Specs Fine Books

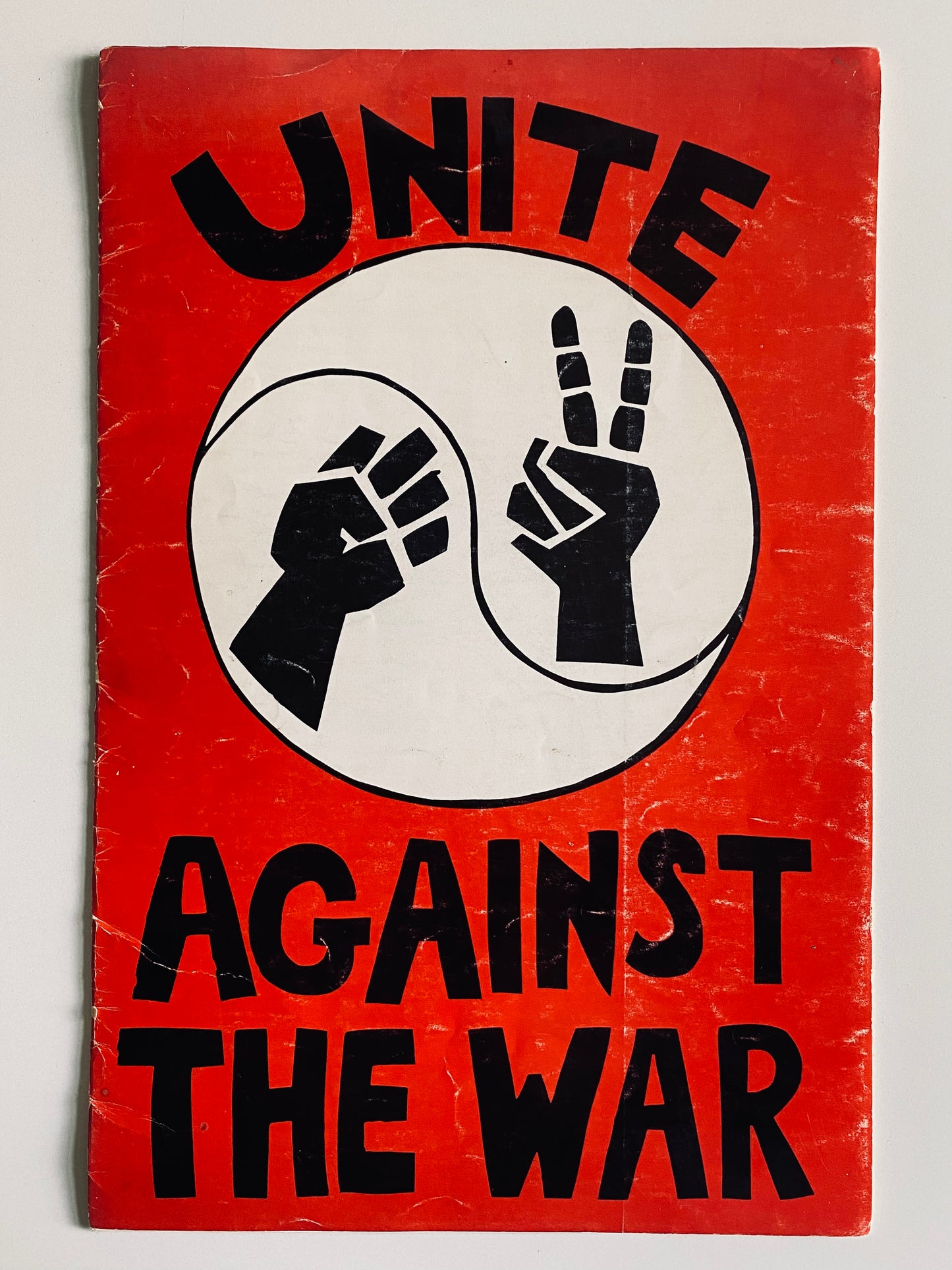

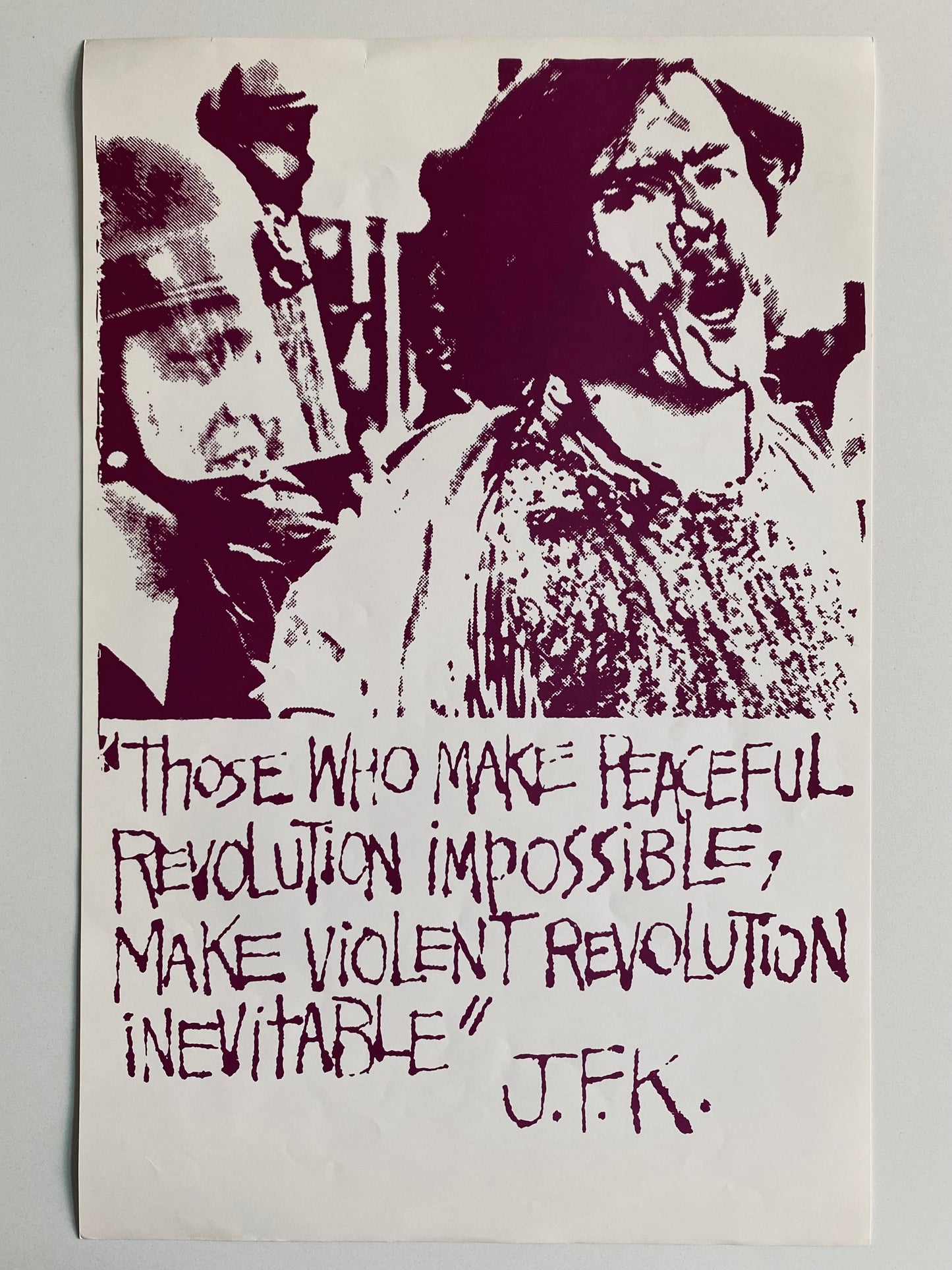

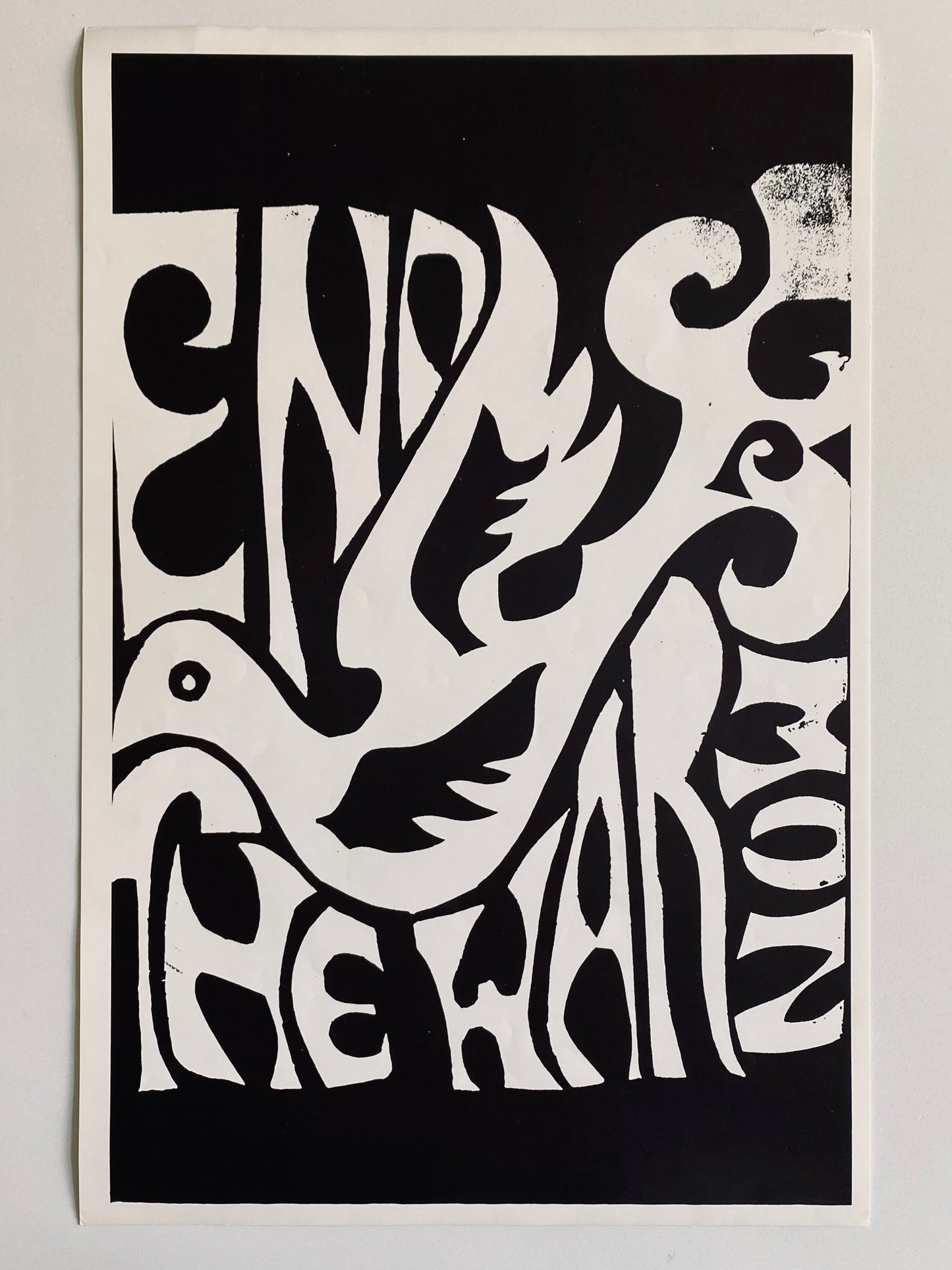

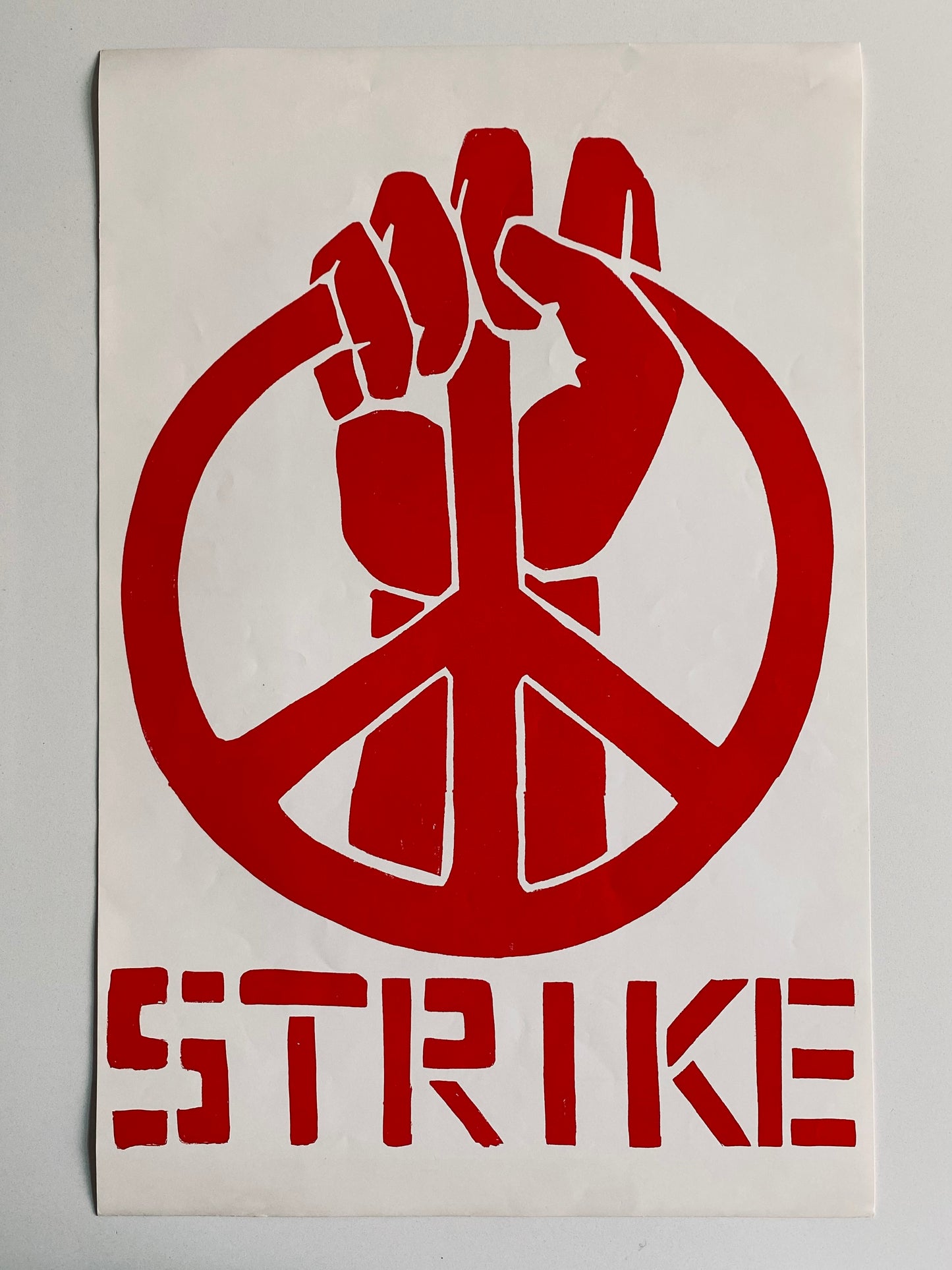

