Specs Fine Books

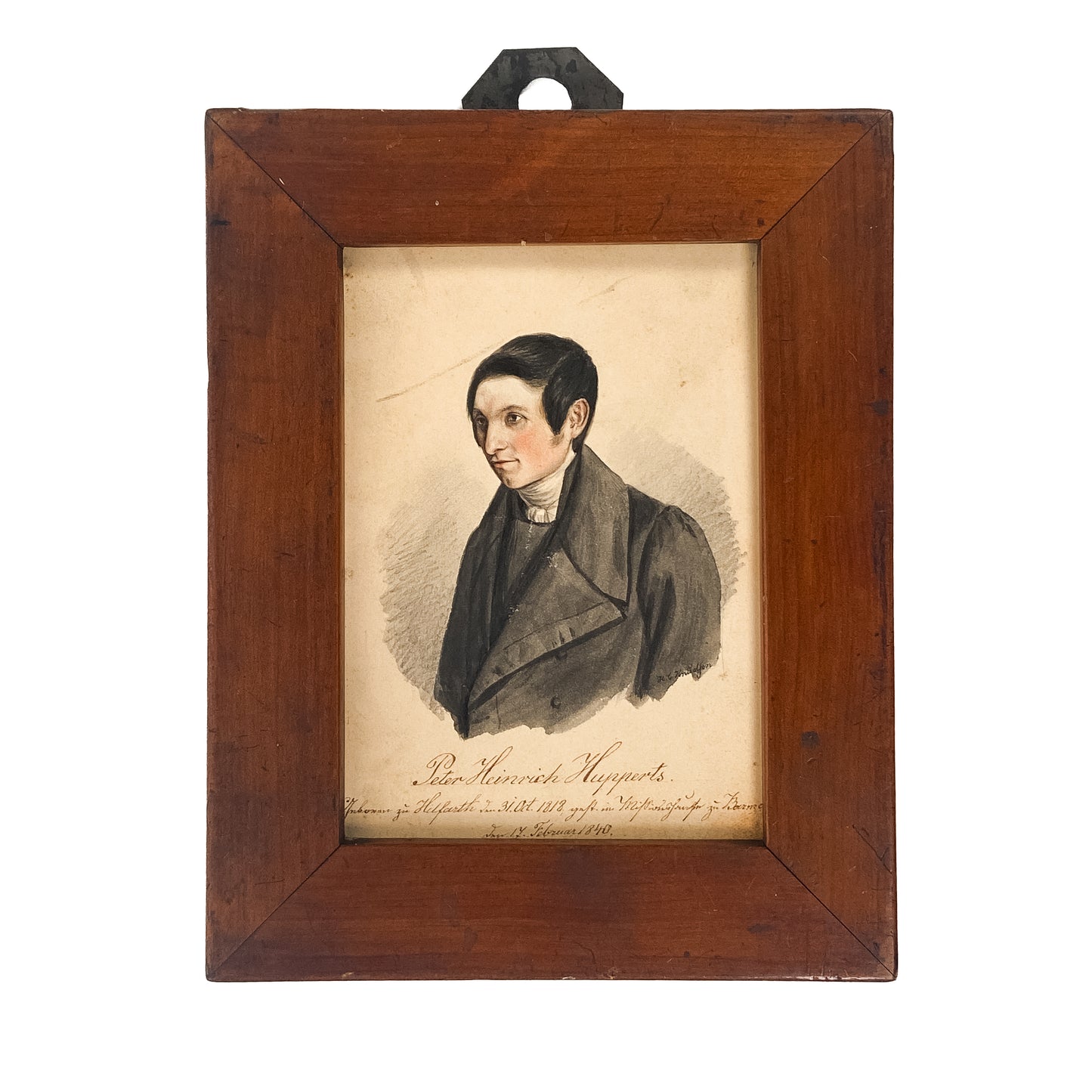

1840 PIONEER MISSIONARY-MARTYR BORNEO. Two Miniatures of J. G. Hupperts & P. H. Hupperts.

1840 PIONEER MISSIONARY-MARTYR BORNEO. Two Miniatures of J. G. Hupperts & P. H. Hupperts.

Couldn't load pickup availability

A really charming pair of superb miniatures on parchment depicting two missionary brothers who were pioneers of the Rhenish Missionary Society [RNS] in Borneo. Both executed by important missionary artist, H. C. Knudsen [see below].

The Hupperts.

The Rhenish Missionary Society was comprised of both Reformed and Lutheran missionaries, the Hupperts being among the Reformed branch. The RNS took over many of the missionary stations of the pietist Danish-Halle Mission [of August Hermann Francke, etc.]

The miniatures depict Johann Gottfried Hupperts [1812-1859]. Missionary at Palupetak Bintang and Bethabara, Borneo [1833-1853]. And Peter Heinrich Hupperts [1818-1840].

The Hupperts arrived in Borneo c.1835 to find a very difficult field indeed at the Pulopetak Mission. The area was controlled by the legendary Lion King. Locals were already violently opposed to the missionaries. Certainly, there was a lack of responsiveness to the demands of the Gospel. But there were pragmatic problems as well. Locals had been influenced by an influential Muslim population who wanted the route open for pilgrimage. And the community had more direct concerns about the treatment of slaves by the missionaries themselves.

