reeb was clubbed on the head. Several hours elapsed before Reeb was admitted to a Birmingham hospital where doctors performed brain surgery. While Reeb was on his way to the hospital in Birmingham, King addressed a press conference lamenting the “cowardly” attack and asking all to pray for his protection (King, March 10, 1965). Reeb died two days later.

Reeb’s death provoked mourning throughout the country, and tens of thousands held vigils in his honor. President Lyndon B. Johnson called Reeb’s widow and father to express his condolences, and on March 15, he invoked Reeb’s memory when he delivered a draft of the Voting Rights Act to Congress. That same day King eulogized Reeb at a ceremony at Brown’s Chapel in Selma. “James Reeb,” King told the audience, “symbolizes the forces of good will in our nation. He demonstrated the conscience of the nation. He was an attorney for the defense of the innocent in the court of world opinion. He was a witness to the truth that men of different races and classes might live, eat, and work together as brothers” (King, March 15, 1965).

In April 1965 three white men were indicted for Reeb’s murder; they were acquitted that December. The Voting Rights Act was passed on August 6, 1965.

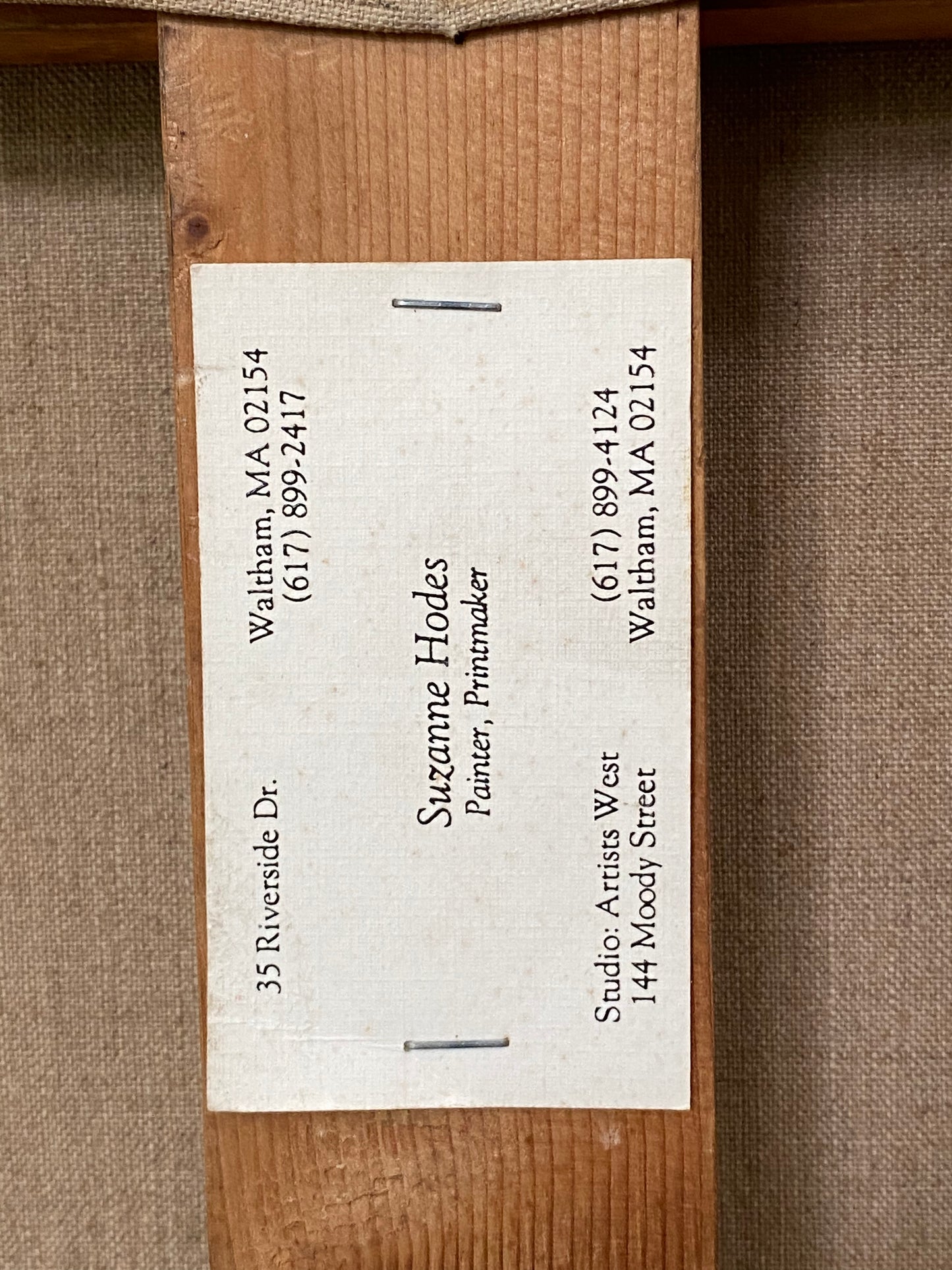

WHO WAS SUZANNE HODES?

Born in 1939, Suzanne Hodes was raised in New York City. While attending Radcliffe, she met Agnes Mongan, then Curator of Drawings at the Fogg Museum. The relationship blossomed and led to Hodes’ study for two summers at the Skowhegan School in Maine, and from there to study art at Brandeis. She studied under Arthur Polonsky, Mitchell Siporin, and most notably, intensive time spent with Oskar Kokoschka at his “School of Vision” in Salzburg.

Working with and under Kokoschka would play a significant role in her development. He was an artist and a writer; his aesthetic was message; he had something to say with his works. His intent to “message” was only heightened when he was forced to flee to London under Nazi occupation of Germany. His pre-War works were confiscated in Germany as degenerate and he spent the time in London creating works in protest of the Conflict. For Kokoschka, art had to say something or it forfeited its right to exist. It was a moral imperative.

Looking at the early works of Hodes, as represented by this important example, we can easily detect the abstract expressionism of New York that has been forced to speak, to say something, by being wed to Kokoschka’s activist art of cultural and philosophical resistance.