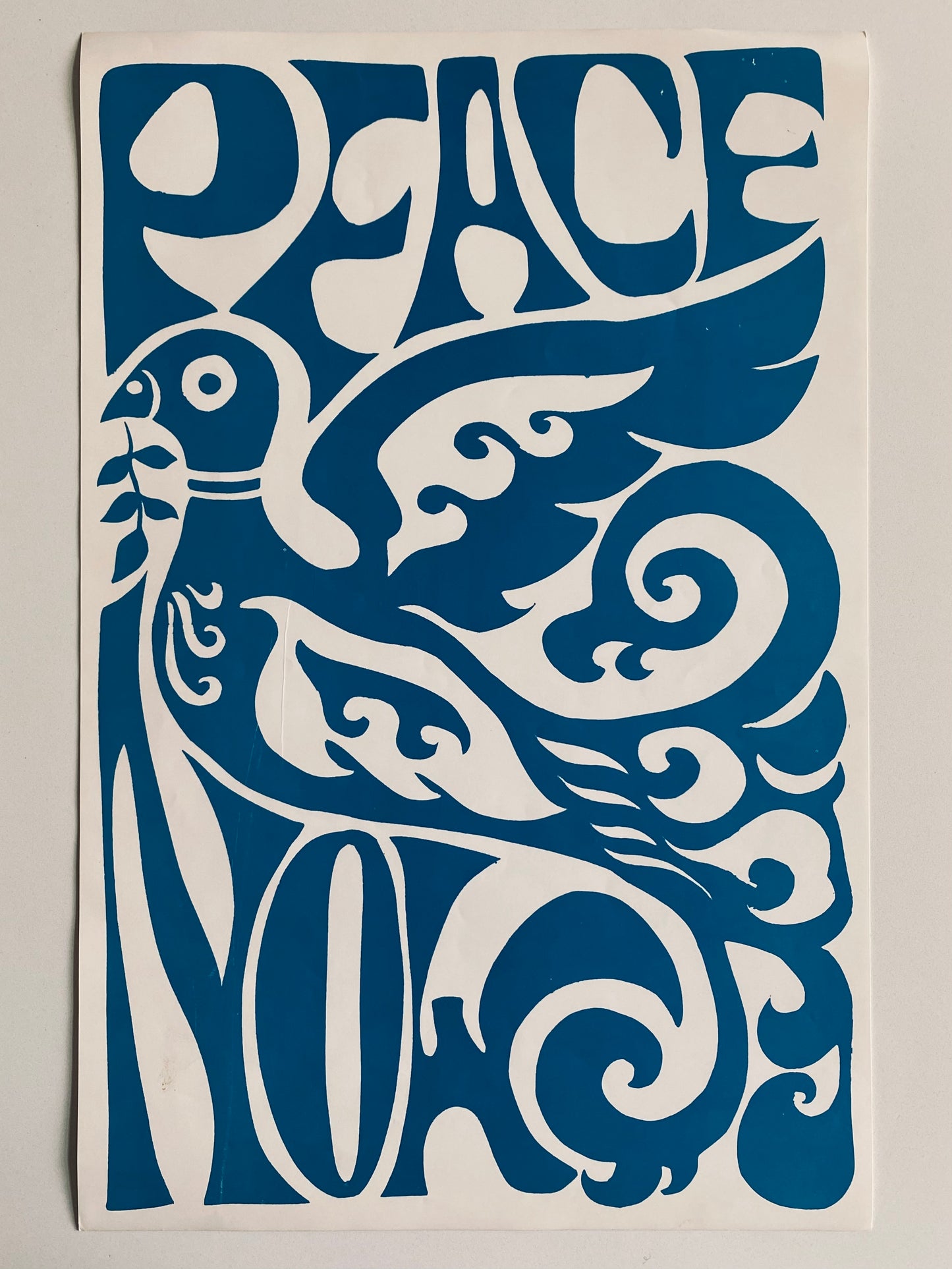

1970 VIETNAM WAR / CAMBODIA. Rare Group of X Peace Protest Posters Produced at Berkeley.