Things did not go well. The Lion King and his people would agitate and rail against the missionaries and against the Gospel. If the historical reports are to be believed, the response of the missionaries was not ideal; they grew angry and shouted threats of eternal damnation.

By 1844, rumors abounded that the Lion King had hired an assassin to kill the Hupperts. That year, a jug of water was found in their home to have had a poison rag inserted. The Hupperts finally agreed to leave the region, but the Governor at Banjar urged the Hupperts to make one more attempt to share the Gospel with their formidable local King. This was the seventh formal proposal of the Gospel the missionaries made to him. It was unsuccessful, but the Hupperts remained.

The bright spot was the success of a local school they ran. In 1848 it had an enrollment of 100 pupils.

By the middle of 1859, the Banjar War was in full swing. Many missionaries, including their wives and children, were killed by the Dyaks [Dayaks]. Johann was killed as a part of these attacks. His wife and eight children escaped and were protected by the people of Gunong Lawak. The death of Hupperts remains controversial historically. He is seen by some as a martyr. Others note period records of alcohol abuse, anger problems, and violence against the locals and see Hupperts as an example of the Colonial privilege that led to the uprising in the first place.

Interestingly, Peter Heinrich is listed in none of the missionary records, but the miniature indicates that he was indeed a missionary in Borneo. By his age, we would suspect a brother of Johann's.

For more information, see Report of the British and Foreign Missionary Society [1853], pp.107-110; Missionary Register [1848], p.215; The Reformed Historical Magazine, Feb, 1895, pp.30-33.

Hans Christian Knudsen.

Both paintings executed and signed by Norwegian missionary and painter, Hans Christian Knudsen [1816-1863]. He was also a pioneer with the Rhenish Missionary Society and a notable scholar of Khoekhoe.

Born at Bergen, Norway he was trained as a painter and lithographer at the Bergen Academy of Art and Design. He joined the Rhenish Missionary Society in Elberfeld-Barmen in 1836, and upon completing his training at the missionary institute was dispatched in 1841 to South-West Africa to further the work of Heinrich Schmelen [1776–1848] who had been based at what is now Bethanie, Namibia.

Knudsen took his post in Bethanie in November 1842. He took to missionary work naturally and began to assist the locals by helping them codify their oral law to prevent impulsive and revenge-driven executions. The resulting code was adopted as tribal law in October 1848. Other tribes adopted the same code with amendments. The core of the legal corpus he helped formulate remains in force today and provided a foundation for agreement among the subtribes of the region.

Knudsen traveled through the tribal territories around Bethanie and Berseba, recording his observations in diaries and reports. He also drew and painted portraits of distinguished chieftains, scenes of village life, and ordinary Herero in Windhoek. He was the first European artist based in South-West Africa. His works were published in the mission magazine and are currently displayed in the mission archives. The only works of his remaining in Southern Africa are two portraits of Khoikhoi at Stellenbosch University.

His diaries are likewise preserved and attest to his serious attention to the language and customs of the Nama, Damara (Herero), and San peoples. His findings conflict with those of the explorer Sir James Edward Alexander, especially in the 1844-1845 entries where he claims the Nama to be descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

In 1849, he returned to Norway for respite and to raise funds. When he found his way back to Bethanie in 1849, most of his congregation had abandoned Christianity and joined the raids of Jonker Afrikaner against the Herero. Boycotting the raids in protest, he was banished by the chief of Bethanie.

Bitterly disappointed, Knudsen roamed around missions in the Northern Cape, ending up in Tulbagh in 1852. Struggling to adapt and cope with his wife becoming mentally ill, he left the ministry in 1854 and returned to Norway. His wife died in an asylum and he made a meager living as an itinerant preacher dying at Hattfjelldal, Norway. His two sons were adopted and raised by family members.

Knudsen's first publication was Nama A.B.Z. kannis [Cape Town, 1845], a short book of prayers and readings with a glossary, English translation, and part of the catechism, the Ten Commandments, and other parts of the Holy Scriptures. Around the same time, he published an alphabet of sorts in the Nama language. Copies of both appear in the Grey collection in the National Library of South Africa Cape Town campus, complete with Knudsen's handwritten notes. The same collection includes his handwritten Südafrica: Das Hottentot-Volk: Notizzen ("South Africa: The Khoikhoi: Notes"), Stoff zu einer Grammatik in der Namaquasprache ("Fundamentals of Grammar in the Nama Language"), and Namaquasprache. These cover the geography and ethnography of Great Namaqualand as well as Khoekhoe syntax.

Knudsen's translation of the Gospel of Luke and the two aforementioned Cape Town publications were key sources for RMS Inspector J.C. Wallmann's Vocabular der Namaqua Sprache nebst einem Abrise der Formenlehre derselben ("Vocabulary of the Nama Language and Fundamentals of its Grammar," Barmen, 1854). His Gospel of Luke in Khoekhoe was published in Cape Town with some hymns in 1846 after a few productive years of learning the language with the help of two Nama translators. Though slightly proofread on spelling from the earlier publications, Wallmann's copy was rendered so meticulously that it was virtually free of printing errors, and Wilhelm Bleek described it in 1858 as "so far the best and most reliable source on [Khoekhoe]". Though somewhat rigid, it rendered idioms accurately.

Share