And these two streams, abstract expressionism and activism, met in her at precisely the right cultural moment, that is, the Civil Rights era. Hodes was deeply invested in the movement during her college years. As a white ally of the Civil Rights movement, James Reeb’s death in 1965 felt personally important. Then, when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, her own grief and despair found outlet in a flurry of paintings involving themes of social justice and civil rights.

The present, created immediately after the death of Dr. King, is among those pivotal works. It is expressive, energetic, . . . felt . . . but it is also legible, articulate . . . verbal protest.

Tucked into the lower left corner of the field, Martin Luther King Junior is shown attending the funeral of his friend, James Reeb. Hodes meaningfully places this out of center, though it is the evident historical moment of the painting, The death of Reeb was not isolated; it was but one event in an ongoing chaos of police brutality against black Americans, and against white Americans who supported black Americans. The violence of the painting menacingly swirls around even a black grandmother who is taking home her groceries. Even her innocent and mundane life is caught up in the chaos. And by the time we reach the upper right field, the scene is all but a military invasion; emptiness, remains of buildings, and faceless men with guns.

I spoke with the artist about this painting. She told me the painting was ultimately about Dr. King. His death brought forward a whole world of thoughts and feelings for her. There were the somber moments of other deaths, like James Reeb. There were the riots and police brutality, before and after his death. Also, the flowers, she said. They sit right in the center of that moment of darkness. They are brighter than everything else on the canvas. There is still hope, even in this painting. They are meaningful there, I think.

More recent, far less historically important works by Hodes sell at galleries for $8,000 - $12,000. This is a wonderful opportunity to purchase an early, historic work by a significant American artist. She is represented at major museums and in significant collections.

Please note there will be additional shipping costs which will be determined after purchase. Pick up or hand delivery may also be available.

Share