1970 VIETNAM WAR / CAMBODIA. Rare Group of X Peace Protest Posters Produced at Berkeley.

Couldn't load pickup availability

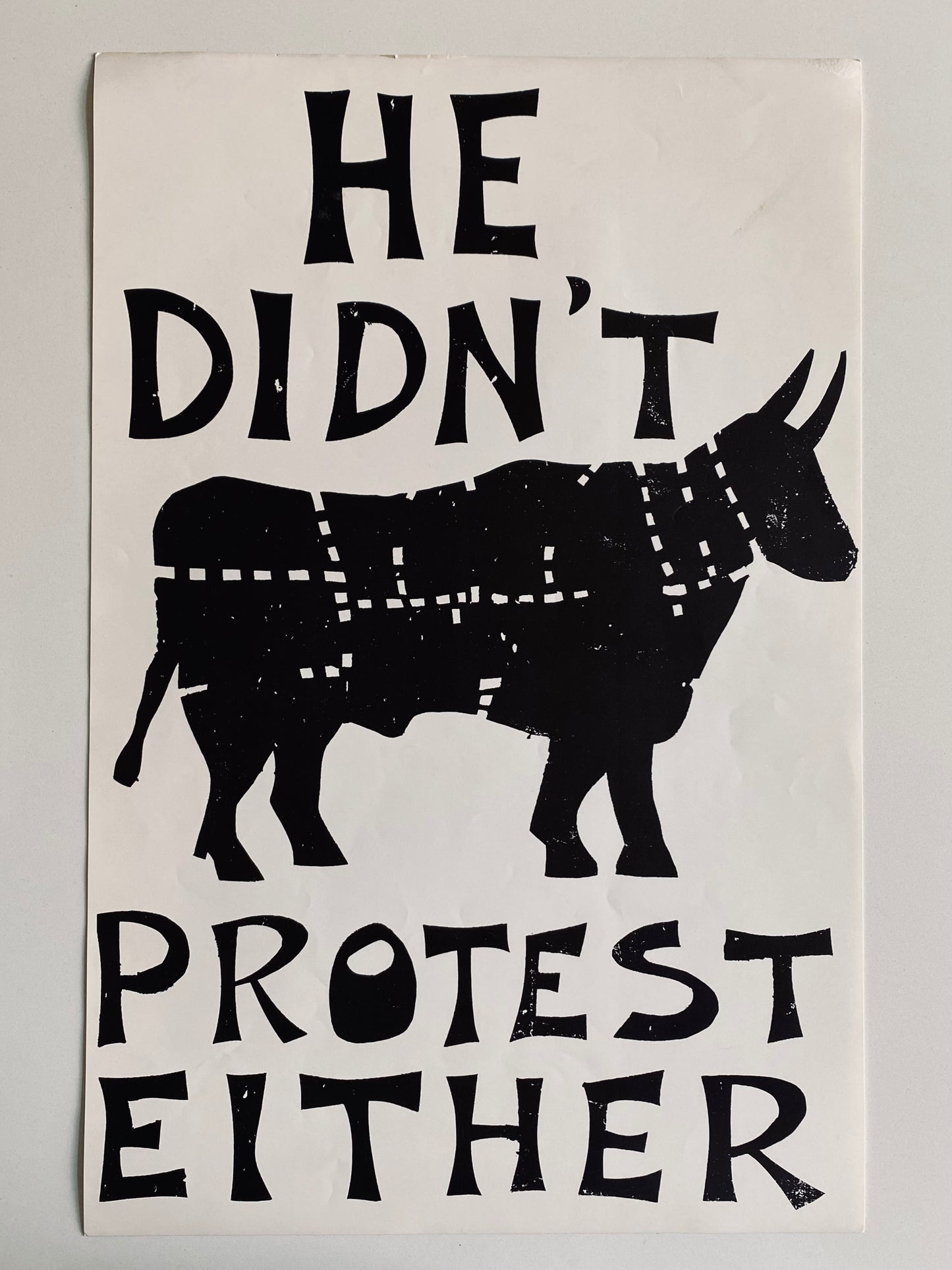

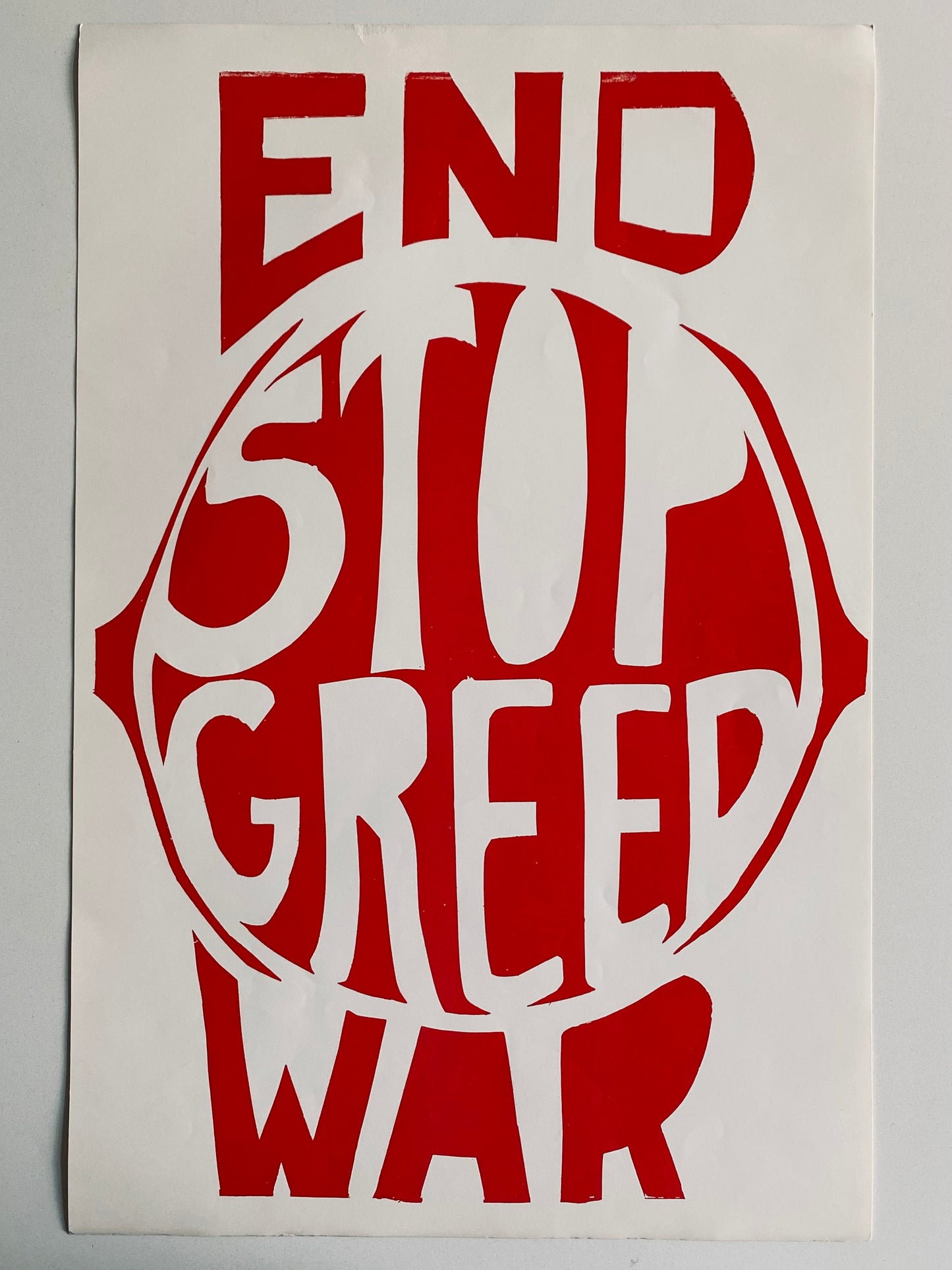

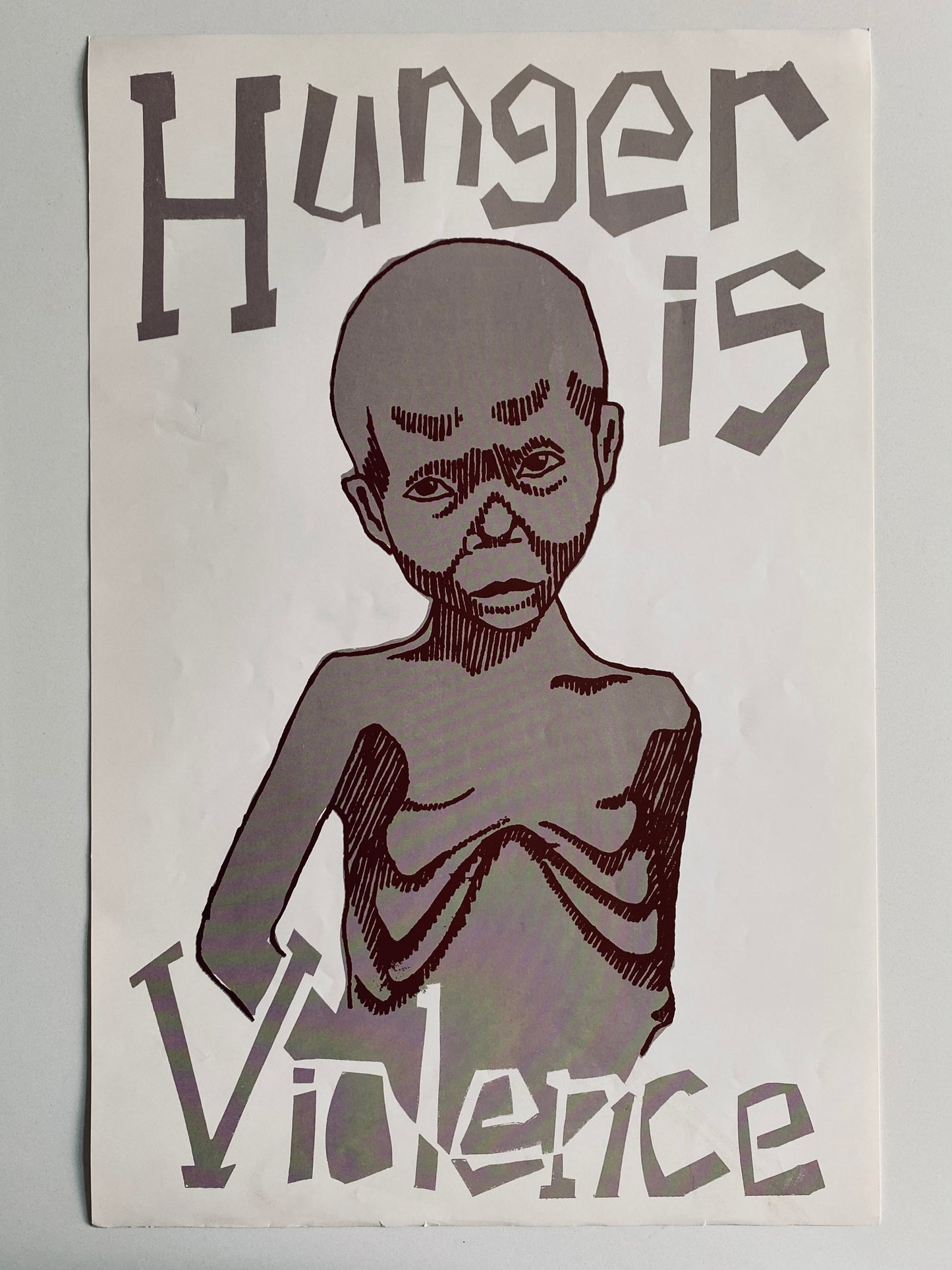

Very rare group of 11 lithographed peace protest posters issued for free reproduction and distribution to protest the War in Vietnam and Cambodia. Rare in any state, and rarely complete with the original folder.

Against the War. Posters from an Exhibition of May, 1970. Western Star Press. A Three Kings Production Box 248 Kentfield, California 94904. Students for Peace. 1970. First and Only Edition.

Very good condition with slight indent to head of folder and posters, tears at hinge of folder, some handling to folder. Contents likely never removed from the folder; aside from some light ripples, nearly as new.

Lorne Bair Rare Manuscripts & Ephemera offered an example of the present as part of his Berkeley Political Poster Workshop collection for $25,000.00.

Text from the interior rear flap:

Within this portfolio you will find some of the most powerful poster art being produced in the United States today. The posters are unsigned, however, because the artists conceive of themselves as contributors to a cause rather than as individual spokesmen. They are students in different schools in Northern California whose work was selected from an exhibition of posters that opened May 15, 1970, at the University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley, California.

The essay to introduce these posters was written by a scholar in the field of modern art. Professor Chipp has recently completed a study of the poster from the turn of the century to the present.

Students arranged this publication to help finance the peace movement. Additional copies can be ordered by writing. Western Star Press Box 24B Kentfield, California 94904

Copyright 1970 Students for Peace

Permission is granted to copy these posters or to reproduce them in any way that will assist in the cause of peace. Whoever uses them in any other way will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

Text from the inside front cover:

Posters for Peace.

The first half of May, 1970 may well be remembered as that unique moment when the youth and a large part of the public found itself working in a common cause. Never in recent times has there been such an outpouring of expressions for peace from citizens on all social levels, and these expressions found some of their earliest and most impassioned voices among the youth. While all the usual media of communication were employed, the movement of May, 1970 is unique in that it was the immediate cause of a flood of posters, many of which were of exceptional power.

Unlike the posters of earlier protest movements, these are general in theme and simple and powerful in style. The best of them meet the highest requirements for an effective social or political poster; text and image unified into a single concept and a clear and forceful theme. Since the overriding aim is the creation of an idea that is moving and not simply pleasing, there is little or any relationship to the advertising or the "art" poster, and their association with the advertising industry. On the contrary, these posters have the naked and sometimes brutal impact of a special news bulletin by an impassioned commentator. Since they were designed and printed by the students, often on silk screens they themselves had made and were rushed out to be posted while still wet, the activity as a whole is closer to that of a crusader (or to a revolutionary) than to that of an artist.

The student holding up a poster on a crowded sidewalk may have conceived and printed it himself only a few hours earlier. The immediacy and excitement of such a process is entirely in accord with contemporary modes of communication (and some currents of contemporary art), as well as with the temper of youthful protest.

Comparison with the French student revolution of May, 1968 is inevitable. The present movement, bursting forth on almost exactly the second anniversary of the former, also rapidly swept a nation. But, unlike in Paris, the 1970 movement addressed itself to the public and succeeded in carrying a large body of the public along with it. The principal means of addressing the public is now, as it was in 1968, by means of the poster. The two styles are remarkably similar in concept and may even be said to constitute a distinct style. With their sources in the realities of hard present-day social and political problems and strong convictions about them, they achieve a direct and forceful imagery that ignores conventional artistic poster concepts based on a desire to please or flatter. The viewer is not so much seduced as told, "This is the way things are, and this is what can be done about it." Since the message consists of opinions, it can best be conveyed in the simplest form - one or at most two primary colors arranged in simple or even crude fiat areas - like the statements themselves. Roughness of execution is a necessary result of haste and passion.

The contemporary poster, along with the film, has in the past few years emerged as a major means of communication. It is admirably suited to an age when our ideas are conveyed visually. The poster is immediate, direct, and may be repeated for emphasis. Its natural habitat is the street, where it addresses itself to everyman. The characteristics of the poster, not at all coincidentally, are also those of much of modern art: immediacy, unity of image and idea, and a simple but evocative motif stimulating a flood of associations.

During the first week of May, 1970, several poster workshops sprang up spontaneously in the San Francisco Bay Area Although manned by art and architecture students, their activities were independent of any classroom activities. Indeed, only a few of them had ever made a poster before. While some strong posters had been produced earlier in the year by the Women's Liberation Front in Berkeley, the great impetus came only with the peace movement in May. Students of the College of Environmental Design, led in organizing effective production and distribution, and were soon joined by art students and many others. Unlike the French students of 1968, their efforts were directed toward enlisting the support of the public, and they opened their workshops to it and provided posters to anyone who wished to use them.

In turn, the art history students arranged an exhibition that filled the University Art Gallery with work from the University of California, California College of Arts and Crafts, San Francisco Art Institute, Stanford, and others, to which were added posters from Mexico and Paris of May, 1968. Day by day new posters were added as they were produced. Thus some of the high excitement of the movement itself was conveyed in the gallery. A notable characteristic of the student poster movement is that during this burst of creative expression, which was accompanied by a sense that the message was heard, a great peace reigned on the campus.

Herschel B. Chipp

Professor of History of Art

Share